Historical Question: “Why Did So Many Soldiers Die?”

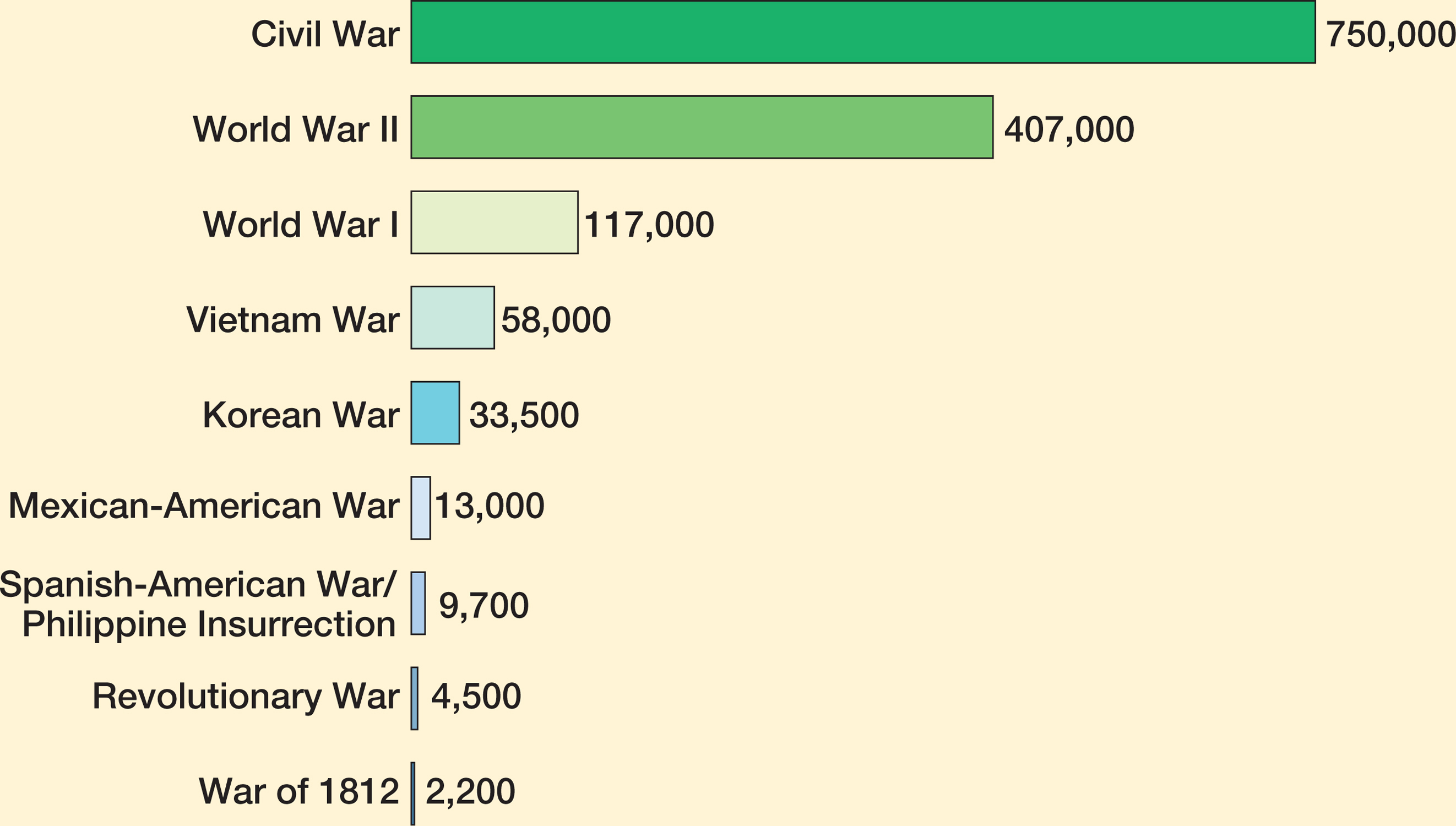

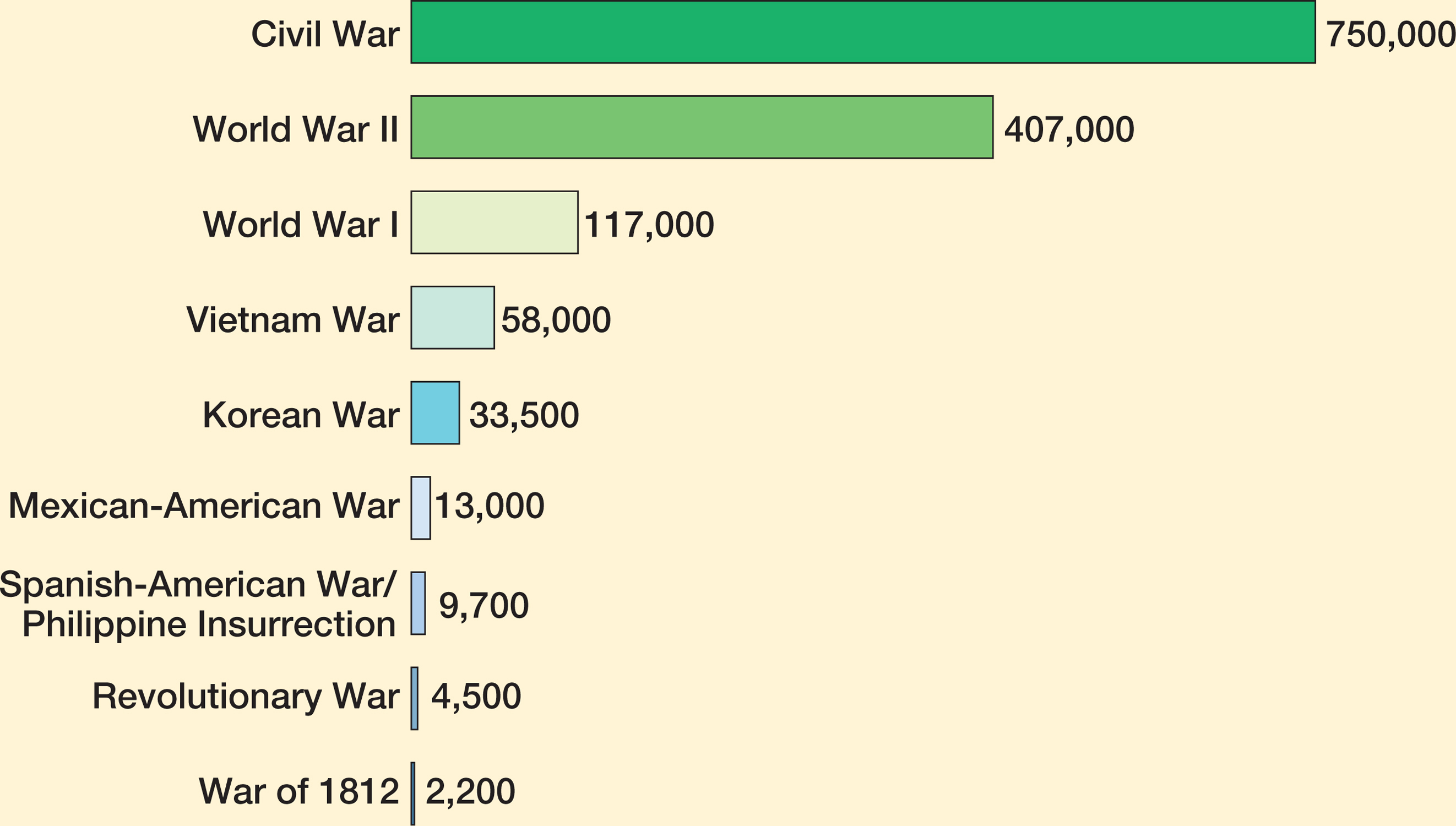

FIGURE 15.3 Civil War Deaths The loss of life in the Civil War—as many as 750,000—was greater than the losses in all other American wars through the Vietnam War combined.

The American Civil War was the bloodiest conflict in American history (Figure 15.3). Precise numbers are hard to determine, but as many as 750,000 soldiers died. Why were the Civil War totals so horrendous?

