Historical Question: “Social Darwinism: Did Wealthy Industrialists Practice What They Preached?”

Darwinism, with its emphasis on tooth-

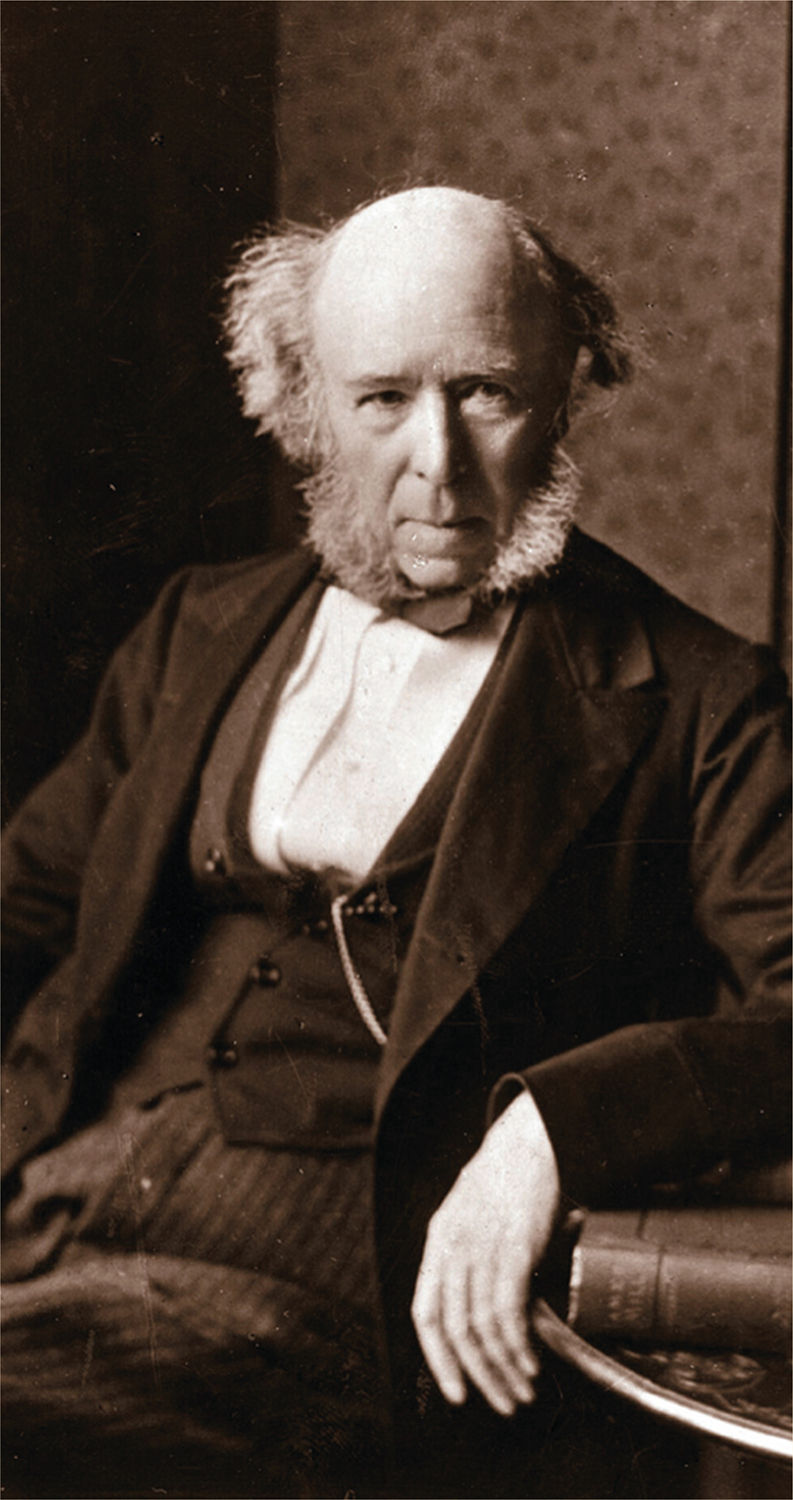

Andrew Carnegie, alone among the American business moguls, not only championed social Darwinism but also avidly read the works of its primary exponent, the British social philosopher Herbert Spencer. Significantly, Spencer, not Darwin, coined the catchphrase “survival of the fittest.” Carnegie spoke of his indebtedness to Spencer in terms usually reserved for religious conversion: “Before Spencer, all for me had been darkness, after him, all had become light—

Not content to worship Spencer from afar, Carnegie assiduously worked to make his acquaintance and then would not rest until he had convinced the reluctant Spencer to come to America. In Pittsburgh, Carnegie promised, Spencer could best view his evolutionary theories at work in the world of industry. Clearly, Carnegie viewed his steelworks as the apex of America’s new industrial order, a testimony to the playing out of evolutionary theory in the economic world.

In 1882, Spencer undertook an American tour. Carnegie personally invited him to Pittsburgh, squiring him through the Braddock steel mills. But Spencer failed to appreciate Carnegie’s achievement. The heat, noise, and pollution of Pittsburgh reduced Spencer to near collapse, and he could only choke out, “Six months’ residence here would justify suicide.” Carnegie must have been devastated.

How well Carnegie actually understood the principles of social Darwinism is debatable. In his 1900 essay “Popular Illusions about Trusts,” Carnegie spoke of the “law of evolution that moves from the heterogeneous to the homogeneous,” citing Spencer as his source. Spencer, however, had written of the movement “from an indefinite incoherent homogeneity to a definite coherent heterogeneity.” Instead of acknowledging that the history of human evolution moved from the simple to the more complex, Carnegie seemed to insist that evolution moved from the complex to the simple. This confusion of the most basic evolutionary theory calls into question Carnegie’s grasp of Spencer’s ideas or indeed of Darwin’s. Other business leaders too busy making money to read no doubt understood even less about the working of evolutionary theory and social Darwinism, which they so often claimed as their own.

The distance between preachment and practice is boldly evident in the example of William Graham Sumner, America’s foremost social Darwinist. Ironically, Sumner, who often sounded like an apologist for the rich, aroused the wrath of the very group he championed. The problem was that strict social Darwinists like Sumner insisted absolutely that the government ought not to meddle in the economy. The purity of Sumner’s commitment to laissez-

Inconsistency never seemed to trouble Carnegie, who did not acknowledge a contradiction between his worship of Spencer and his strong support for the tariff. The comparison of Carnegie’s position and Sumner’s underscores the reality that although in theory laissez-

Questions for Consideration

- In what ways did American business moguls think that the notion of evolution applied to them?

- Why were most industrialists inconsistent in invoking the principles of social Darwinism?

Connect to the Big Idea

How had American industrialism transformed life for ordinary Americans?