The New Woman

Of all the changes in American life in the 1920s, none sparked more heated debate than the alternatives offered to the traditional roles of women. Increasing numbers of women worked and went to college, defying older gender norms. Even mainstream magazines such as the Saturday Evening Post began publishing stories about young, college-

When the Nineteenth Amendment, ratified in 1920, granted women the vote, feminists felt liberated and expected women to reshape the political landscape. A Kansas woman declared, “I went to bed last night a slave[;] I awoke this morning a free woman.” Women began pressuring Congress to pass laws that especially concerned women, including measures to protect women in factories and grant federal aid to schools. Black women lobbied particularly for federal courts to assume jurisdiction over the crime of lynching. But women’s only significant national legislative success came in 1921 when Congress enacted the Sheppard-

A number of factors helped thwart women’s political influence. Male domination of both political parties, the rarity of female candidates, and lack of experience in voting, especially among recent immigrants, kept many women away from the polls. In some places, male-

Most important, rather than forming a solid voting bloc, feminists divided. Some argued for women’s right to special protection; others demanded equal protection. The radical National Woman’s Party fought for an Equal Rights Amendment that stated flatly: “Men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States.” The more moderate League of Women Voters feared that the amendment’s wording threatened state laws that provided women special protection, such as preventing them from working on certain machines. Put before Congress in 1923, the Equal Rights Amendment went down to defeat, and radical women were forced to work for the causes of birth control, legal equality for minorities, and the end of child labor through other means.

Economically, more women worked for pay—

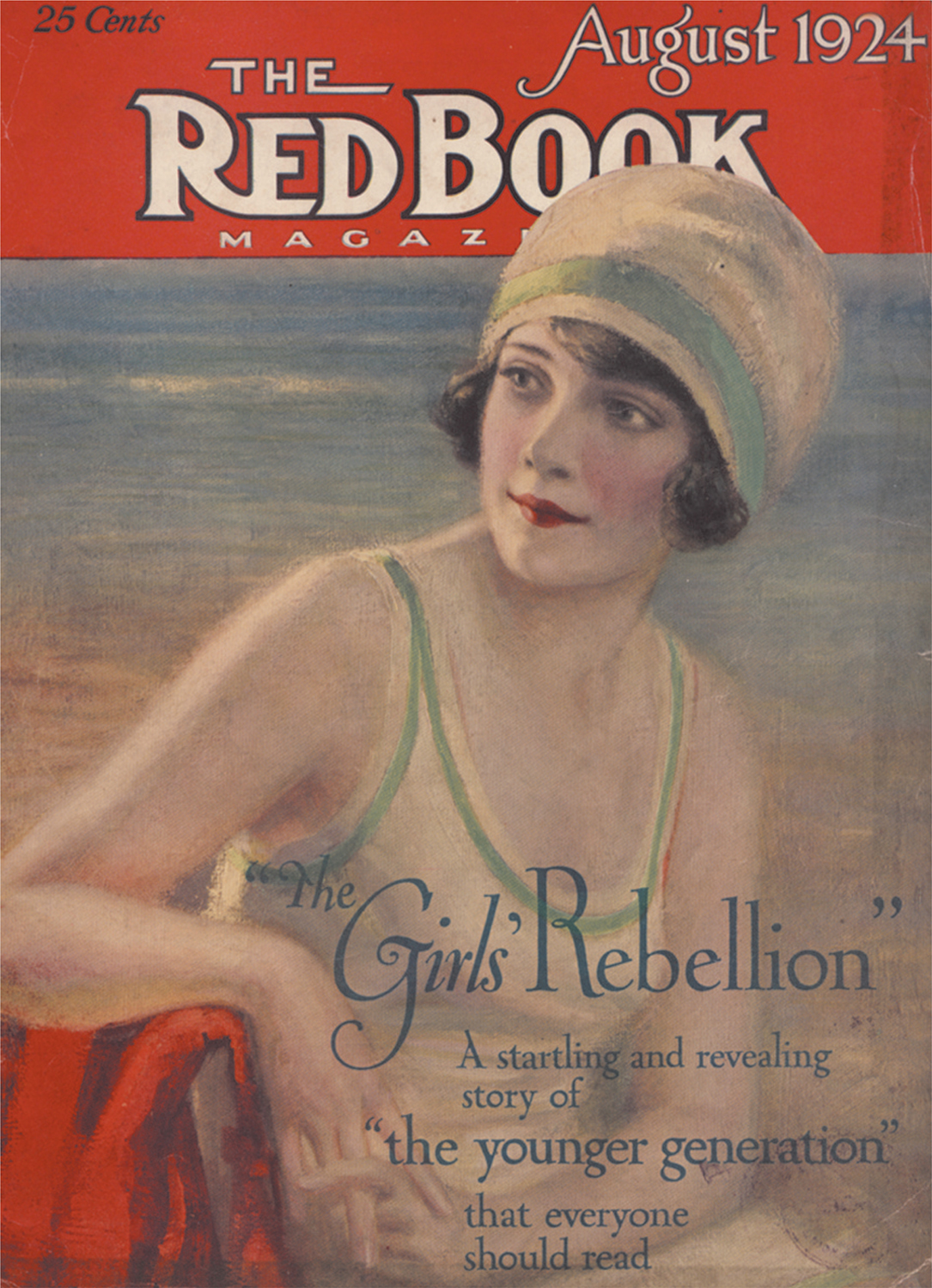

Increased earnings gave working women more buying power in the new consumer culture. A stereotype soon emerged of the flapper, so called because of the short-

The new woman both reflected and propelled the modern birth control movement. Margaret Sanger, the crusading pioneer for contraception during the Progressive Era (see “Radical Alternatives” in chapter 21), restated her principal conviction in 1920: “No woman can call herself free until she can choose consciously whether she will or will not be a mother.” By shifting strategy in the twenties, Sanger courted the conservative American Medical Association; linked birth control with the eugenics movement, which advocated limiting reproduction among “undesirable” groups; and thus made contraception a respectable subject for discussion.

Flapper style and values spread from coast to coast through films, novels, magazines, and advertisements. New women challenged American convictions about separate spheres for women and men, the double standard of sexual conduct, and Victorian ideas of proper female appearance and behavior. (See “Historical Question.”) Although only a minority of American women became flappers, all women, even those who remained at home, heard about girls gone wild and felt the great changes of the era.