The Domestic Chill: McCarthyism

Truman’s domestic agenda also suffered from a wave of anticommunism that weakened liberals. “Red-baiting” (attempting to link individuals or ideas with communism) and official retaliation against leftist critics of the government had flourished during the Red scare at the end of World War I (see “The Red Scare” in chapter 22), and Republicans had attacked the New Deal as a plot of radicals. A second Red scare followed World War II, born of partisan politics, the collapse of the Soviet-American alliance, foreign policy setbacks, and disclosures of Soviet espionage.

Republicans jumped on events such as the Soviet takeover of Eastern Europe and the Communist triumph in China to accuse Democrats of fostering internal subversion. Wisconsin senator Joseph R. McCarthy avowed that “the Communists within our borders have been more responsible for the success of Communism abroad than Soviet Russia.” McCarthy’s charges—such as the allegation that retired general George C. Marshall belonged to a Communist conspiracy—were reckless and often ludicrous, but the press covered him avidly, and McCarthyism became a term synonymous with the anti-Communist crusade.

Revelations of Soviet espionage lent credibility to fears of internal communism. A number of ex-Communists, including Whittaker Chambers and Elizabeth Bentley, testified that they and others had provided secret documents to the Soviets. Most alarming of all, in 1950 a British physicist working on the atomic bomb project confessed that he was a spy and implicated several Americans, including Ethel and Julius Rosenberg. The Rosenbergs pleaded not guilty but were convicted of conspiracy to commit espionage and electrocuted in 1953.