This question is almost as old as the war itself, and in answering it historians have traditionally pointed to a variety of explanations: the scale and duration of the fighting; military strategy; battlefield technology; and the backward state of medicine. The sheer size of the armies—some battles involved more than 200,000 soldiers—ensured that battlefields would turn red with blood. Moreover, what most Americans expected to be a short war extended for four full years. In addition, armies fought with antiquated Napoleonic strategy. In the generals’ eyes, the ideal soldier advanced with his comrades in a compact, close-order formation. But by the 1860s, military technology had made such frontal assaults deadly. Weapons with rifled barrels were replacing smoothbore muskets and cannons, and the new weapons’ greater range and accuracy made sitting ducks of charging infantry units. As a result, battles took thousands of lives in a single day. On July 2, 1862, the morning after the battle at Malvern Hill in Virginia, a Union officer surveyed the scene: “Over 5,000 dead and wounded men were on the ground . . . enough were alive and moving to give to the field a singular crawling effect.”

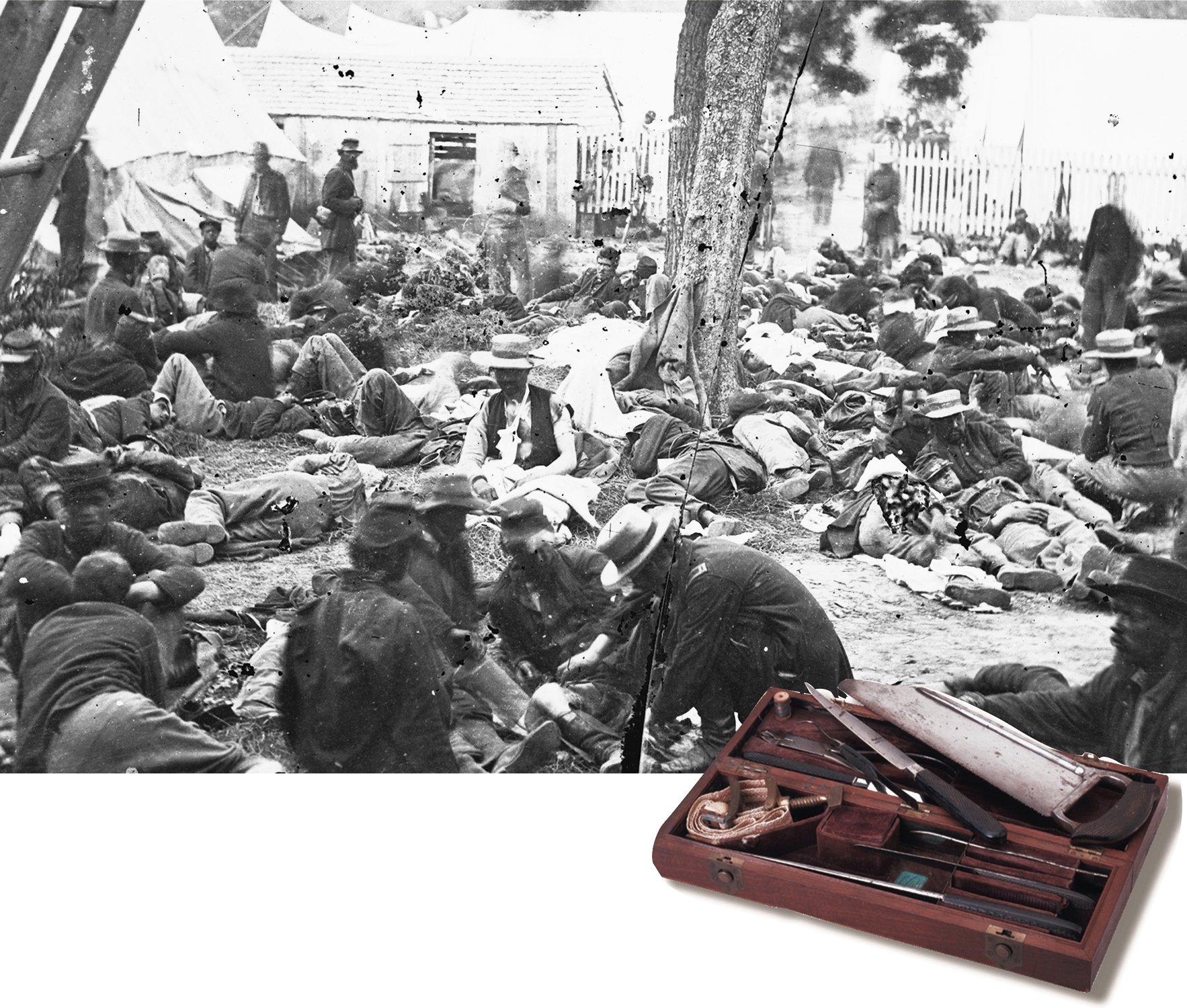

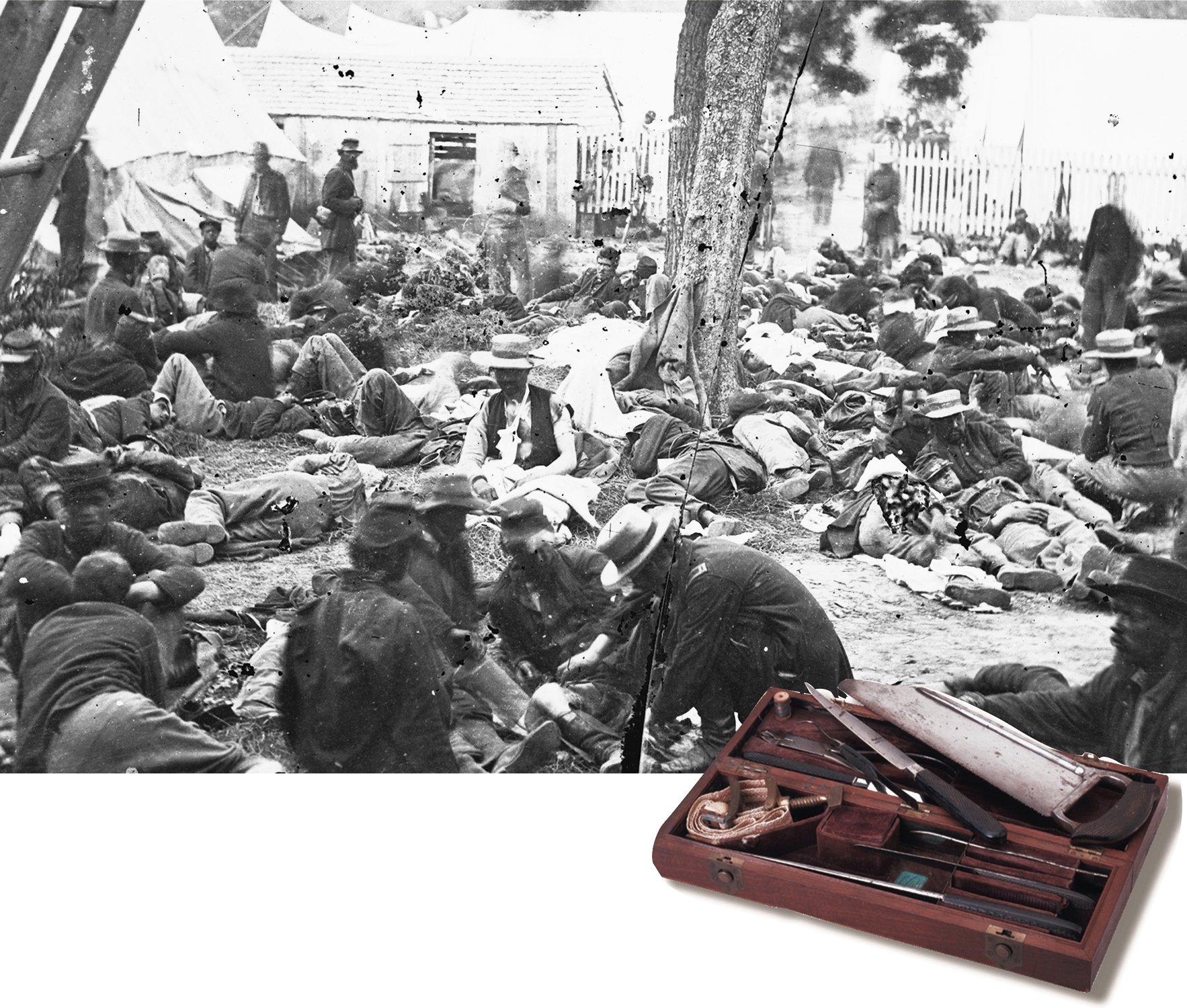

Wounded Men at Savage’s Station Misery did not end when the cannons ceased firing. Northern and southern surgeons performed approximately 60,000 amputations with simple instruments such as those included in this surgical kit. The wounded men shown here were but a faction of those injured or killed during General George McClellan’s peninsula campaign in 1862. Photo: Library of Congress; Surgical kit: © Chicago History Museum, USA / The Bridgeman Art Library.

