Rally Around the Flag—or Else

When Congress committed the nation to war, only a handful of peace advocates resisted the tide of patriotism. A group of professional women, led by settlement house leader Jane Addams and economics professor Emily Greene Balch, denounced what Addams described as “the pathetic belief in the regenerative results of war.” After America entered the conflict, advocates for peace were labeled cowards and traitors.

To suppress criticism of the war, Wilson stirred up patriotic fervor. In 1917, the president created the Committee on Public Information under the direction of George Creel, a journalist who became the nation’s cheerleader for war. Creel sent “Four-

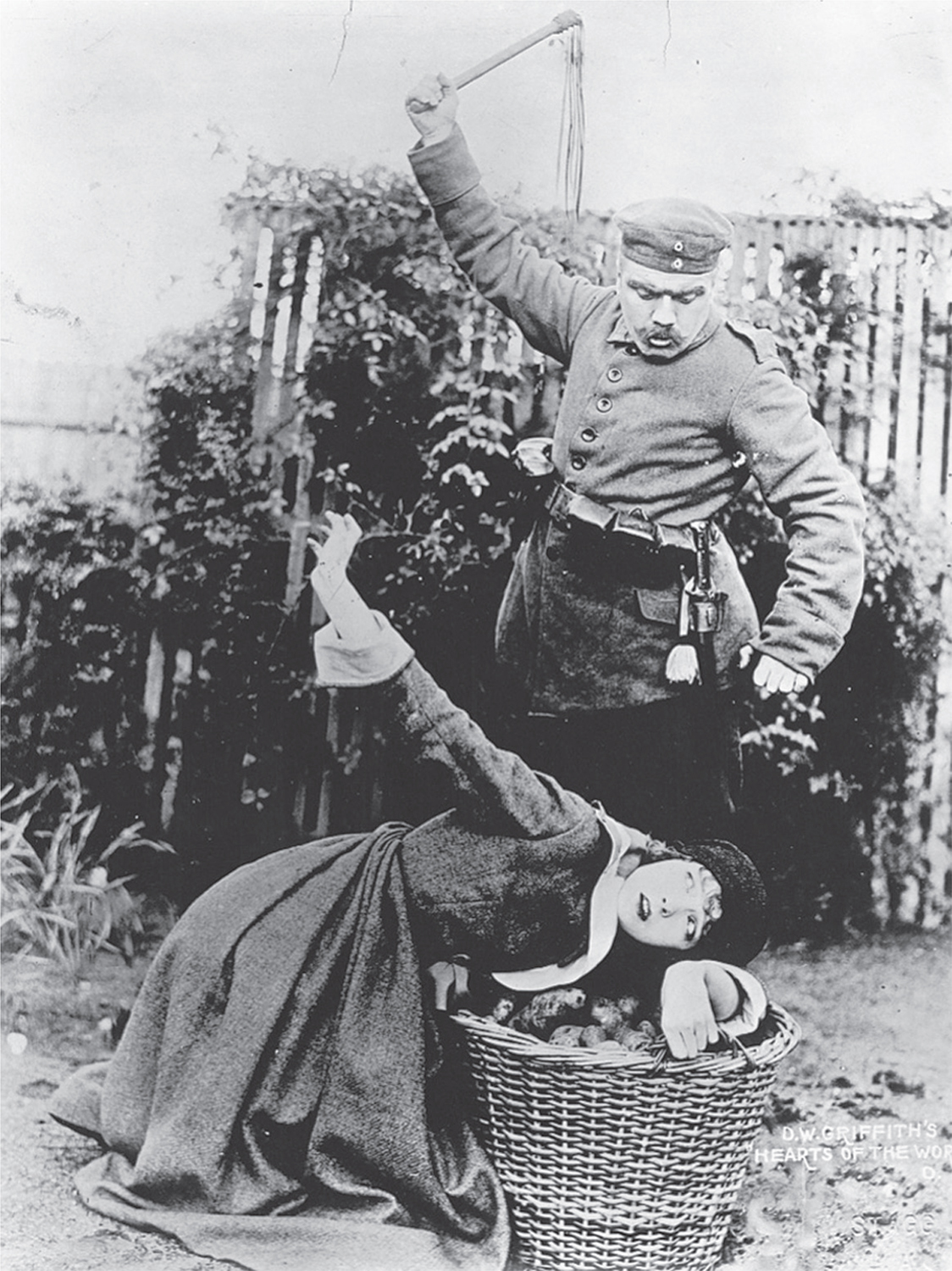

America rallied around Creel’s campaign. The film industry cranked out pro-

A firestorm of anti-

As hysteria increased, the campaign reached absurd levels. Menus across the nation changed German toast to French toast and sauerkraut to liberty cabbage. In Milwaukee, vigilantes mounted a machine gun outside the Pabst Theater to prevent the staging of Schiller’s Wilhelm Tell, a powerful protest against tyranny. The fiancée of one of the war’s leading critics, caught dancing on the dunes of Cape Cod, was held on suspicion of signaling to German submarines.

The Wilson administration’s zeal in suppressing dissent contrasted sharply with its war aims of defending democracy. In the name of self-

One of them was Eugene V. Debs, the leader of the Socialist Party, who was convicted under the Espionage Act and sentenced to ten years. In a speech on June 16, 1918, Debs declared that the United States was not fighting a noble war to make the world safe for democracy but had joined greedy European imperialists seeking to conquer the globe. The government claimed that Debs had crossed the line between legitimate dissent and criminal speech. From the Atlanta penitentiary, Debs argued that he was just telling the truth, like hundreds of his friends who were also in jail.

The president hoped that national commitment to the war would silence partisan politics, but his Republican rivals used the war as a weapon against the Democrats. The trick was to oppose Wilson’s conduct of the war but not the war itself. Republicans outshouted Wilson on the nation’s need to mobilize for war but then complained that Wilson’s War Industries Board was a tyrannical agency that crushed free enterprise. As the war progressed, Republicans gathered power against the Democrats, who had narrowly reelected Wilson in 1916.

In 1918, Republicans gained a narrow majority in both the House and the Senate. The end of Democratic control of Congress not only halted further domestic reform but also meant that the United States would advance toward military victory in Europe with political power divided between a Democratic president and a Republican Congress likely to challenge Wilson’s plans for international cooperation.

REVIEW How did progressive ideals fare during wartime?