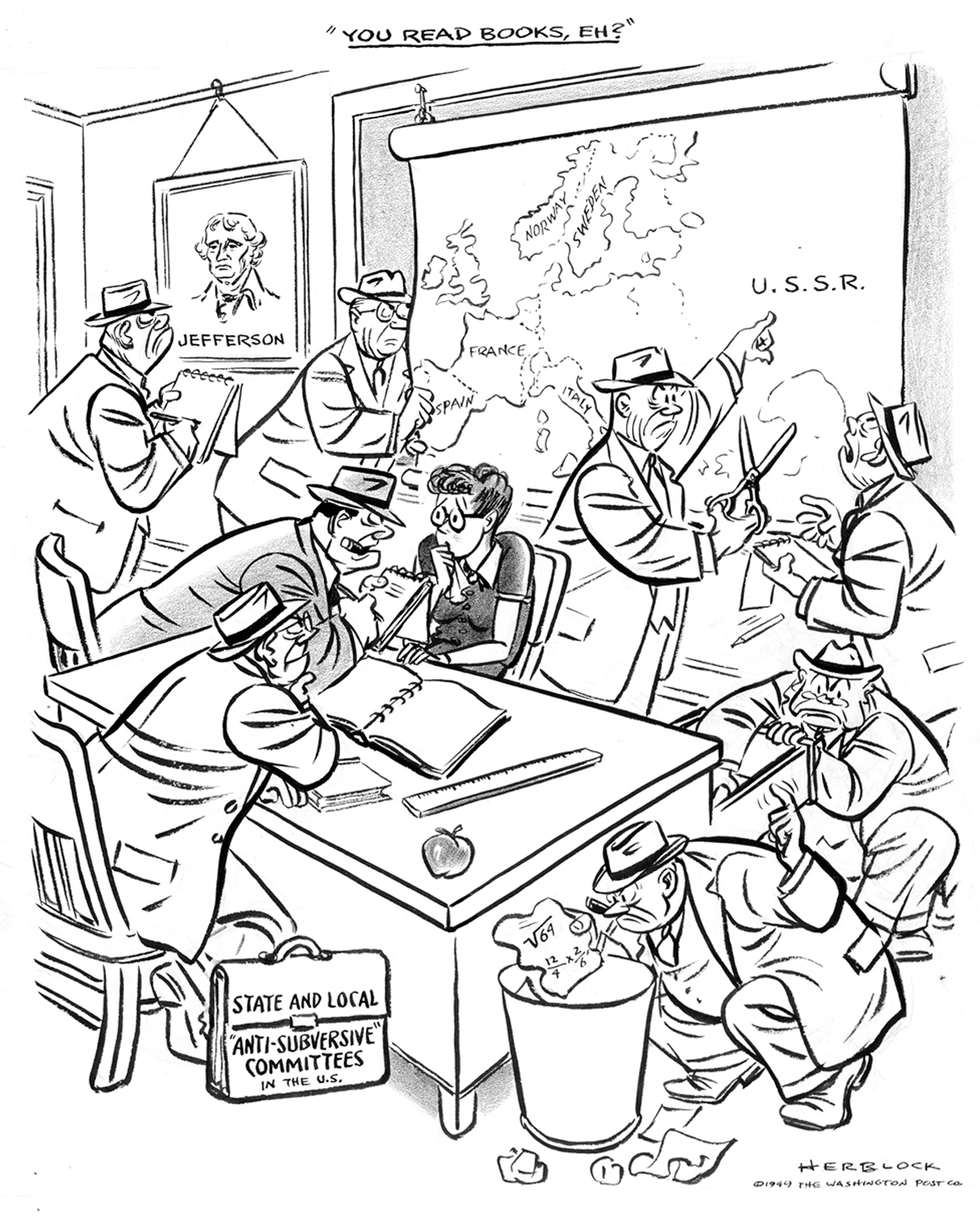

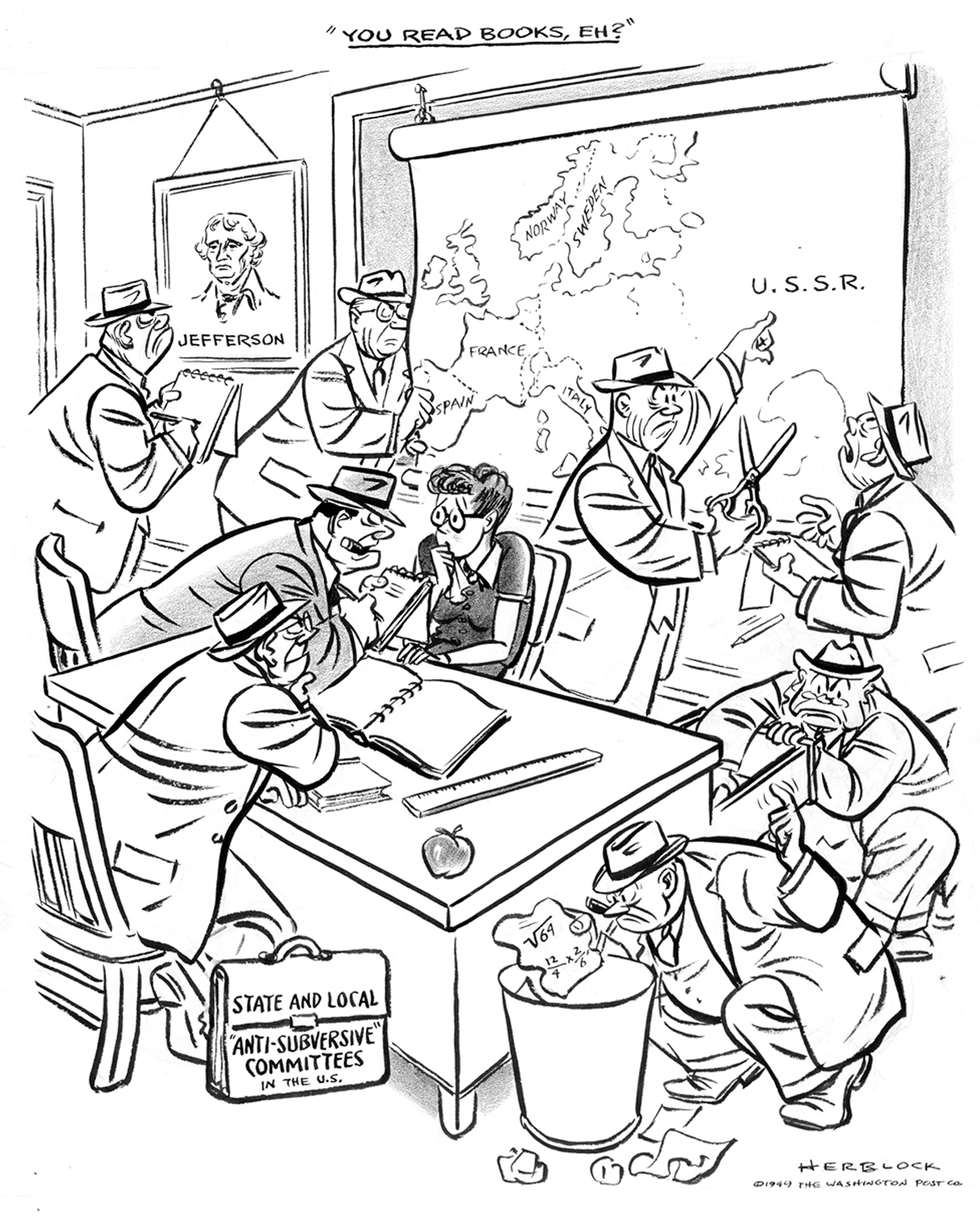

VISUAL ACTIVITY The Red Scare The celebrated editorial cartoonist for the Washington Post, Herbert Lawrence Block, was a frequent critic of McCarthyism. In this 1949 cartoon, he addressed the intimidation of teachers, which occurred across the country in public schools and universities. Public officials demanded that teachers take loyalty oaths, grilled them about their past and present political associations, and fired those who refused to cooperate. A 1949 Herblock Cartoon, © The Herb Block Foundation. READING THE IMAGE: What is the effect of portraying a female teacher and nine hefty male investigators? What does the man with scissors appear to be doing, and how does this ridicule the Red Scare? Do you think it was coincidental that the artist included a portrait of Thomas Jefferson, author of the Bill of Rights? CONNECTIONS: How did the Red scare affect the prospects of Truman’s domestic agenda?

Records opened in the 1990s showed that the Soviet Union did receive secret documents from Americans that probably hastened its development of nuclear weapons by a year or two. Yet the vast majority of individuals hunted down in the Red scare had done nothing more than at one time joining the Communist Party, associating with Communists, or supporting radical causes. And nearly all the accusations related to activities that had taken place long before the Cold War had made the Soviet Union an enemy.

The hunt for subversives was conducted by both Congress and the executive branch. Stung by charges of communism in the 1946 mid-term elections, Truman issued Executive Order 9835 in March 1947, establishing loyalty review boards to investigate every federal employee. “A nightmare from which there [was] no awakening” was how State Department employee Esther Brunauer described it when she and her husband, a chemist in the navy, both lost their jobs because he had joined a Communist youth organization in the 1920s and associated with suspected radicals. Government investigators allowed anonymous informers to make charges and placed the burden of proof on the accused. More than two thousand civil service employees lost their jobs, and another ten thousand resigned as Truman’s loyalty program continued into the mid-1950s. Hundreds of homosexuals resigned or were fired over charges of “sexual perversion,” which anti-Communist crusaders said could subject them to blackmail. Years later, Truman said privately that the loyalty program had been a mistake.

