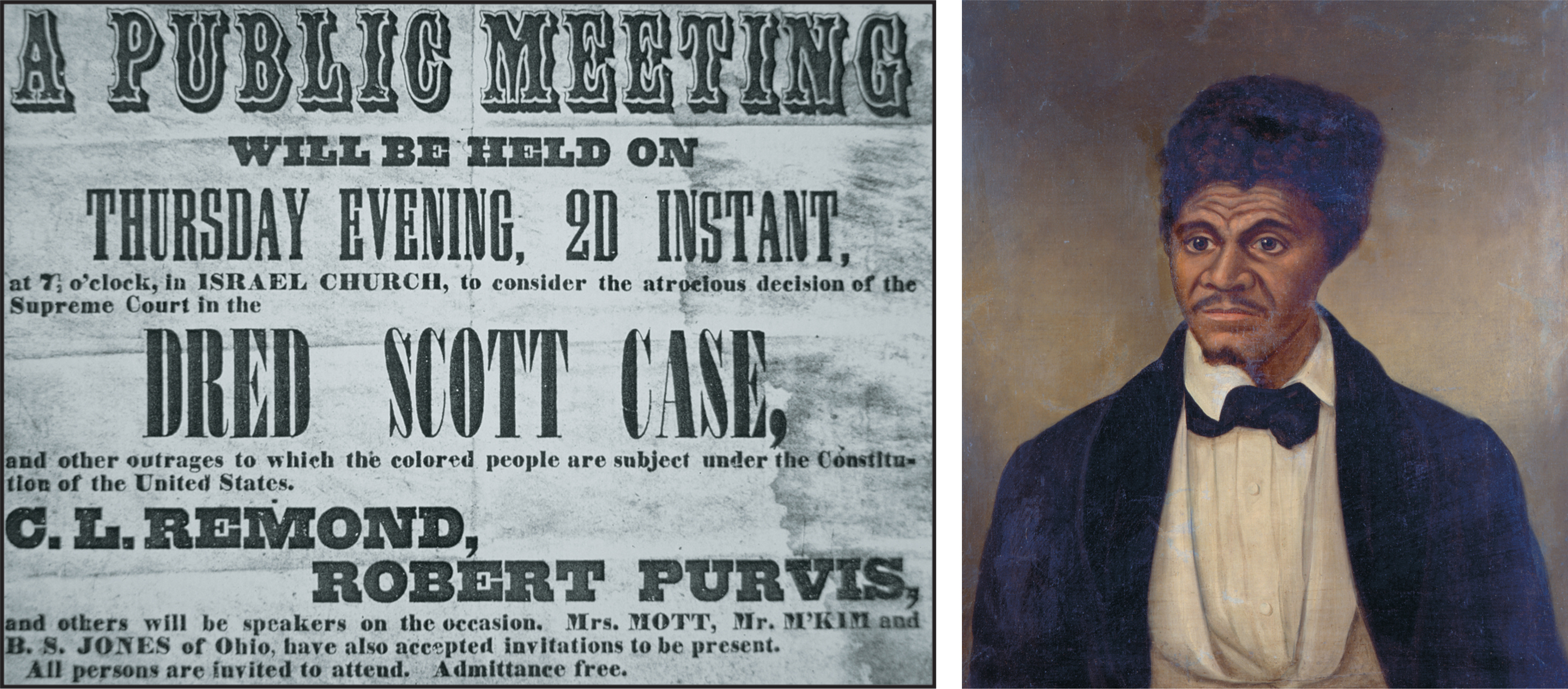

The Dred Scott Decision

Political debate over slavery in the territories became so heated in part because the Constitution lacked precision on the issue. In 1857, in the case of Dred Scott v. Sandford, the Supreme Court announced its understanding of the meaning of the Constitution regarding slavery in the territories. The Court’s decision demonstrated that it enjoyed no special immunity from the sectional and partisan passions that were convulsing the land.

In 1833, an army doctor bought the slave Dred Scott in St. Louis, Missouri, and took him as his personal servant to Fort Armstrong, Illinois, and then to Fort Snelling in Wisconsin Territory. Back in St. Louis in 1846, Scott, with the help of white friends, sued to prove that he and his family were legally entitled to their freedom. Scott argued that living in Illinois, a free state, and Wisconsin, a free territory, had made his family free and that they remained free even after returning to Missouri, a slave state.

In 1857, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, who hated Republicans and detested racial equality, wrote the Court’s Dred Scott decision. First, the Court ruled that Scott could not legally claim violation of his constitutional rights because he was not a citizen of the United States. When the Constitution was written, Taney said, blacks “were regarded as beings of an inferior order . . .

The Taney Court’s extreme proslavery decision outraged Republicans. By denying the federal government the right to exclude slavery in the territories, it cut the legs out from under the Republican Party. Moreover, as the New York Tribune lamented, the decision cleared the way for “all our Territories . . .

The Republican rebuttal to the Dred Scott ruling relied heavily on the dissenting opinion of Justice Benjamin R. Curtis. Scott was a citizen of the United States, Curtis argued. At the time of the writing of the Constitution, free black men could vote in five states and participated in the ratification process. Scott was free. Because slavery was prohibited in Wisconsin, the “involuntary servitude of a slave, coming into the Territory with his master, should cease to exist.” The Missouri Compromise was constitutional. The Founders had meant exactly what they said: Congress had the power to make “all needful rules and regulations” for the territories, including barring slavery.

Unswayed by Curtis’s dissent, the Court in a seven-