Taming the Americas

When he took office, Wilson sought to distinguish his foreign policy from that of his Republican predecessors. To Wilson, Theodore Roosevelt’s “big stick” and William Howard Taft’s “dollar diplomacy” appeared as crude flexing of military and economic muscle. To signal a new direction, Wilson appointed William Jennings Bryan, a pacifist, as secretary of state.

But Wilson and Bryan, like Roosevelt and Taft, also believed that the Monroe Doctrine gave the United States special rights and responsibilities in the Western Hemisphere. Issued in 1823 to warn Europeans not to attempt to colonize the Americas again, the doctrine had become a cloak for U.S. domination. Wilson thus authorized U.S. military intervention in Nicaragua, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic, paving the way for U.S. banks and corporations to take financial control. All the while, Wilson believed that U.S. actions were promoting order and democracy. “I am going to teach the South American Republics to elect good men!” he declared (Map 22.1).

Wilson’s most serious involvement in Latin America came in Mexico. When General Victoriano Huerta seized power by violent means in 1913, most European nations promptly recognized Mexico’s new government, but Wilson refused, declaring that he would not support a “government of butchers.” In April 1914, Wilson sent 800 Marines to seize the port of Veracruz to prevent the unloading of a large shipment of arms for Huerta. Huerta fled to Spain, and the United States welcomed a more compliant government.

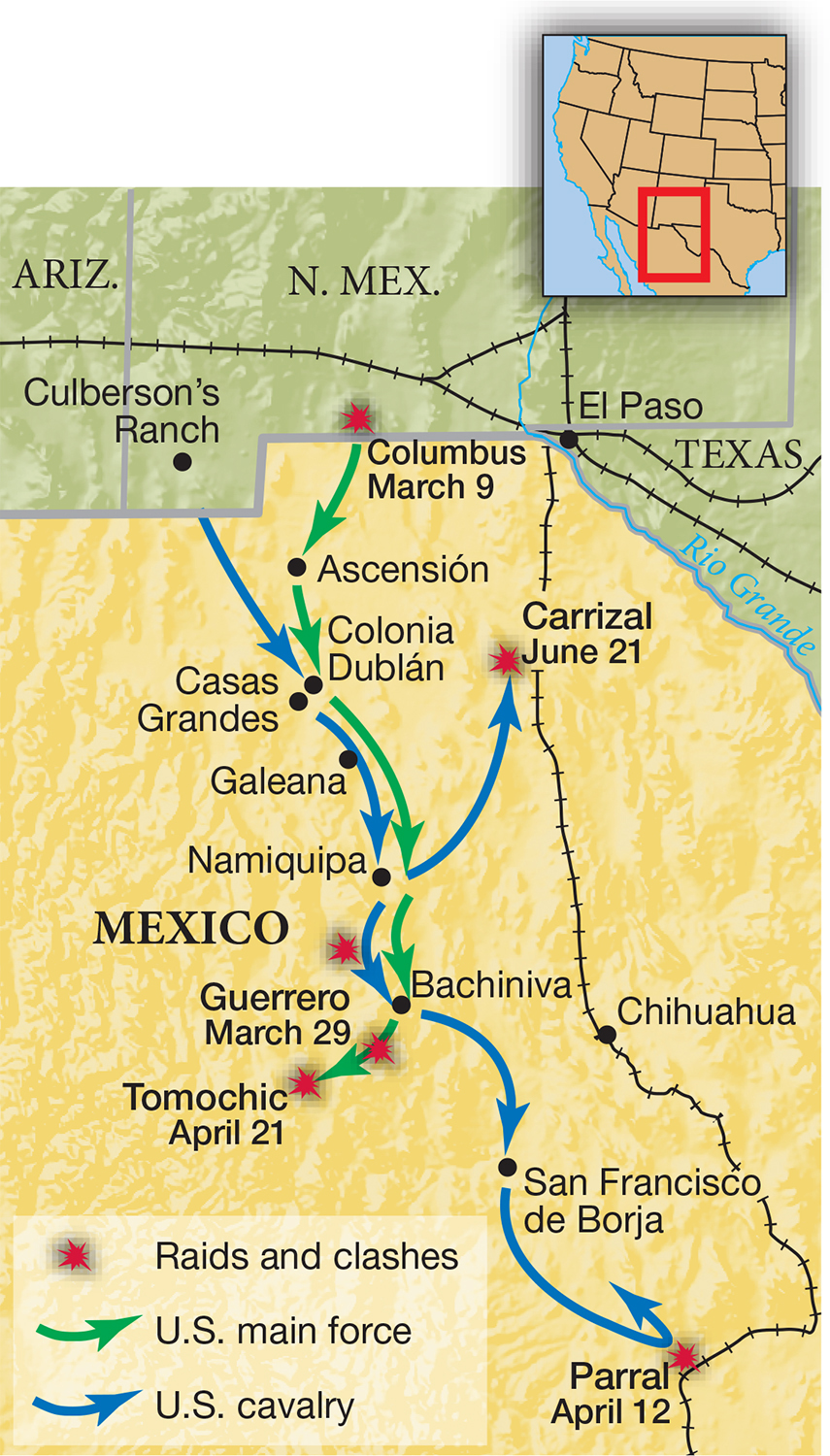

But a rebellion erupted among desperately poor farmers who believed that the new government, aided by U.S. business interests, had betrayed the revolution’s promise to help the common people. In January 1916, the rebel army, commanded by Francisco “Pancho” Villa, seized a train carrying gold to Texas from an American-