Improvements in Transportation

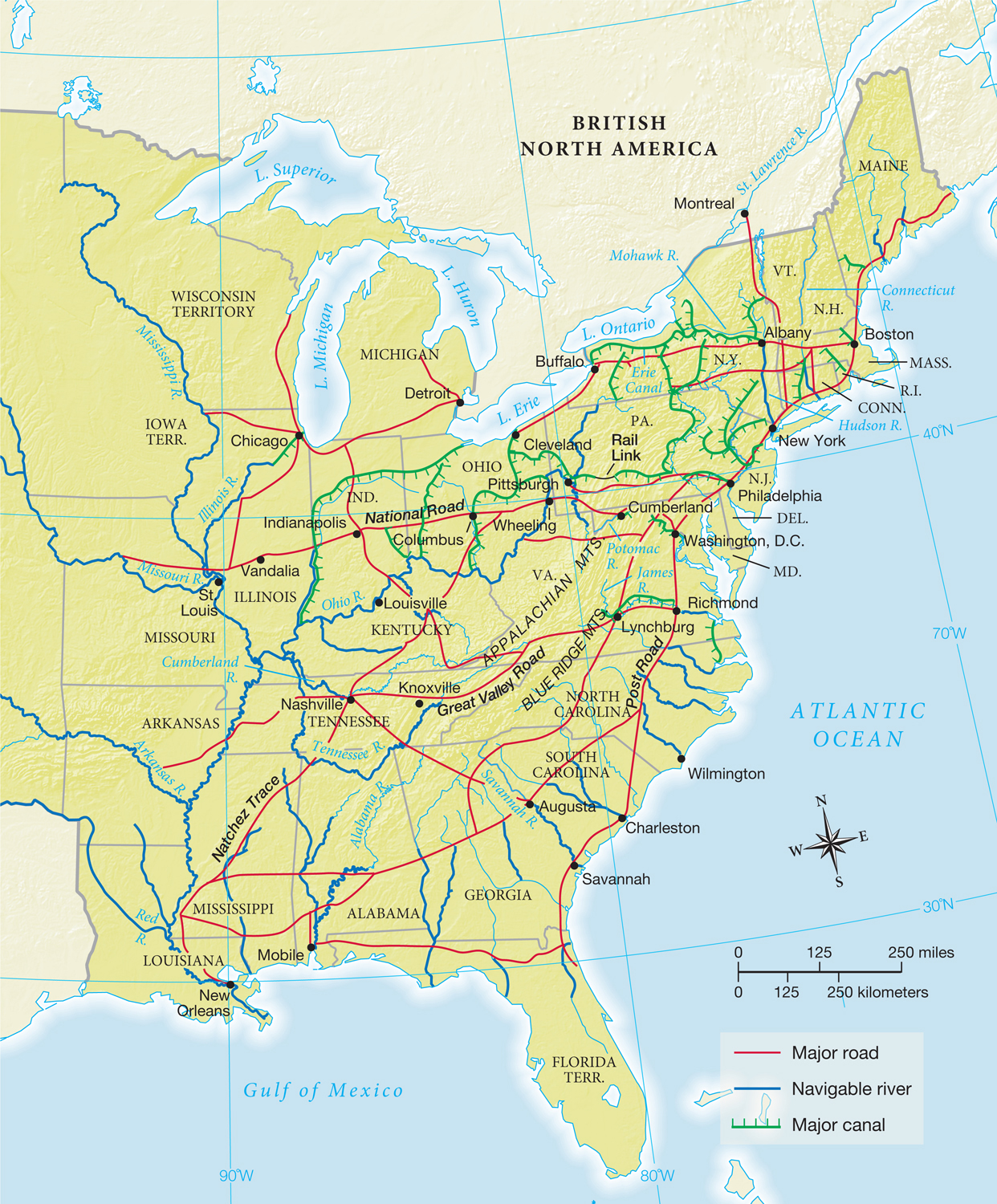

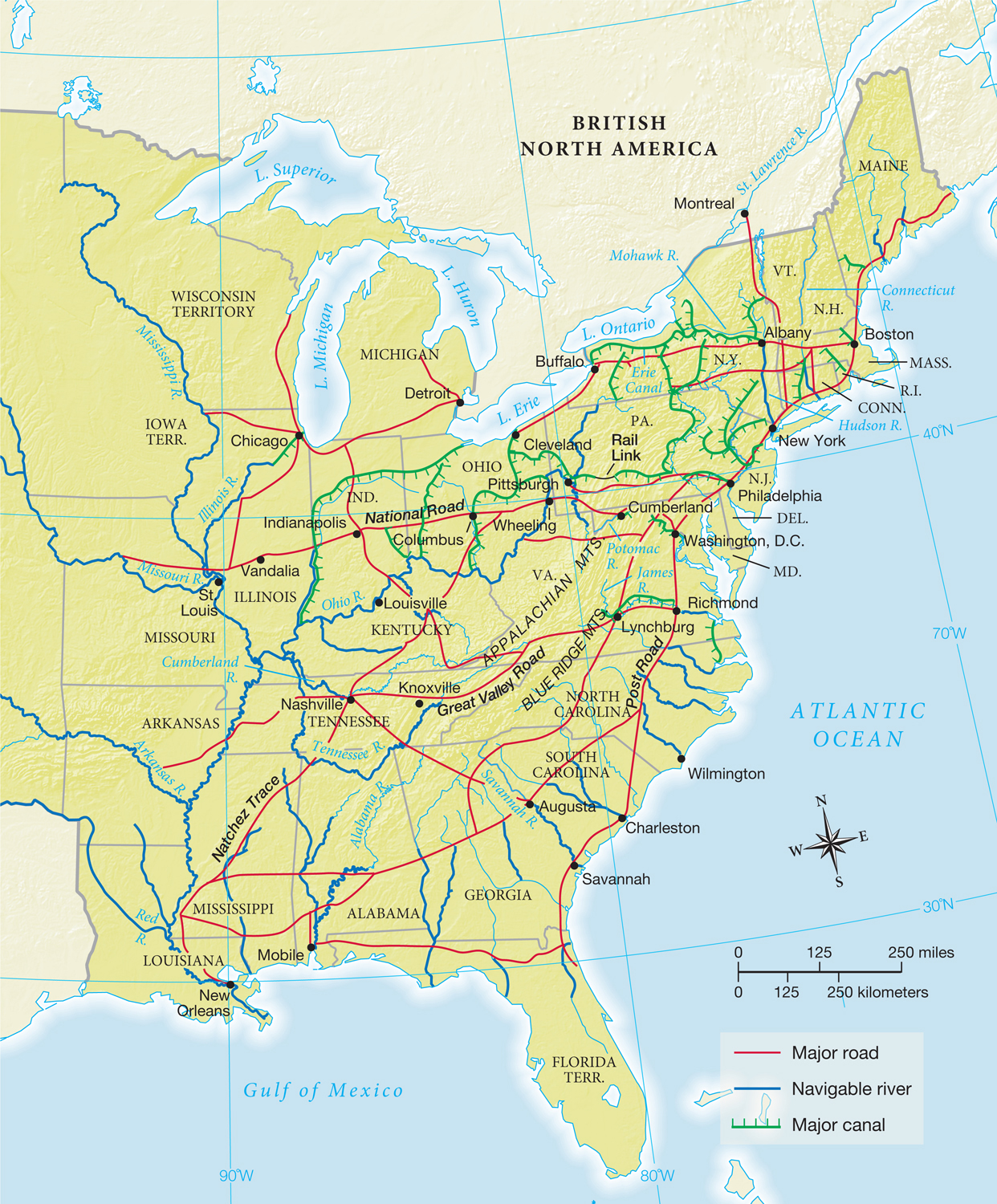

Before 1815, transportation in the United States was slow and expensive; it cost as much to ship a crate over thirty miles of domestic roads as it did to send it across the Atlantic Ocean. A stagecoach trip from Boston to New York took four days. But between 1815 and 1840, networks of roads, canals, steamboats, and finally railroads dramatically raised the speed and lowered the cost of travel (Map 11.1).

