Progressives and the Working Class

Day-

Attempts to forge a cross-

The WTUL’s most notable success came in 1909 in the “uprising of the twenty thousand,” when hundreds of women employees of the Triangle Shirtwaist Company in New York City went on strike to protest low wages, dangerous working conditions, and management’s refusal to recognize their union, the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union. In support, an estimated twenty thousand garment workers, most of them teenage girls and many of them Jewish and Italian immigrants, stayed out on strike through the winter, picketing in the bitter cold. Police and hired thugs harassed the picketing strikers, beating them up and arresting more than six hundred of them for “street walking” (prostitution). When WTUL allies, including J. P. Morgan’s daughter Anne, joined the picket line, the harassment quickly stopped. By the time the strike ended in February 1910, the workers had won important demands in many shops. The solidarity shown by the women workers proved to be the strike’s greatest achievement. As Clara Lemlich, one of the strike’s leaders, exclaimed, “They used to say that you couldn’t even organize women. They wouldn’t come to union meetings. They were ‘temporary’ workers. Well we showed them!”

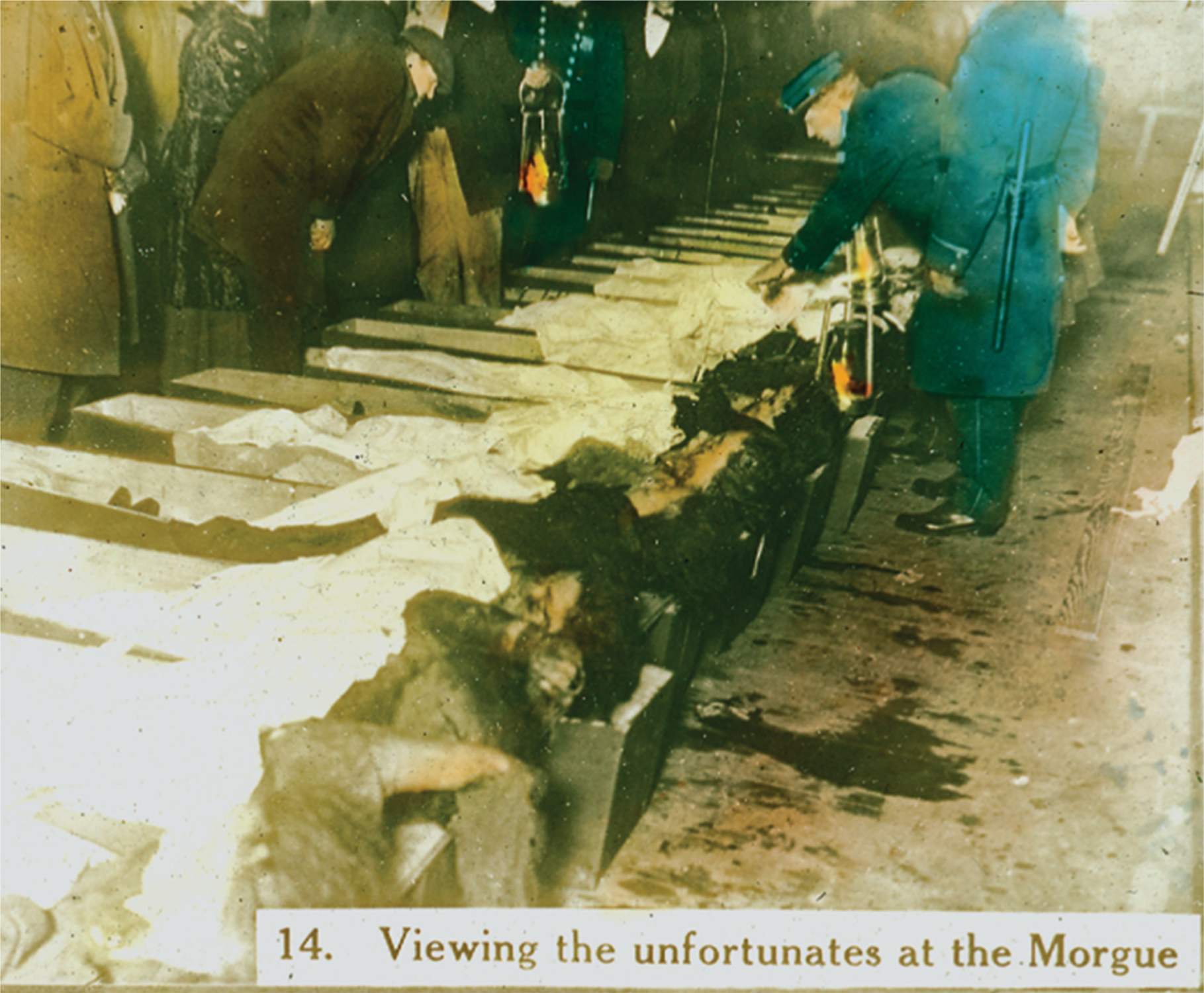

But for all its success, the uprising of the twenty thousand failed fundamentally to change conditions for women workers, as the tragic Triangle fire dramatized in 1911. A little over a year after the shirtwaist makers’ strike ended, fire alarms sounded at the Triangle Shirtwaist factory. The ramshackle building, full of lint and combustible cloth, burned to rubble in half an hour. A WTUL member described the scene below on the street: “Two young girls whom I knew to be working in the vicinity came rushing toward me, tears were running from their eyes and they were white and shaking as they caught me by the arm. ‘Oh,’ shrieked one of them, ‘they are jumping. Jumping from ten stories up! They are going through the air like bundles of clothes.’ ”

The terrified Triangle workers had little choice but to jump. Flames blocked one exit, and the other door had been locked to prevent workers from pilfering. The flimsy, rusted fire escape collapsed under the weight of fleeing workers, killing dozens. Trapped, 54 workers on the top floors jumped to their deaths. Of 500 workers, 146 died and scores of others were injured. The owners of the Triangle firm went to trial for negligence, but they avoided conviction when authorities determined that a careless smoker had started the fire. The Triangle Shirt-

Outrage and a sense of futility overwhelmed Rose Schneiderman, a leading WTUL organizer, who made a bitter speech at the memorial service for the dead Triangle workers. “I would be a traitor to those poor burned bodies if I came here to talk good fellowship,” she told her audience. “We have tried you good people of the public and we have found you wanting. . . .

