Korea, Communism, and the 1952 Election

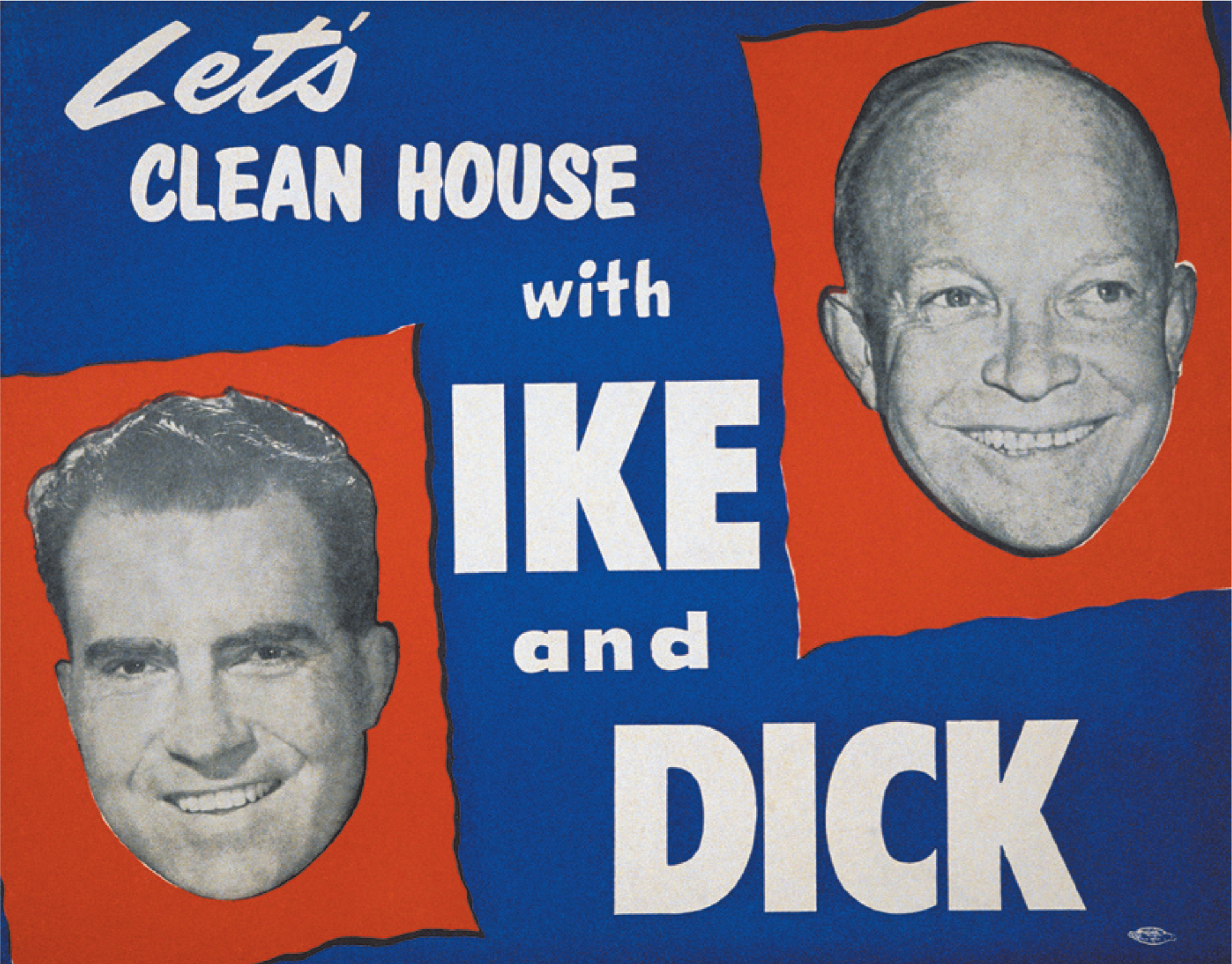

Popular discontent with Truman’s war boosted Republicans in the 1952 election. Their presidential nominee, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, was a popular hero. As supreme commander in Europe, he won widespread acclaim for leading the Allied armies to victory over Germany in World War II, and in 1950 Truman appointed Eisenhower the first supreme commander of NATO forces.

Although Eisenhower believed that professional soldiers should stay out of politics, he found compelling reasons to run in 1952. He largely agreed with Truman’s foreign policy, but he deplored the Democrats’ propensity to solve domestic problems with costly new federal programs. He also disliked the foreign policy views of leading Republican presidential contender, Senator Robert A. Taft, who attacked containment and sought to cut defense spending. Eisenhower defeated Taft for the nomination, but the old guard prevailed on the party platform. It excoriated containment as “negative, futile, and im-

Richard Milhous Nixon grew up in southern California, worked his way through college and law school, served in the navy, and briefly practiced law, before winning election to Congress in 1946. Nixon quickly made a name for himself as a member of HUAC (see page 761) and a key anti-

With his public approval ratings plummeting, Truman decided not to run for reelection. The Democrats nominated Adlai E. Stevenson, the popular governor of Illinois, but he could not escape the domestic fallout from the Korean War, nor match Eisenhower’s widespread appeal. Shortly before the election, Eisenhower announced dramatically, “I shall go to Korea,” and voters registered their confidence in his ability to end the war. Cutting sharply into traditional Democratic territory, Eisenhower won several southern states and garnered 55 percent of the popular vote overall. His coattails carried a narrow Republican majority to Congress.