When the war began, Union and Confederate medical departments could not cope with skirmishes, much less large-scale battles. They had no ambulance corps to remove the wounded from the scene. They had no field hospitals. Wounded soldiers often lay on battlefields for hours, sometimes days. Only the shock of massive casualties compelled reform. Gradually, both North and South organized effective ambulance corps, built hospitals, and hired trained surgeons and nurses.

Soldiers did not always count speedy transportation to a hospital as a blessing, however. As one Union soldier said, “I had rather risk a battle than the Hospitals.” Field doctors gained a reputation as butchers, but a wounded man’s real enemy was medical ignorance. Physicians had almost no knowledge of the cause and transmission of disease or the benefits of antiseptics. Unaware of basic germ theory, surgeons spread infection almost every time they operated. They wore the same bloody smocks for days and washed their hands and their scalpels and saws in buckets of dirty water. Although surgeons used anesthesia (both ether and chloroform), soldiers often did not survive amputations, not because of the operations but because of the gangrene that inevitably followed. A Union doctor discovered in 1864 that bromine arrested gangrene, but the best that most amputees could hope for was maggots, which ate dead flesh on the stump and thus inhibited the spread of infection. The growing ranks of nurses, including Dorothea Dix and Clara Barton, improved wounded men’s odds and alleviated their suffering. Still, during the Civil War, nearly one of every five wounded rebel soldiers died, and one of every six Yankees. A century later, in Vietnam, only one wounded American soldier in four hundred died.

Soldiers who avoided battlefield wounds and hospital infections still faced sickness. Deadly diseases such as dysentery and typhoid swept through crowded army camps, where latrines were often dangerously close to drinking-water supplies, and mosquitoes, flies, and body lice were more than nuisances. Pneumonia