Organizing against Slavery

More radical still was the movement in the 1830s to abolish the sin of slavery. The abolitionist movement had its roots in Great Britain in the late 1700s. (See “Beyond America’s Borders.”) Previously, the American Colonization Society, founded in 1817 by Maryland and Virginia planters, promoted gradual individual emancipation of slaves followed by colonization in Africa. By the early 1820s, several thousand ex-

Around 1830, northern challenges to slavery intensified, beginning in free black communities. In 1829, a Boston printer named David Walker published An Appeal . . .

The Liberator, founded in 1831 in Boston, took antislavery agitation to new heights. Its founder and editor, William Lloyd Garrison, advocated immediate abolition: “On this subject, I do not wish to think, or speak, or write, with moderation. No! No! Tell a man whose house is on fire to give a moderate alarm; tell him to moderately rescue his wife from the hands of the ravisher; tell the mother to gradually extricate her babe from the fire into which it has fallen—

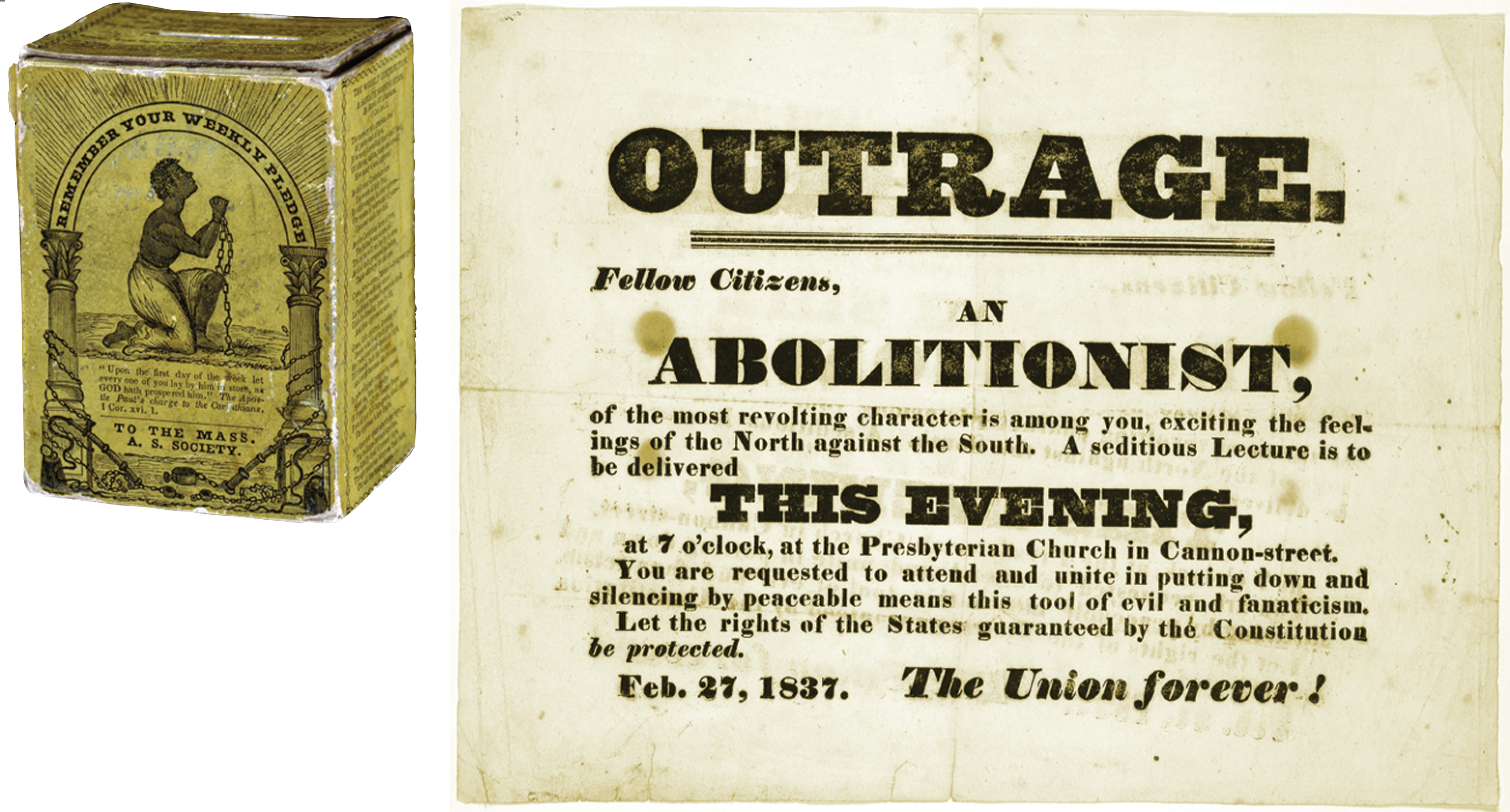

Similar groups were organized in Philadelphia and New York in 1833. Soon a dozen antislavery newspapers and scores of antislavery lecturers were spreading the word and inspiring the formation of new local societies, which numbered thirteen hundred by 1837. Confined entirely to the North, their membership totaled a quarter of a million men and women.

Many white northerners, even those who opposed slavery, were not prepared to embrace the abolitionist call for emancipation. From 1834 to 1838, there were more than a hundred eruptions of serious mob violence against abolitionists and free blacks. On one occasion, antislavery headquarters in Philadelphia and a black church and orphanage were burned to the ground. In another incident, Illinois abolitionist editor Elijah Lovejoy was killed by a rioting crowd attempting to destroy his printing press. When the Grimké sisters lectured in 1837 (see the introduction to this chapter), some authorities tried to intimidate them and deny them meeting space. The following year, rocks shattered windows when Angelina Grimké gave a speech at a female antislavery convention in Philadelphia. After the women vacated the building, a mob burned the building to the ground.

