Beyond America’s Borders: “Transatlantic Abolition”

A bolitionism blossomed in the United States in the 1830s, but its roots stretched back to the 1780s in Britain and America. Developments in both countries led to a transatlantic antislavery movement with shared ideas, strategies, activists, songs, and, eventually, victories.

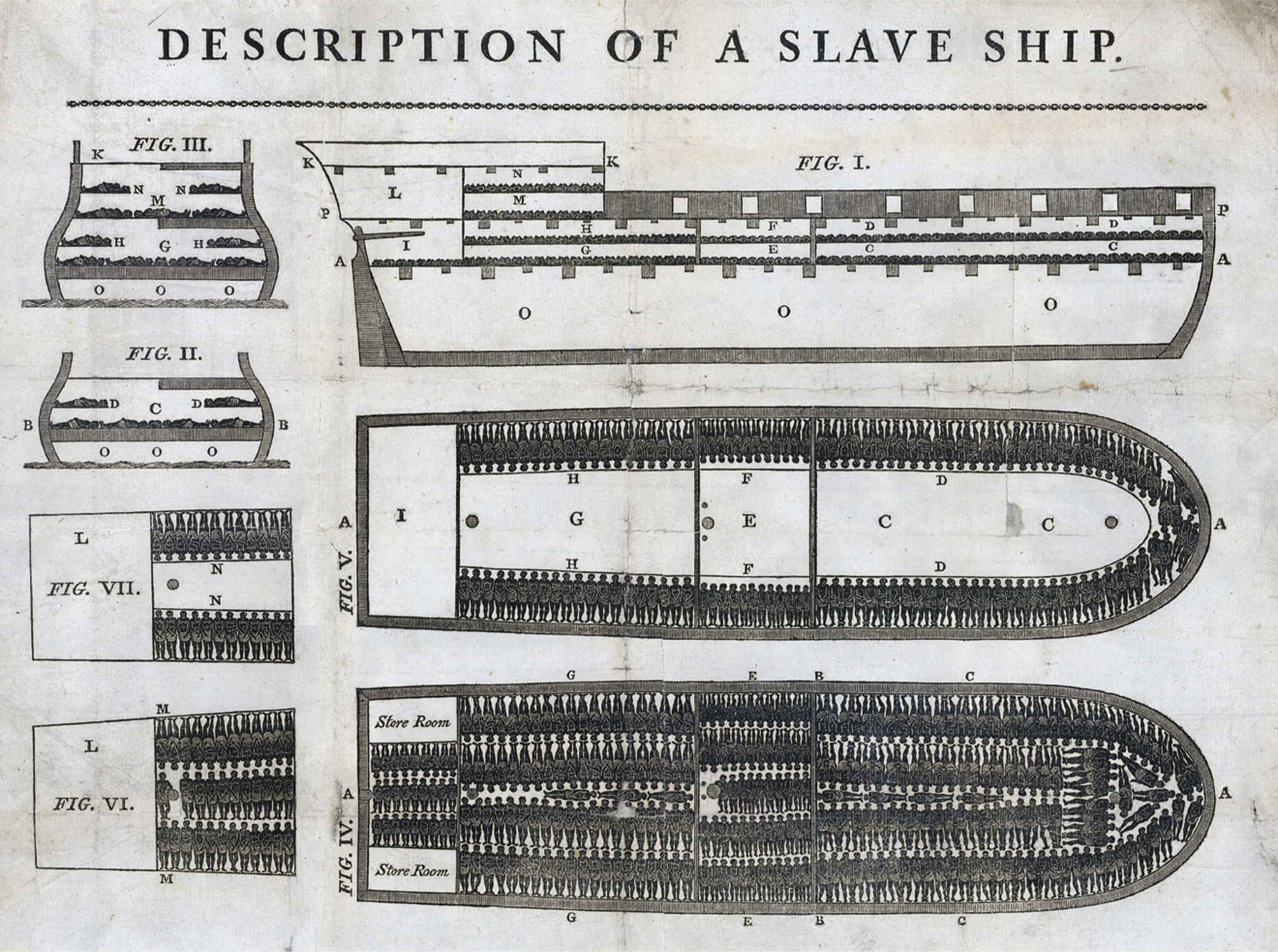

An important source of antislavery sentiment derived from the Quaker religion, with its deep convictions regarding human equality. But moral sentiment alone does not make a political movement. English Quakers, customarily an apolitical group, awoke to sudden antislavery zeal in 1783, triggered in part by the loss of the imperial war for America and the debate it spurred about citizenship and slavery. The end of the war also brought a delegation of Philadelphia Quakers to meet with the London group, and an immediate result was the first petition requesting that Parliament abolish the slave trade.

The English Quakers, now joined by a scattering of evangelical Anglicans and Methodists, formed the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade in 1787 and in just five years became a force to be reckoned with. They amassed thousands of signatures on petitions to Parliament. They organized a boycott of slave-

Meanwhile, Pennsylvania Quakers in 1784 launched their own Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, which worked to end slavery in that state and petitioned the confederation congress—

The antislavery movement also took root in France, with the founding of the Société des Amis des Noirs (Society of the Friends of Blacks) in 1788. Inspired by Quaker groups in London and Philadelphia, the Société sent petitions to the French National Assembly. All three antislavery groups, in close communication, agreed that ending the slave trade was the critical first step in abolishing slavery. That goal was achieved once the revolution of liberté and égalité came to France; a 1794 decree of the National Assembly freed all French colonial slaves and termed them citizens.

Success came more slowly in Britain and America. In 1807, Parliament finally made it illegal for British ships to transport Africans into slavery. A year later, the United States also banned the international slave trade. The rapid natural increase of the African American population made passage of this law relatively easy. Older slave states along the coast supported the ban because it actually increased the value of their native-

British antislavery forces took a new tack in the 1820s, when women became active and pushed beyond the ban on trade. Quaker widow Elizabeth Heyrick authored Immediate Not Gradual Abolition in 1824, prompting the formation of scores of all-

The success of the British movement generated even greater transatlantic communication. In 1840, British and American abolitionists came together in full force at the World Anti-

America in a Global Context

- What were some of the tactics that British abolitionists used to advance their cause?

- What factors help explain why the emancipation of slaves came earliest in France, and then four decades later in Britain and seven decades later in the United States?

Connect to the Big Idea

What parts of American abolitionism owed their origins and inspiration to European models? Do you think there were aspects of American abolitionism that would have emerged even without any European models? Why or why not?