and malaria also cut down thousands. Quinine from South America proved an effective treatment for malaria, but by the end of the war the going price was $500 an ounce. Civilian relief agencies promoted hygiene in army camps and made some headway. Nevertheless, disease killed nearly twice as many soldiers as did combat. Many who died of disease were prisoners of war. Approximately 30,000 Northerners died in Confederate prisons, and approximately 26,000 Southerners died in Union prisons.

Recently, historians have probed another explanation for the death toll, turning to soldiers’ cultural attitudes and values to explain why they were willing to die in such great numbers. Some have explored how the nineteenth-century code of masculinity propelled valor on the battlefields, and how patriotism, for either the Union or the Confederacy, moved soldiers to risk everything. But scholars have focused most especially on how soldiers’ religious beliefs about death made it easier for them to negotiate dying. The triumph of evangelical Protestantism in the early nineteenth century meant that Civil War soldiers faced death with calm resignation. They believed in a heaven that promised bodily resurrection and family reunion; the assurance of everlasting life, therefore, made it easier to face death. Culture, then, as well as the scope and length of the war, strategy, technology, and primitive medicine, helps explain the war’s tremendous carnage.

Questions for Consideration

- In what ways were Civil War strategists fighting the world’s first “modern” war? In what ways were they still fighting a traditional-style war? How does this contrast account for the number of dead and wounded soldiers?

- How did the high casualty rates lead to new opportunities for both women and blacks?

Which economy—the Union’s or the Confederacy’s—was better able to cope with the loss of manpower to the military, and why?