Congressional committees, such as the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), also investigated individuals’ political associations. When those under scrutiny refused to name names, investigators charged that silence was tantamount to confession, and these “unfriendly witnesses” lost their jobs and suffered public ostracism. In 1947, HUAC investigated radical activity in Hollywood. Some actors and directors cooperated, but ten refused, citing their First Amendment rights. The “Hollywood Ten” served jail sentences for contempt of Congress—a punishment that Helen Gahagan Douglas fought—and then found themselves blacklisted in the movie industry.

The Truman administration went after the Communist Party directly, prosecuting its leaders under a 1940 law that made it a crime to “advocate the overthrow and destruction of the [government] by force and violence.” Although civil libertarians argued that the guilty verdicts violated First Amendment freedoms of speech, press, and association, the Supreme Court ruled in 1951 that the Communist threat overrode constitutional guarantees.

The domestic Cold War spread beyond the nation’s capital. State and local governments investigated citizens, demanded loyalty oaths, fired employees suspected of disloyalty, banned books from public libraries, and more. College professors and public school teachers lost their jobs in New York, California, and elsewhere. (See “Seeking the American Promise.”) Because the Communist Party had helped organize unions and championed racial justice, labor and civil rights activists fell prey to McCarthyism as well. African American activist Jack O’Dell remembered that segregationists pinned the tag of Communist on “anybody who supported the right of blacks to have civil rights.”

McCarthyism caused untold harm to thousands of innocent individuals. Anti-Communist crusaders humiliated and discredited law-abiding citizens, hounded them from their jobs, and in some cases even sent them to prison. The anti-Communist crusade violated fundamental constitutional rights of freedom of speech and association and stifled the expression of dissenting ideas or unpopular causes.

REVIEW Why did Truman have limited success in implementing his domestic agenda?