Markets and Missionaries

The depression of the 1890s provided a powerful impetus to American commercial expansion. As markets weakened at home, American businesses looked abroad for profits. As the depression deepened, one diplomat warned that Americans “must turn [their] eyes abroad, or they will soon look inward upon discontent.”

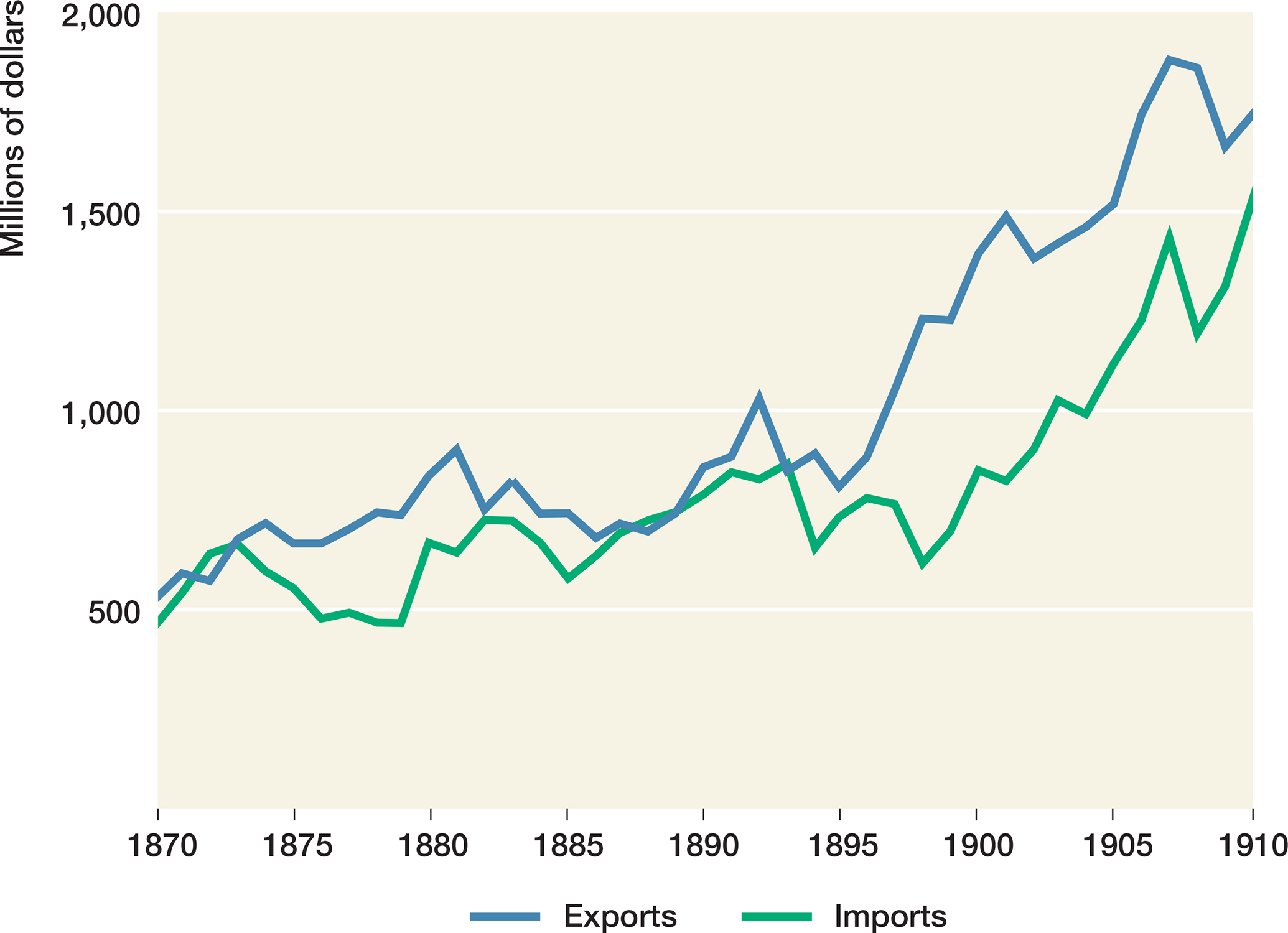

Exports constituted a small but significant percentage of the profits of American business in the 1890s (Figure 20.2). And where American interests led, businessmen expected the government’s power and influence to follow to protect their investments. Companies like Standard Oil actively sought to use the U.S. government as their agent, often putting foreign service employees on the payroll. “Our ambassadors and ministers and consuls,” wrote John D. Rockefeller appreciatively, “have aided to push our way into new markets and to the utmost corners of the world.”

America’s foreign policy often appeared little more than a sidelight to business development. In Hawai’i (first called the Sandwich Islands), American sugar interests fomented a rebellion in 1893, toppling the increasingly independent Queen Lili’uokalani. (See “Beyond America’s Borders.”) They pushed Congress to annex the islands to avoid the high McKinley tariff on sugar. When President Cleveland learned that Hawai’ians opposed annexation, he withdrew the proposal from Congress. But expansionists still coveted the islands and looked for an opportunity to push through annexation.

Business interests alone did not account for the new expansionism that seized the nation during the 1890s. As Alfred Thayer Mahan, leader of a growing group of American expansionists, confessed, “Even when material interests are the original exciting cause, it is the sentiment to which they give rise, the moral tone which emotion takes that constitutes the greater force.” Much of that moral tone was set by American missionaries intent on spreading the gospel of Christianity to the “heathen.” No area on the globe constituted a greater challenge than China.

