The Plantation Economy

As important as slavery was in unifying white Southerners, only about a quarter of the white population lived in slaveholding families. Most slaveholders owned fewer than five slaves. Only about 12 percent of slaveholders owned twenty or more, the number of slaves that historians consider necessary to distinguish a planter from a farmer. Despite their small numbers, planters dominated the southern economy. In 1860, 52 percent of the South’s slaves lived and worked on plantations. Plantation slaves produced more than 75 percent of the South’s export crops, the backbone of the region’s economy. While slavery was dying elsewhere in the New World (only Brazil and Cuba still defended slavery at midcentury), slave plantations increasingly dominated southern agriculture.

The South’s major cash crops—

But by the nineteenth century, cotton reigned as king of the South’s plantation crops. Cotton became commercially significant in the 1790s after the invention of a new cotton gin by Eli Whitney (see “Agriculture, Transportation, and Banking” in chapter 9). Cotton was relatively easy to grow and took little capital to get started—

Plantation slavery also enriched the nation. By 1840, cotton accounted for more than 60 percent of American exports. Most of the cotton was shipped to Great Britain, the world’s largest manufacturer of cotton textiles. Much of the profit from the sale of cotton overseas returned to planters, but some went to northern middlemen who bought, sold, insured, warehoused, and shipped cotton to the mills in Great Britain. As one New York merchant observed, “Cotton has enriched all through whose hands it has passed.” As middlemen invested their profits in the booming northern economy, industrial development received a burst of much-

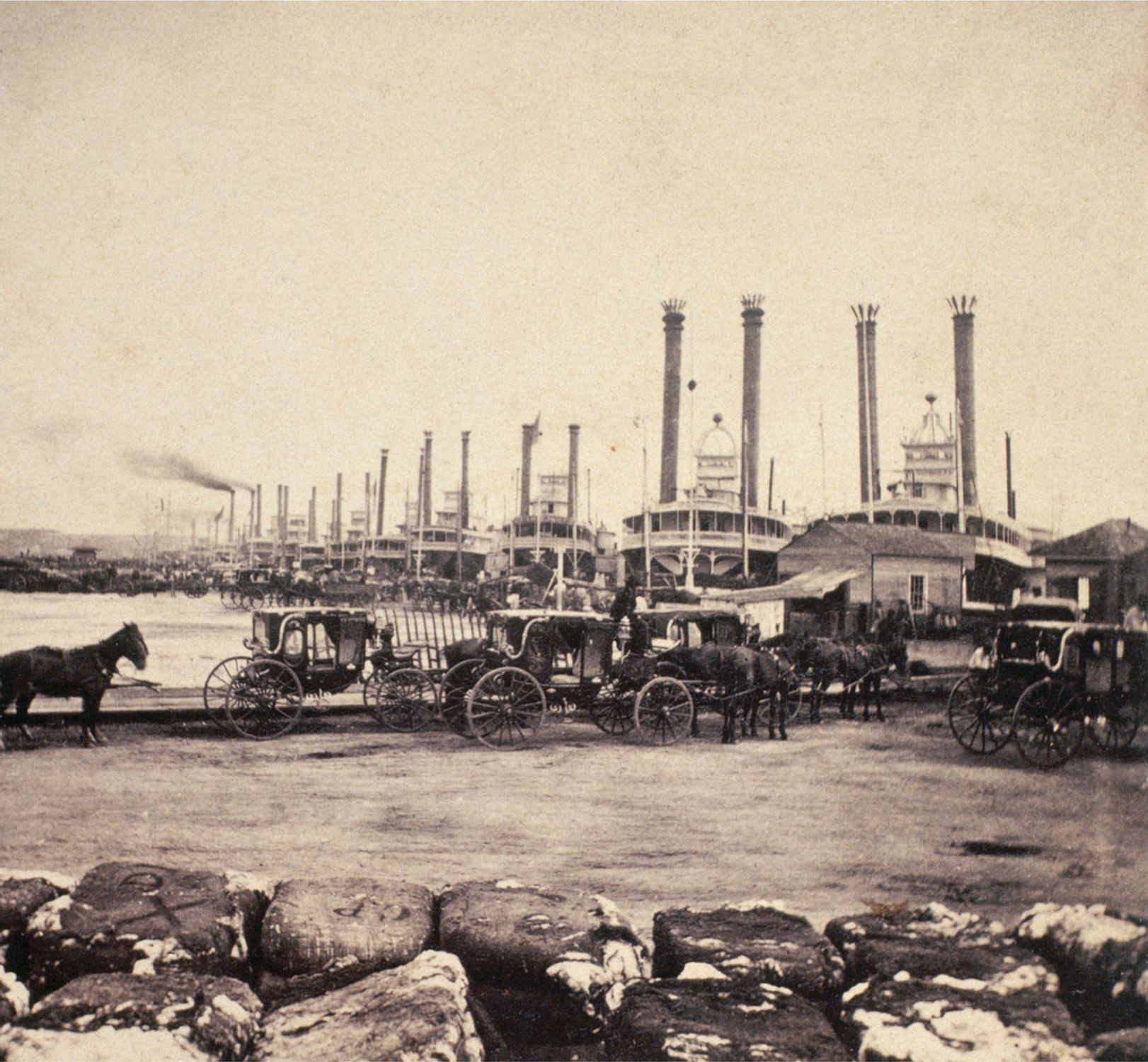

The economies of the North and South steadily diverged. While the North developed a mixed economy—

Without significant economic diversification, the South developed fewer cities than the North and West. In 1860, it was the least urban region in the country. Whereas nearly 37 percent of New England’s population lived in cities, less than 12 percent of Southerners were urban dwellers. Because the South had so few cities and industrial jobs, it attracted small numbers of European immigrants. Seeking economic opportunity, not competition with slaves (whose labor would keep wages low), immigrants steered northward. In 1860, 13 percent of all Americans were born abroad. But in nine of the fifteen slave states, only 2 percent or less of the population was foreign-

Northerners claimed that slavery was a backward labor system, and compared with Northerners, Southerners invested less of their capital in industry, transportation, and public education. But few Southerners perceived economic weakness in their region. Indeed, planters’ pockets were never fuller than in the 1850s, thanks to the South’s near monopoly on cotton, the hottest commodity in the international marketplace. Planters’ decisions to reinvest in cotton ensured the momentum of the plantation economy and the political and social relationships rooted in it.

REVIEW Why did the nineteenth-