Frances Willard and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union

A visionary leader, Frances Willard spoke for a group left almost entirely out of the U.S. electoral process. In 1890, only one state, Wyoming, allowed women to vote in national elections. But lack of the franchise did not mean that women were apolitical. The WCTU demonstrated the breadth of women’s political activity in the late nineteenth century.

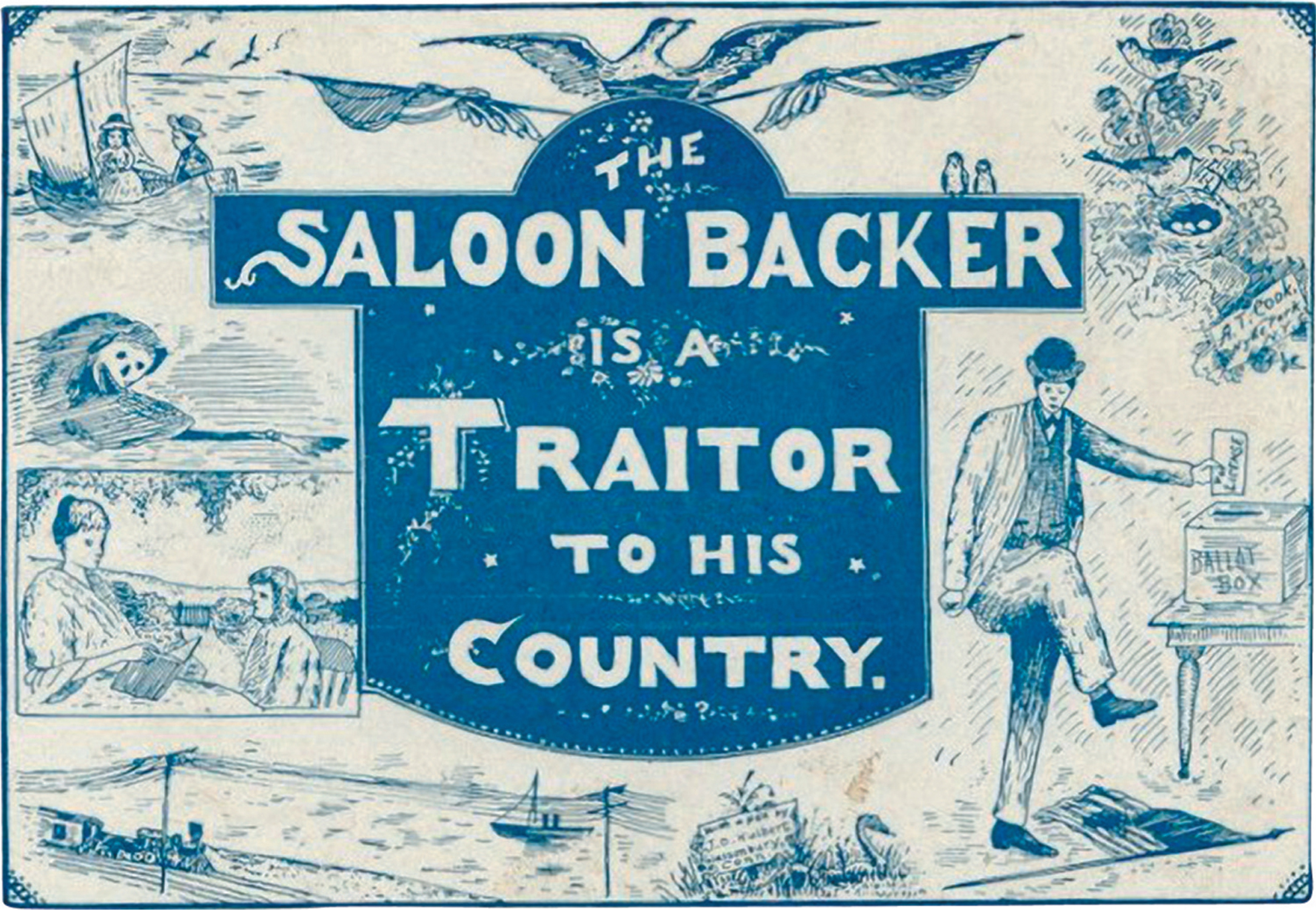

Women supported the temperance movement because they felt particularly vulnerable to the effects of drunkenness. Dependent on men’s wages, married women and their children suffered when money went for drink. The drunken, abusive husband epitomized the evils of a nation in which women remained second-

When Willard became president in 1879, she radically changed the direction of the organization. Social action replaced prayer as women’s answer to the threat of drunkenness. Viewing alcoholism as a disease rather than a sin and poverty as a cause rather than a result of drink, the WCTU became involved in labor issues, joining with the Knights of Labor to press for better working conditions for women workers. Describing workers in a textile mill, a WCTU member wrote in the organization’s Union Signal magazine, “It is dreadful to see these girls, stripped almost to the skin . . .

Willard capitalized on the cult of domesticity as a shrewd political tactic. Using “home protection” as her watchword, she argued as early as 1884 that women needed the vote to protect home and family. By the 1890s, the WCTU’s grassroots network of local unions included 200,000 dues paying members and had spread to all but the most isolated rural areas of the country.

Willard worked to create a broad reform coalition in the 1890s, embracing the Knights of Labor, the People’s Party, and the Prohibition Party. Until her death in 1898, she led if not a woman’s rights movement, then the first organized mass movement of women united around a woman’s issue. By 1900, thanks largely to the WCTU, women could claim a generation of experience in political action—