The Family Economy: Women and Children

In 1900, the typical male worker in manufacturing earned $500 a year, about $12,000 in today’s dollars. Many working-class families, whether native-born or immigrant, lived in or near poverty, their economic survival dependent on the contributions of all family members, regardless of sex or age. “Father,” asked one young immigrant girl, “does everybody in America live like this? Go to work early, come home late, eat and go to Sleep? And the next day again work, eat, and sleep?” Most workers did. The family economy meant that everyone contributed to maintain even the most meager household.

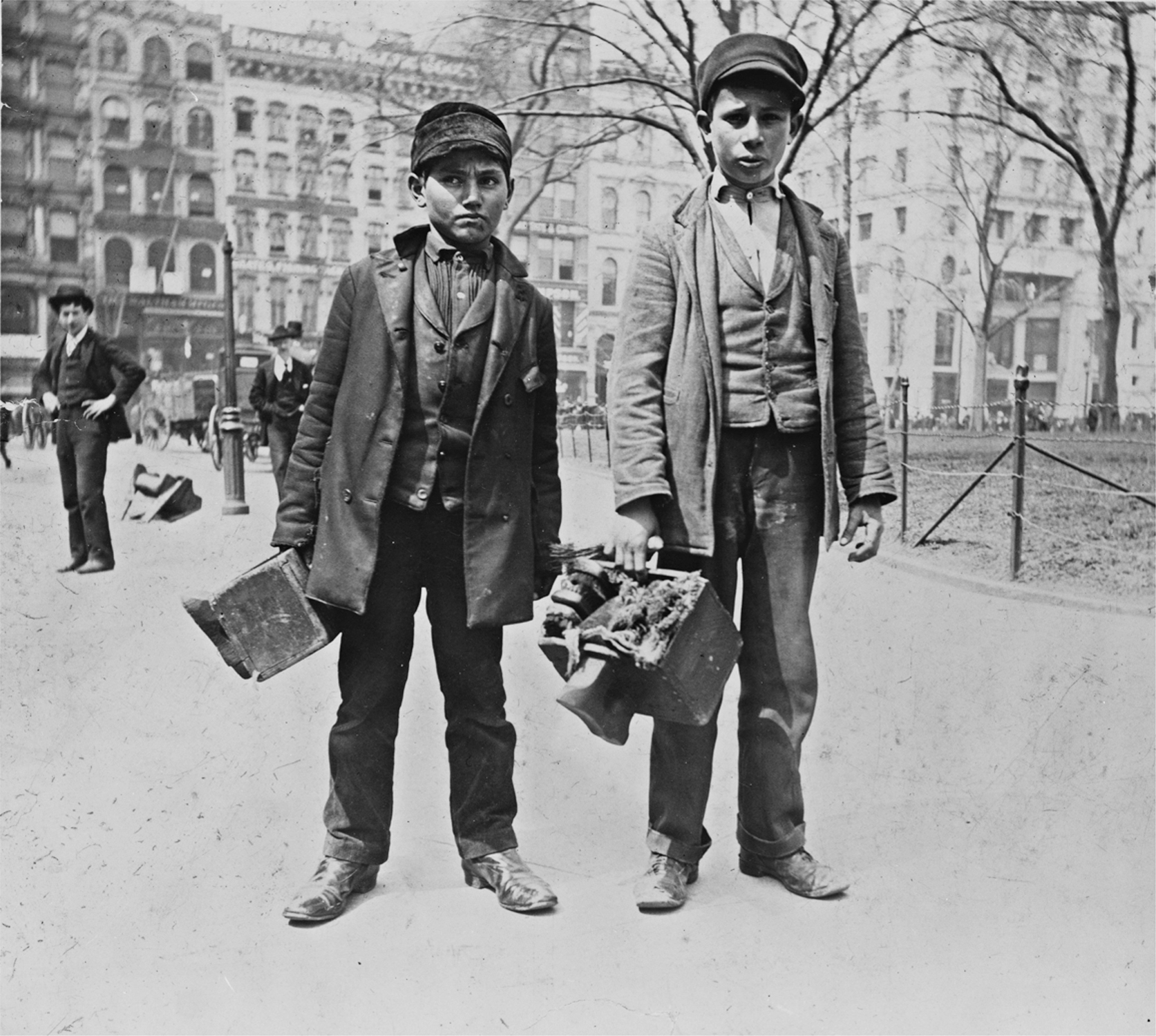

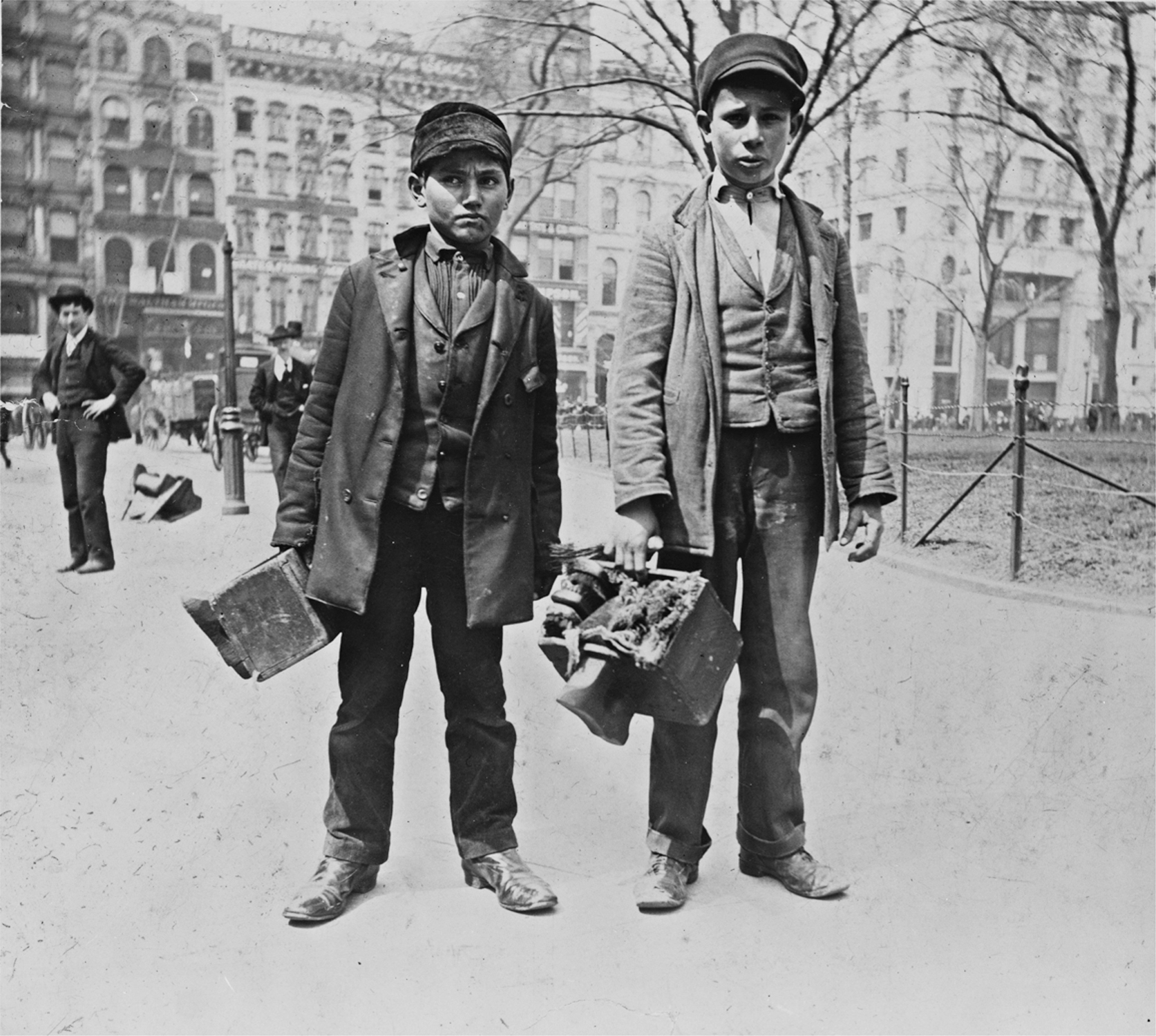

In the cities, boys as young as six years old plied their trades as bootblacks and newsboys. Often working under an adult contractor, these children earned as little as fifty cents a day. Many of them were homeless—orphaned or cast off by their families. “We wuz six, and we ain’t got no father,” a child of twelve told reporter Jacob Riis. “Some of us had to go.”

Bootblacks The faces and hands of the two bootblacks shown here on a New York City street in 1896 testify to their grimy trade. Boys as young as six worked as bootblacks and newsboys, often for contractors who took a cut of their meager earnings. When families could no longer afford to feed their children, young boys often headed out on their own. Library of Congress.

