“A Splendid Little War”

The Spanish-

Looking back on the Spanish-

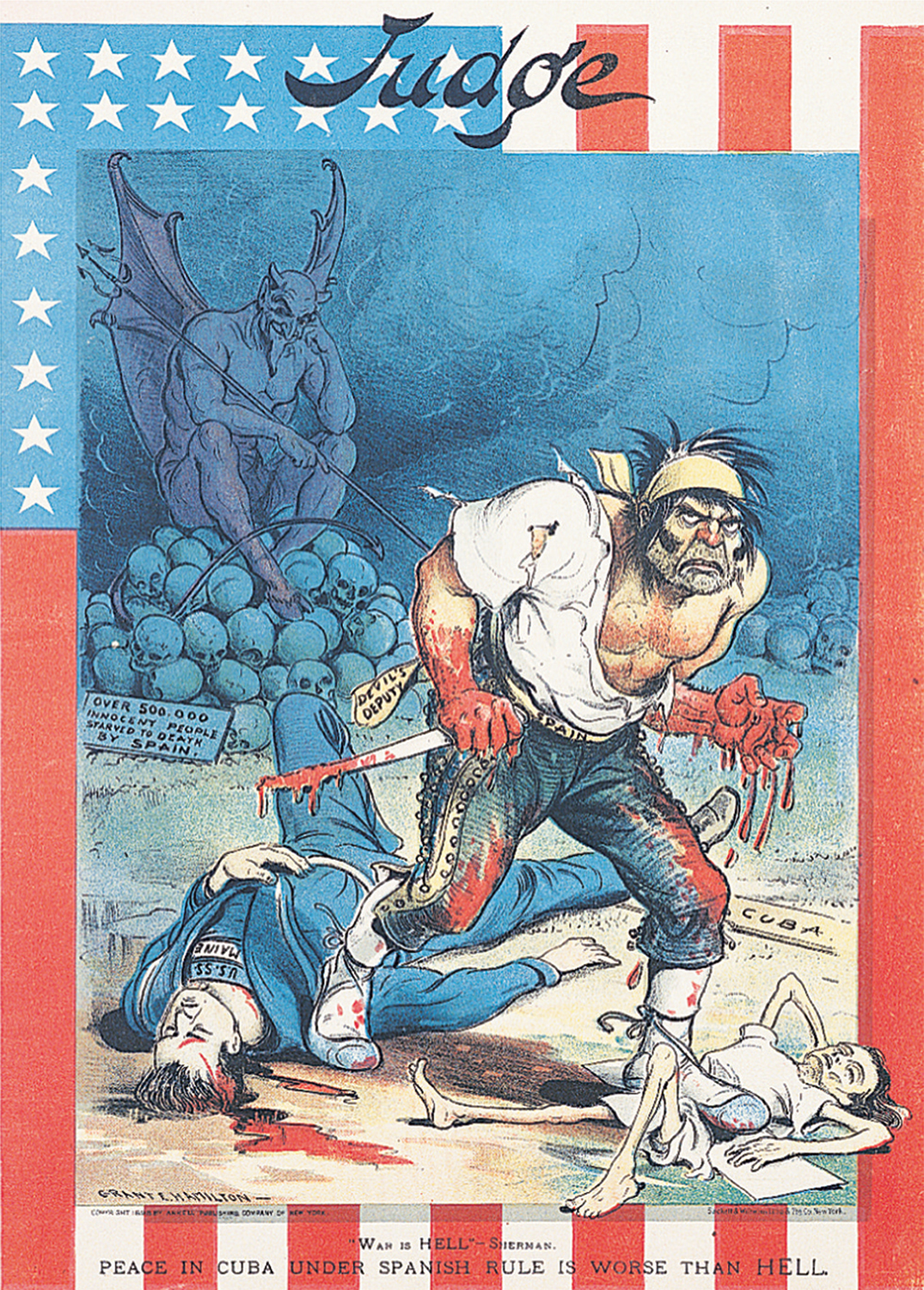

The war began with moral outrage over the treatment of Cuban revolutionaries, who had launched a fight for independence against the Spanish colonial regime in 1895. In an attempt to isolate the guerrillas, the Spanish general Valeriano Weyler herded Cubans into crowded and unsanitary concentration camps, where thousands died of hunger, disease, and exposure. Starvation soon spread to the cities. By 1898, fully a quarter of the island’s population had perished in the Cuban revolution.

As the Cuban rebellion dragged on, pressure for American intervention mounted. American newspapers fueled public outrage at Spain. A fierce circulation war raged in New York City between William Randolph Hearst’s Journal and Joseph Pulitzer’s World. Their competition provoked what came to be called yellow journalism, named for the colored ink used in a popular comic strip. The Cuban war provided a wealth of dramatic copy. Newspapers fed the American people a daily diet of “Butcher” Weyler and Spanish atrocities. Hearst sent artist Frederic Remington to document the horror, and when Remington wired home, “There is no trouble here. There will be no war,” Hearst shot back, “You furnish the pictures and I’ll furnish the war.”

American interests in Cuba were, in the words of the U.S. minister to Spain, more than “merely theoretical or sentimental.” American business had more than $50 million invested in Cuban sugar, and American trade with Cuba, a brisk $100 million a year before the rebellion, had dropped to near zero. Nevertheless, the business community balked, wary of a war with Spain. When industrialist Mark Hanna, the Republican kingmaker and senator from Ohio, urged restraint, a hotheaded Theodore Roosevelt exploded, “We will have this war for the freedom of Cuba, Senator Hanna, in spite of the timidity of commercial interests.”

