Building a National Security State

During the Truman years, advocates of the new containment policy fashioned a six-

In September 1949, the Soviet Union detonated its own atomic bomb, ending the U.S. monopoly on atomic weapons. Truman then approved the development of a hydrogen bomb—

From the 1950s through the 1980s, deterrence formed the basis of American nuclear strategy. To deter a Soviet attack, the United States strove to maintain a nuclear force more powerful than that of the Soviets. Because the Russians pursued a similar policy, the superpowers became locked in an ever-

Implementing the second component of containment, the United States beefed up its conventional military power to deter Soviet threats that might not warrant nuclear retaliation. The National Security Act of 1947 united the military branches under a single secretary of defense and created the National Security Council (NSC) to advise the president. During the Berlin crisis in 1948, Congress hiked military appropriations and enacted a peacetime draft. In addition, Congress granted permanent status to the women’s military branches, though it limited their numbers, the jobs they could do, and the rank female servicemembers could attain. With 1.5 million men and women in uniform in 1950, the military strength of the United States had quadrupled since the 1930s, and defense expenditures claimed one-

Collective security, the third prong of containment strategy, marked a sharp reversal of the nation’s traditional foreign policy. In 1949, the United States joined Canada and Western European nations in its first peacetime military alliance, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), designed to counter a Soviet threat to Western Europe (see Map 26.1). For the first time in its history, the United States pledged to go to war if one of its allies was attacked.

The fourth element of defense strategy provided foreign assistance programs to strengthen friendly countries, such as aid to Greece and Turkey and the Marshall Plan. In addition, in 1949 Congress approved $1 billion of military aid to its NATO allies, and the government began economic assistance to nations in other parts of the world.

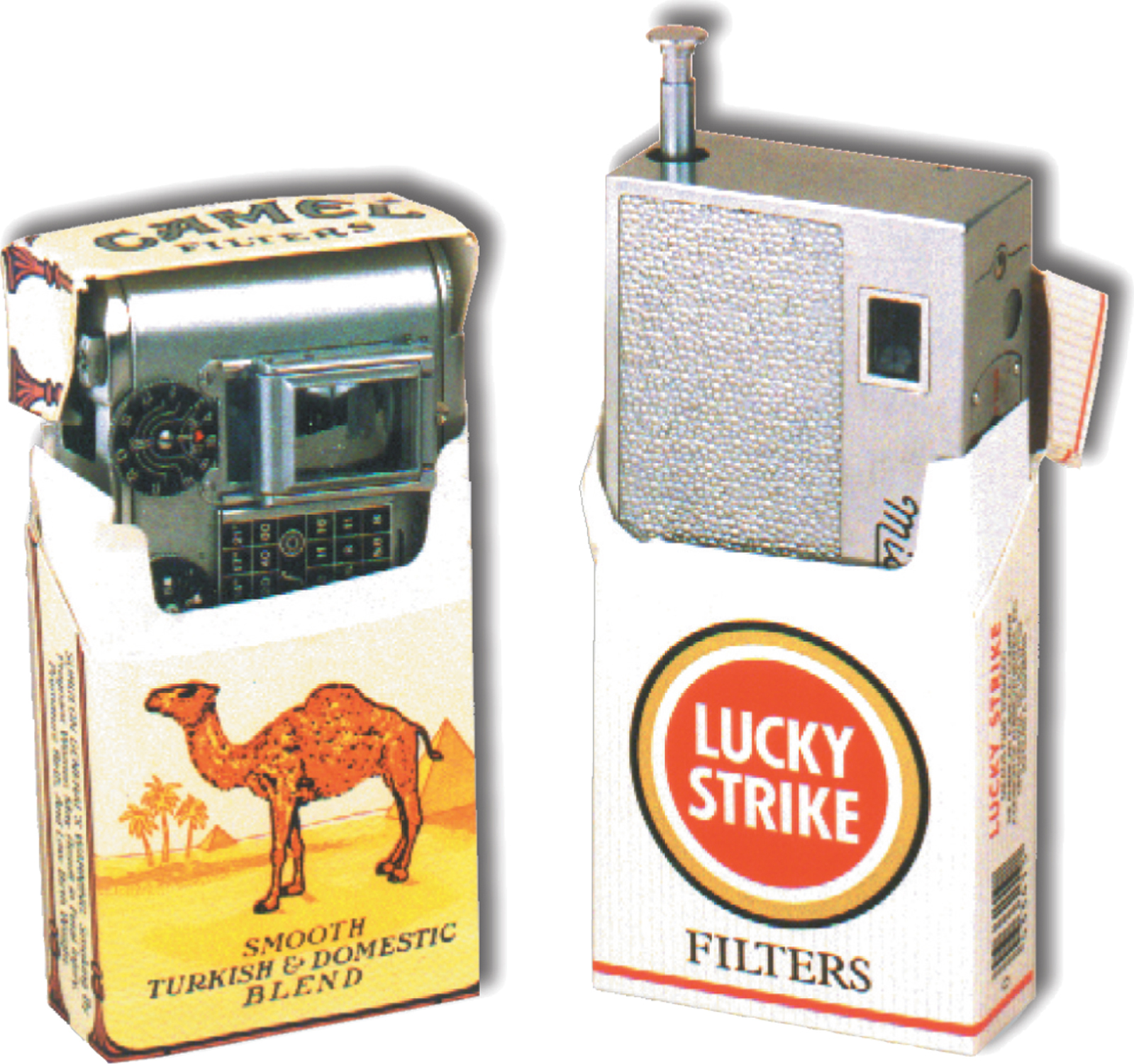

The fifth ingredient of containment improved the government’s capacity to thwart communism through espionage and covert activities. The National Security Act of 1947 created the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to gather information and to perform any activities “related to intelligence affecting the national security” that the NSC might authorize. Such functions included propaganda, sabotage, economic warfare, and support for “anti-

Finally, the U.S. government created cultural exchanges and propaganda to win “hearts and minds” throughout the world. The Voice of America, established during World War II to broadcast U.S. propaganda abroad, expanded, and the State Department sent books, exhibits, jazz musicians, and other performers to foreign countries as “cultural ambassadors.”

By 1950, the United States had abandoned age-