Child labor increased each decade after 1870. The percentage of children under fifteen engaged in paid labor did not drop until after World War I. The 1900 census estimated that 1,750,178 children ages ten to fifteen were employed, an increase of more than a million over thirty years. Children in this age range constituted more than 18 percent of the industrial labor force.

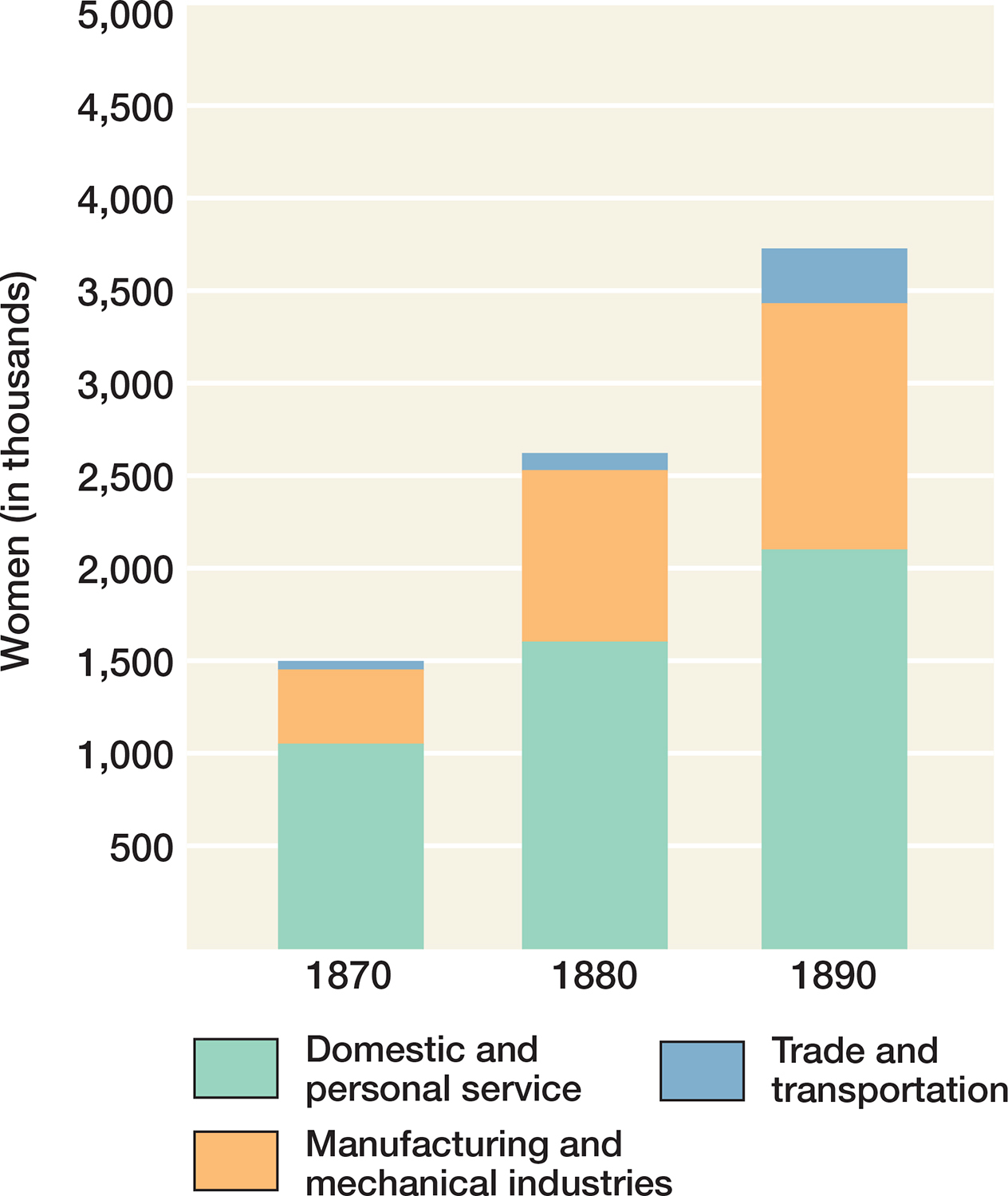

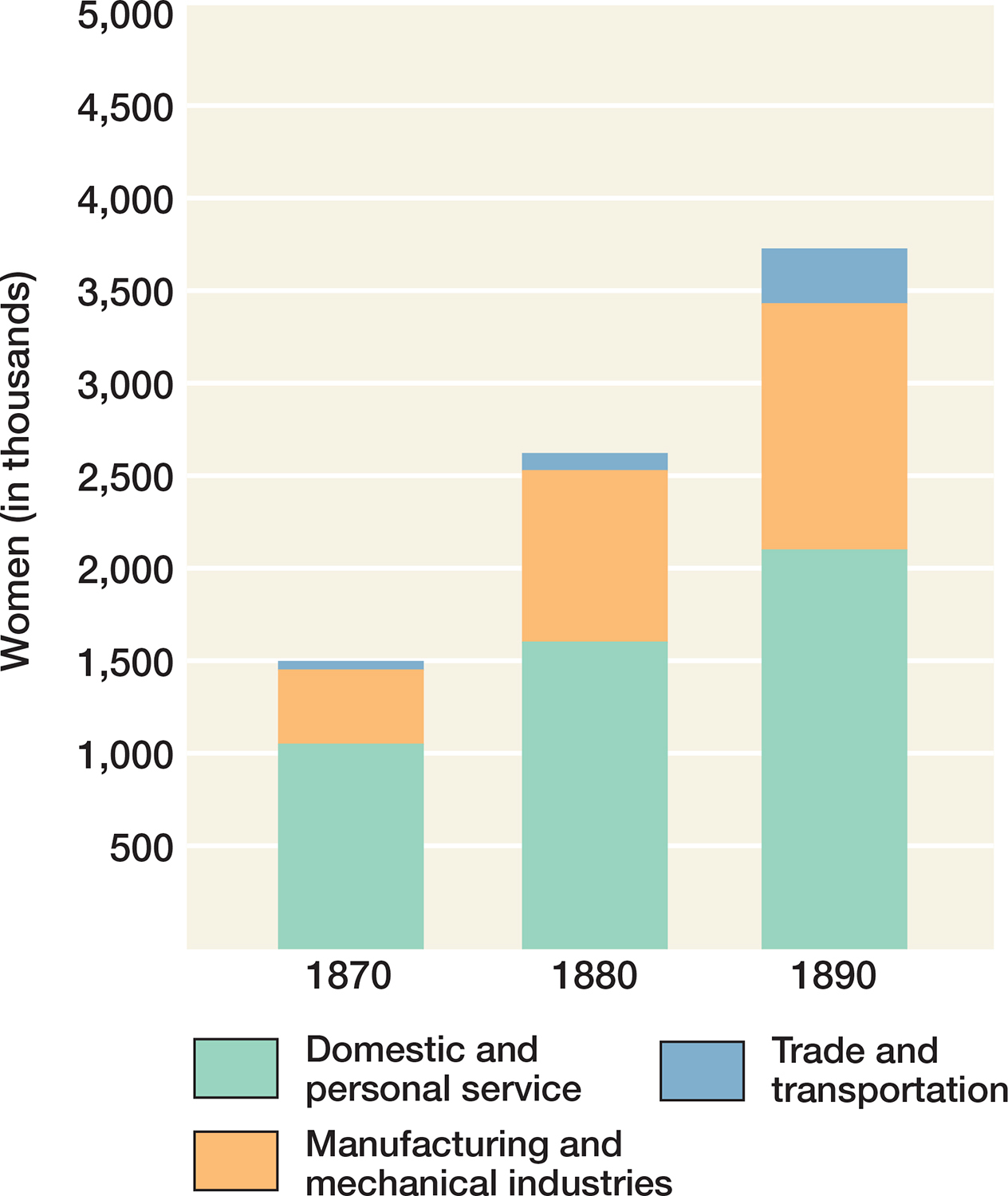

Women working for wages in nonagricultural occupations more than doubled in number between 1870 and 1900 (Figure 19.3). Yet white married women, even among the working class, rarely worked for wages outside the home. In 1890, only 3 percent were employed. Black women, married and unmarried, worked out of the home for wages in much greater numbers. The 1890 census showed that 25 percent of married African American women were employed, often as domestics in the houses of white families.

FIGURE 19.3 Women and Work, 1870–1890 In 1870, close to 1.5 million women worked in nonagricultural occupations. By 1890, that number had more than doubled to 3.7 million. More and more women sought work in manufacturing and mechanical industries, although domestic service still constituted the largest employment arena for women.