To expansionists like Roosevelt, more than Cuban independence was at stake. As assistant secretary of the navy, Roosevelt took the helm in the absence of his boss and, in the summer of 1897, audaciously ordered the U.S. fleet to be ready to steam to Manila in the Philippines. In the event of conflict with Spain, Roosevelt put the navy in a position to capture the islands and gain a stepping-

President McKinley moved slowly toward intervention. In a show of American force, he dispatched the battleship Maine to Cuba. On the night of February 15, 1898, a mysterious explosion destroyed the Maine, killing 267 crew members. The source of the explosion remained unclear, but inflammatory stories in the press enraged Americans. (See “Historical Question”). Rallying to the cry “Remember the Maine,” Congress declared war on Spain. In a surge of patriotism, more than a million men rushed to enlist. War brought with it a unity of purpose and national harmony that ended a decade of political dissent and strife. “In April, everywhere over this good fair land, flags were flying,” wrote Kansas editor William Allen White. “At the stations, crowds gathered to hurrah for the soldiers, and to throw hats into the air, and to unfurl flags.”

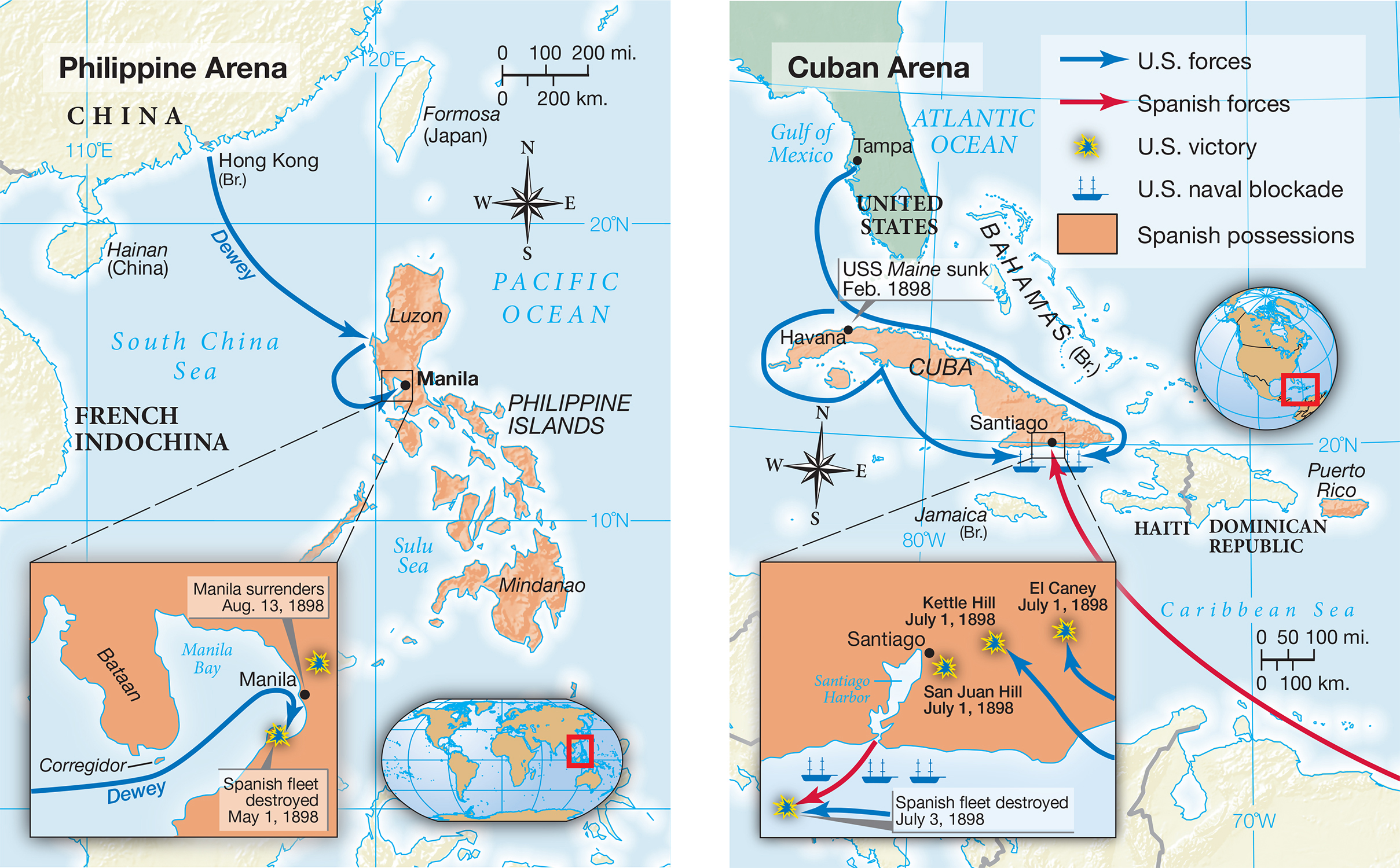

Five days after McKinley signed the war resolution, a U.S. Navy squadron destroyed the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay (Map 20.3). The stunning victory caught most Americans by surprise. Few had ever heard of the Philippines. Even McKinley confessed that he could not locate the archipelago on the map. Nevertheless he dispatched U.S. troops to secure the islands.

The war in Cuba ended almost as quickly as it began. The first troops landed on June 22, and after a handful of battles the Spanish forces surrendered on July 17. The war lasted just long enough to elevate Theodore Roosevelt to the status of bona fide war hero. Roosevelt resigned his navy post and formed the Rough Riders, a regiment composed of a sprinkling of Ivy League polo players and a number of western cowboys Roosevelt befriended during his stint as a cattle rancher in the Dakotas. The Rough Riders’ charge up Kettle Hill and Roosevelt’s role in the decisive battle of San Juan Hill made front-