The Progressive Stake in the War

Progressives embraced the idea that the war could be an agent of national improvement. The Wilson administration, realizing that the federal government would have to assert greater control to mobilize the nation’s human and physical resources, created new agencies to manage the war effort. Bernard Baruch, a Wall Street stockbroker, headed the War Industries Board, charged with stimulating and directing industrial production. Baruch brought industrial management and labor together into a team that produced everything from boots to bullets and made U.S. troops the best-

Herbert Hoover, a self-

Wartime agencies multiplied: The Railroad Administration directed railroad traffic, the Fuel Administration coordinated the coal industry and other fuel suppliers, the Shipping Board organized the merchant marine, and the National War Labor Policies Board resolved labor disputes. Their successes gave most progressives reason to believe that, indeed, war and reform marched together.

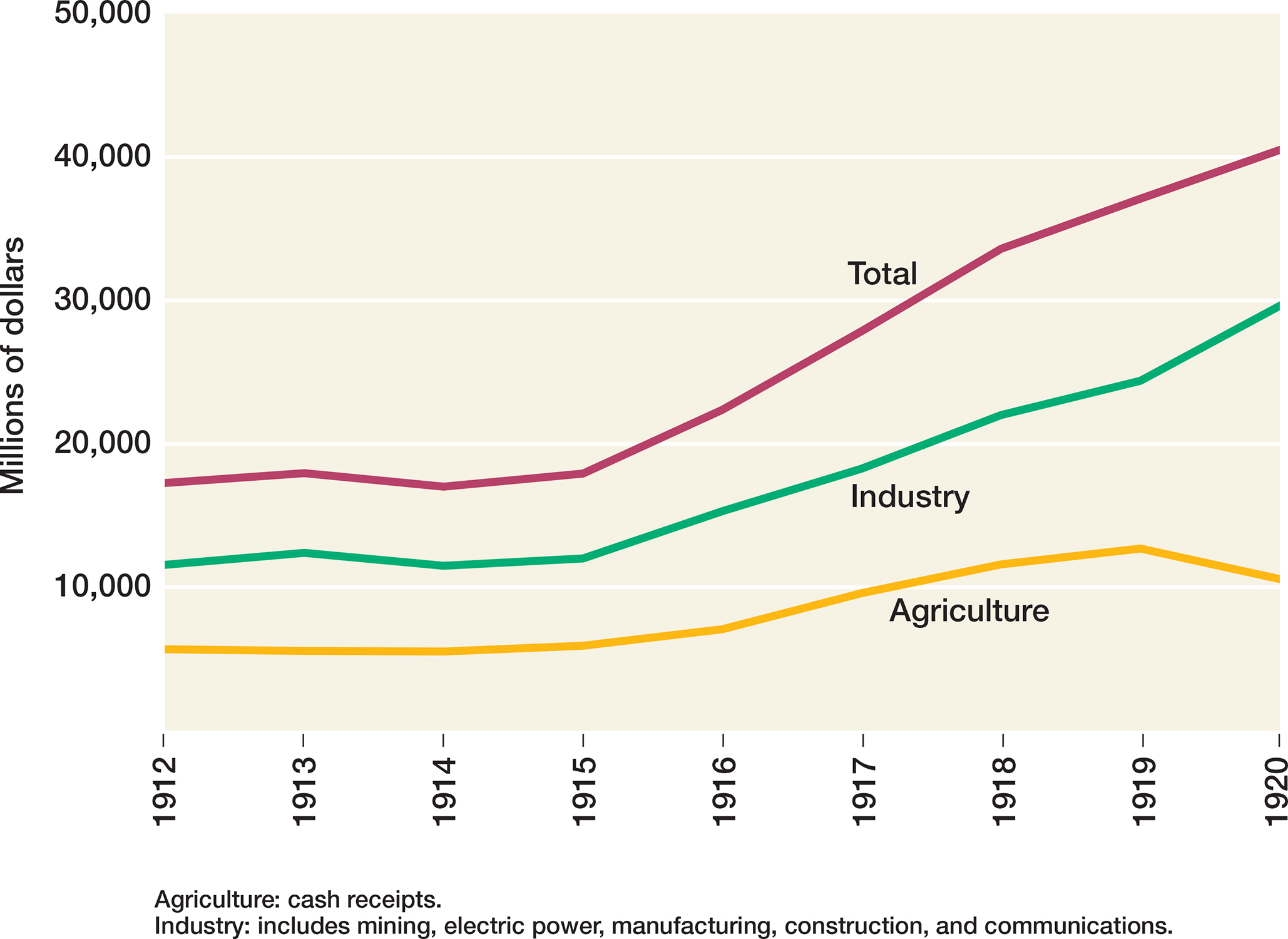

Industrial leaders found that wartime agencies enforced efficiency, which helped corporate profits triple. Some working people also had cause to celebrate. Mobilization meant high prices for farmers and plentiful jobs at high wages in the new war industries (Figure 22.2). Because increased industrial production required peaceful labor relations, the National War Labor Policies Board enacted the eight-

The war also provided a huge boost to the crusade to ban alcohol. By 1917, prohibitionists had convinced nineteen states to go dry. Liquor’s opponents now argued that banning alcohol would make the cause of democracy powerful and pure. At the same time, shutting down the distilleries would save millions of bushels of grain that could feed the United States and its allies. “Shall the many have food or the few drink?” the drys asked. Prohibition received an additional boost because many of the breweries had German names—