Despite these dangers, large numbers of northern women played a prominent role in abolition. They formed women’s auxiliaries and held fairs to sell handmade crafts to support male lecturers in the field. They circulated antislavery petitions, presented to the U.S. Congress with tens of thousands of signatures. At first women’s petitions were framed as respectful memorials to Congress about the evils of slavery, but soon they demanded political action to end slavery in the District of Columbia, under Congress’s jurisdiction. By such fervent tactics, antislavery women asserted their claim to be heard on political issues independently of their husbands and fathers.

Garrison particularly welcomed women’s activity, despite the potential for danger. The 1837 Massachusetts speaking tour of the Grimké sisters brought out respectful audiences of thousands but also drew intimidation from some quarters. The state leaders of the Congregational Church in Massachusetts banned the sisters from speaking in their churches. While a modest woman deserved deference and protection, church leaders said, immodest women presumptuously instructing men in public forfeited feminine privileges. “When she assumes the place and tone of man as a public reformer, our care and protection of her seem unnecessary; we put ourselves in self-

By the late 1830s, the cause of abolition divided the nation as no other issue did. Even among abolitionists, significant divisions emerged. The Grimké sisters, radicalized by the public reaction to their speaking tour, began to write and speak about woman’s rights. Angelina Grimké compared the silencing of women to the silencing of slaves: “The denial of our duty to act, is a bold denial of our right to act; and if we have no right to act, then may we well be termed ‘the white slaves of the North’—for, like our brethren in bonds, we must seal our lips in silence and despair.” The Grimkés were opposed by moderate abolitionists who were unwilling to mix the new and controversial issue of woman’s rights with their first cause, the rights of blacks.

The many men and women active in reform movements in the 1830s found their initial inspiration in evangelical Protestantism’s dual message: Salvation was open to all, and society needed to be perfected. Their activist mentality squared well with the interventionist tendencies of the Whig Party forming in opposition to Andrew Jackson’s Democrats.

REVIEW How did evangelical Protestantism contribute to the social reform movements of the 1830s?