MAP ACTIVITY Map 11.1 Routes of Transportation in 1840 Transportation advances cut travel times significantly. On the Erie Canal, goods and people could move from New York City to Buffalo in four days, a two-week trip by road. Steamboats cut travel time from New York to New Orleans from four weeks by road to less than two weeks by river. READING THE MAP: In what parts of the country were canals built most extensively? Were most of them within a single state’s borders, or did they encourage interstate travel and shipping? CONNECTIONS: What impact did the Erie Canal have on the development of New York City? How did improvements in transportation affect urbanization in other parts of the country?

Improved transportation moved goods into wider markets. It moved passengers, too, allowing young people as well as adults to take up new employment in cities or factory towns. Transportation also facilitated the flow of political information via the U.S. mail with its bargain postal rates for newspapers, periodicals, and books. Enhanced public transport was expensive and produced uneven economic benefits, so presidents from Jefferson to Monroe were reluctant to fund it with federal dollars. Instead, private investors pooled resources and chartered transport companies, receiving significant subsidies and monopoly rights from state governments. Turnpike and roadway mileage increased dramatically after 1815, reducing shipping costs. Stagecoach companies proliferated, and travel time on main routes was cut in half.

Water travel was similarly transformed. In 1807, Robert Fulton’s steam-propelled boat, the Clermont, churned up the Hudson River from New York City to Albany, touching off a steamboat craze on eastern rivers and the Great Lakes. By the early 1830s, more than seven hundred steamboats were in operation on the Ohio and Mississippi rivers.

Steamboats were not benign advances, however. The urgency to cut travel time led to over-stoked furnaces, sudden boiler explosions, and terrible mass fatalities. An investigation of an accident near Cincinnati in 1838, in which 150 passengers were killed, charged: “Such disasters have their foundation in the present mammoth evil of our country, an inordinate love of gain. We are not satisfied with getting rich, but we must get rich in a day. We are not satisfied with traveling at a speed of ten miles an hour, but we must fly.” By the mid 1830s, nearly three thousand Americans had been killed in steamboat accidents, leading to the first federal attempt to regulate safety on vessels used for interstate commerce. Environment costs were also large: Steamboats had to load fuel—“wood up”—every twenty miles or so, resulting in mass deforestation. By the 1830s, the banks of many main rivers were denuded of trees, and forests miles back from the rivers fell to the ax. The smoke from wood-burning steamboats created America’s first significant air pollution.

Canals were another major innovation of the transportation revolution. Canal boats powered by mules moved slowly—less than five miles per hour—but the low-friction water enabled one mule to pull a fifty-ton barge. Several states commenced major government-sponsored canal enterprises, the most impressive being the Erie Canal, finished in 1825, covering 350 miles between Albany and Buffalo and linking the port of New York City with the entire Great Lakes region. Wheat and flour moved east, household goods and tools moved west, and passengers went in both directions. By the 1830s, the cost of shipping by canal fell to less than one-tenth of the cost of overland transport, and New York City quickly blossomed into the premier commercial city in the United States.

The Erie Canal at Lockport The Erie Canal, completed in 1825, was impressive not only for its length of 350 miles but also for its elevation, requiring the construction of eighty-three locks. The biggest engineering challenge came at Lockport, twenty miles northeast of Buffalo, where the canal traversed a steep slate escarpment. Work crews—mostly immigrant Irishmen—used gunpowder and grueling physical labor to blast the deep artificial gorge shown here. Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Rush Rhees Library, University of Rochester.

In the 1830s, private railroad companies heavily subsidized by state legislatures began to give canals competition. The nation’s first railroad, the Baltimore and Ohio, laid thirteen miles of track in 1829, and by 1840, three thousand more miles of track materialized nationwide. Rail lines in the 1830s were generally short, on the order of twenty to one hundred miles. They did not yet provide an efficient distribution system for goods, but passengers flocked to experience the marvelous speeds of fifteen to twenty miles per hour. Railroads and other advances in transportation served to unify the country culturally and economically.