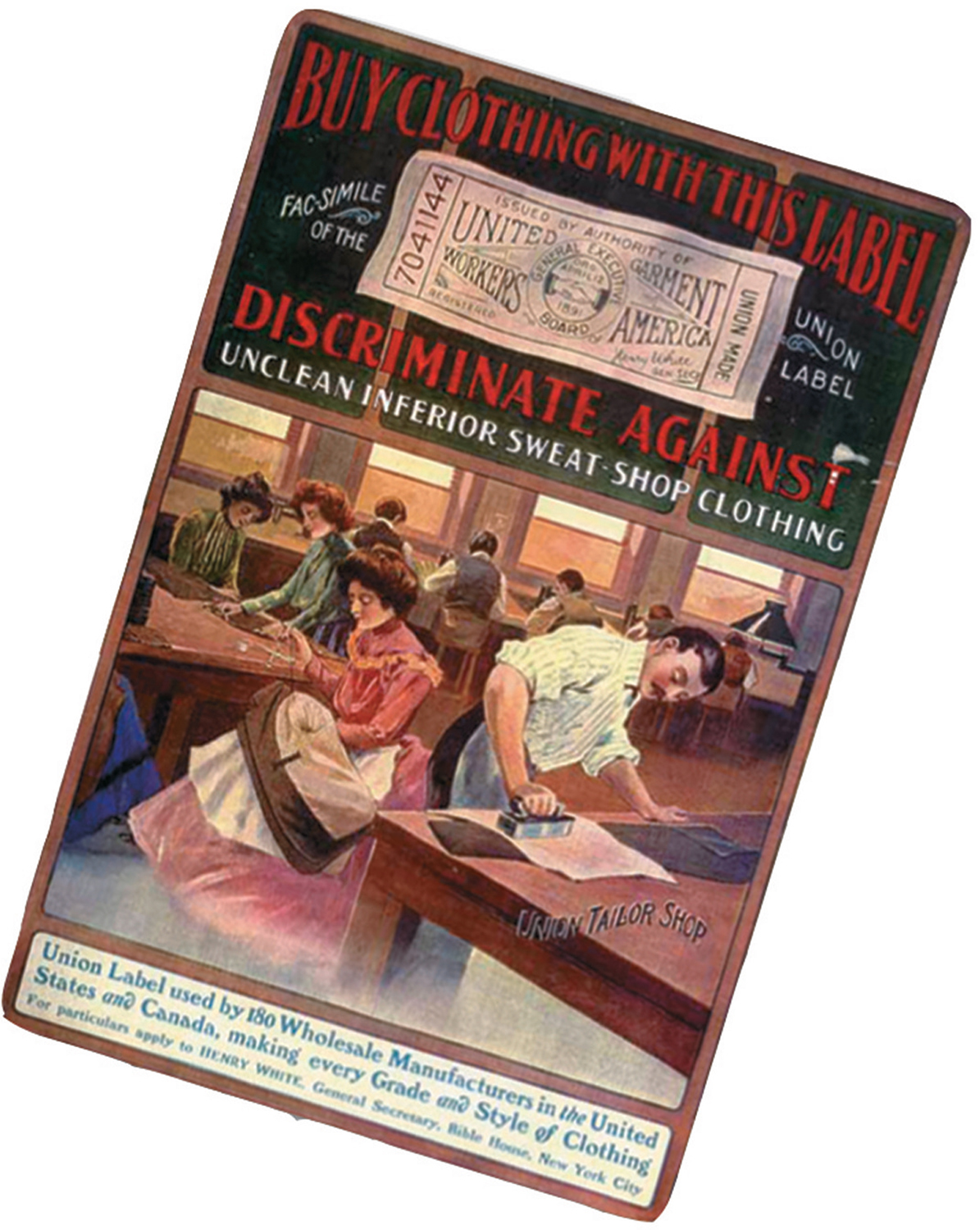

The National Consumers League (NCL) also fostered cross-

Advocates of protective legislation had won a major victory in 1908 when the U.S. Supreme Court, in Muller v. Oregon, reversed its previous rulings and upheld an Oregon law that limited to ten the number of hours women could work in a day. A mass of sociological evidence put together by Florence Kelley of the NCL and Josephine Goldmark of the WTUL convinced the Court that long hours endangered women and therefore the entire human race. The Court’s ruling set a precedent, but one that separated the well-

Reform also fueled the fight for woman suffrage. For women like Jane Addams, involvement in social reform led inevitably to support for woman suffrage. These new suffragists emphasized the reforms that could be accomplished if women had the vote. Addams insisted that in an urban, industrial society, a good housekeeper could not be sure the food she fed her family, or the water and milk they drank, were pure unless she could vote.

REVIEW What types of people were drawn to the progressive movement, and why?