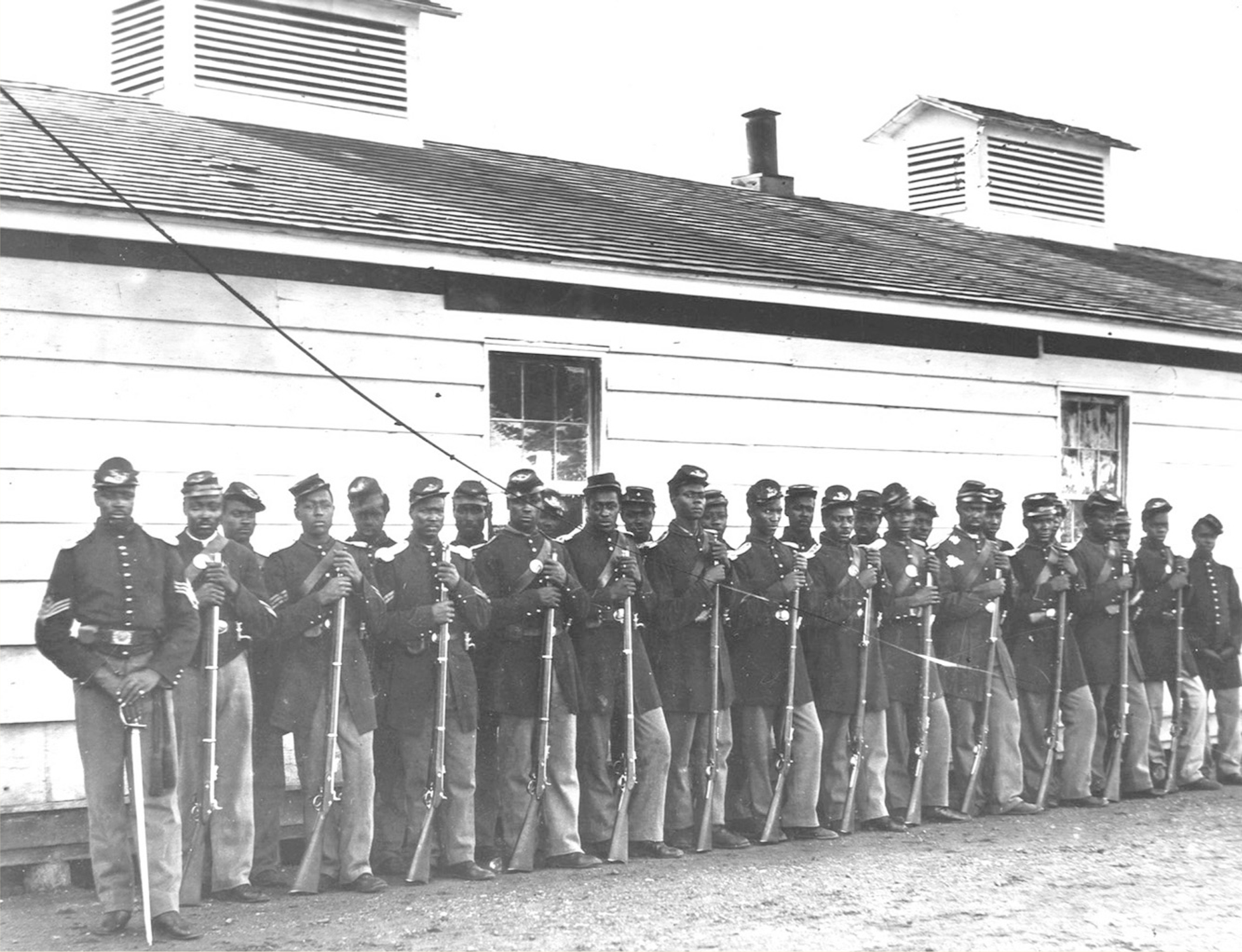

Seeking the American Promise: “The Right to Fight: Black Soldiers in the Civil War”

“Awar undertaken and brazenly carried on for the perpetual enslavement of colored men, calls logically and loudly for colored men to help suppress it,” black leader Frederick Douglass declared at the beginning of the war. But it was only in 1863 that the lengthening casualty lists finally convinced the Lincoln administration to begin aggressively recruiting black soldiers.

In February 1863, James Henry Gooding, a twenty-

Fighting, Gooding said, offered blacks a chance to destroy the “foul aspersion that they were not men.” According to the white commander of the 59th U.S. Colored Infantry, when an ex-

Black courage under fire ended skepticism about the capabilities of African American troops. As one white officer observed after a battle, “They seemed like men who were fighting to vindicate their manhood and they did it well.” The truth is, another remarked, “they have fought their way into the respect of all the army.” After the 54th served courageously in South Carolina, Gooding reported: “It is not for us to blow our horn; but when a regiment of white men gave us three cheers as we were passing them, it shows that we did our duty as men should.”

Yet discrimination within the Union army continued. When the government refused to pay blacks the same as whites, the 54th refused to accept unequal pay. Gooding wrote to President Lincoln himself to explain his regiment’s decision: “Now the main question is, Are we Soldiers, or are we Labourers? . . .

As Union troops advanced deeper into the Confederacy, former slaves greeted black soldiers as heroes. In March 1865, the white officer of a black regiment in North Carolina reported that black soldiers “stepped like lords & conquerors. The frantic demonstrations of the negro population will never die out of my memory. Their cheers & heartfelt ‘God bress ye’s’ & cries of ‘De chains is broke; De chains is broke’ mingled sublimely with the lusty shout of our brave soldiery.” Hardened and disciplined by their military service, black soldiers drew tremendous strength from their participation in the Union effort. Despite their second-

Eager to shoulder the rights, privileges, and responsibilities of freedom, black veterans often took the lead in the hard struggle for equality after the war. Blacks in the Union army that occupied the South after 1865 assumed a special obligation to protect former slaves. “The fact is,” one black chaplain said, “when colored soldiers are about they [whites] are afraid to kick colored women and abuse colored people on the Streets, as they usually do.” Black veterans believed that their military service entitled African Americans not only to freedom but also to civil and political rights. Sergeant Henry Maxwell announced: “We want two more boxes besides the cartridge box—

James Henry Gooding did not have a chance to participate in the postwar struggle for equal rights. Wounded and captured at the battle of Olustee in Florida, he was sent to the infamous Confederate prison Andersonville, where he died on July 19, 1864.

Questions for Consideration

- Why did the Union resist enrolling black troops?

- Why was the right to fight so important to black men?

- How did military service affect black men?

Connect to the Big Idea

In what ways do you think military service by black men would have been important to the entire black community?