An 1858 agreement, the Tianjin (Tientsin) treaty, admitted foreign missionaries to China. Although Christians converted only 100,000 in a population of 400 million, the Chinese nevertheless resented the interference of missionaries in village life. Opposition to foreign missionaries took the form of antiforeign secret societies, most notably the Boxers, whose Chinese name translated to “Righteous Harmonious Fist.” In 1899, the Boxers hunted down and killed Chinese Christians and missionaries in northwestern Shandong Province. With the tacit support of China’s Dowager Empress, the Boxers, shouting “Uphold the Ch’ing Dynasty, Exterminate the Foreigners,” marched on the cities. Their rampage eventually led to the massacre of some 30,000 Chinese converts and 250 foreign nuns, priests, and missionaries.

As the Boxer’s spread terror throughout northern China, some 800 Americans and Europeans sought refuge in the foreign diplomatic buildings in Peking (today’s Beijing). Along with missionaries from the countryside came thousands of their Chinese converts. Unable to escape and cut off from outside aid and communication, the Americans and Europeans in Beijing mounted a defense to face the Boxer onslaught. One American described the scene as 20,000 Boxers stormed the walls in June 1900:

Their yells were deafening, while the roar of gongs, drums, and horns sounded like thunder. . . .

For two months the little group held out under siege, eating mule and horse meat and losing 76 men in battle. Sarah Conger, wife of the U.S. ambassador, wrote wearily, “[The siege] was exciting at first, but night after night of this firing, horn-

In August 1900, 2,500 U.S. troops joined an international force sent to rescue the foreigners and put down the uprising in the Chinese capital. The European powers imposed the humiliating Boxer Protocol in 1901, giving themselves the right to maintain military forces in Beijing and requiring the Chinese government to pay an exorbitant indemnity of $333 million.

In the aftermath of the Boxer uprising, missionaries voiced no concern at the paradox of bringing Christianity to China at gunpoint. “It is worth any cost in money, worth any cost in bloodshed,” argued one bishop, “if we can make millions of Chinese true and intelligent Christians.” Merchants and missionaries alike shared such moralistic reasoning. Indeed, they worked hand in hand; trade and Christianity marched into Asia together. “Missionaries,” admitted the American clergyman Charles Denby, “are the pioneers of trade and commerce. . . .