Visualizing History: “School Desegregation”

One of the best-

In 1963, Rockwell parted company with the Post, which had begun to favor pictures of celebrities over Rockwell’s common-

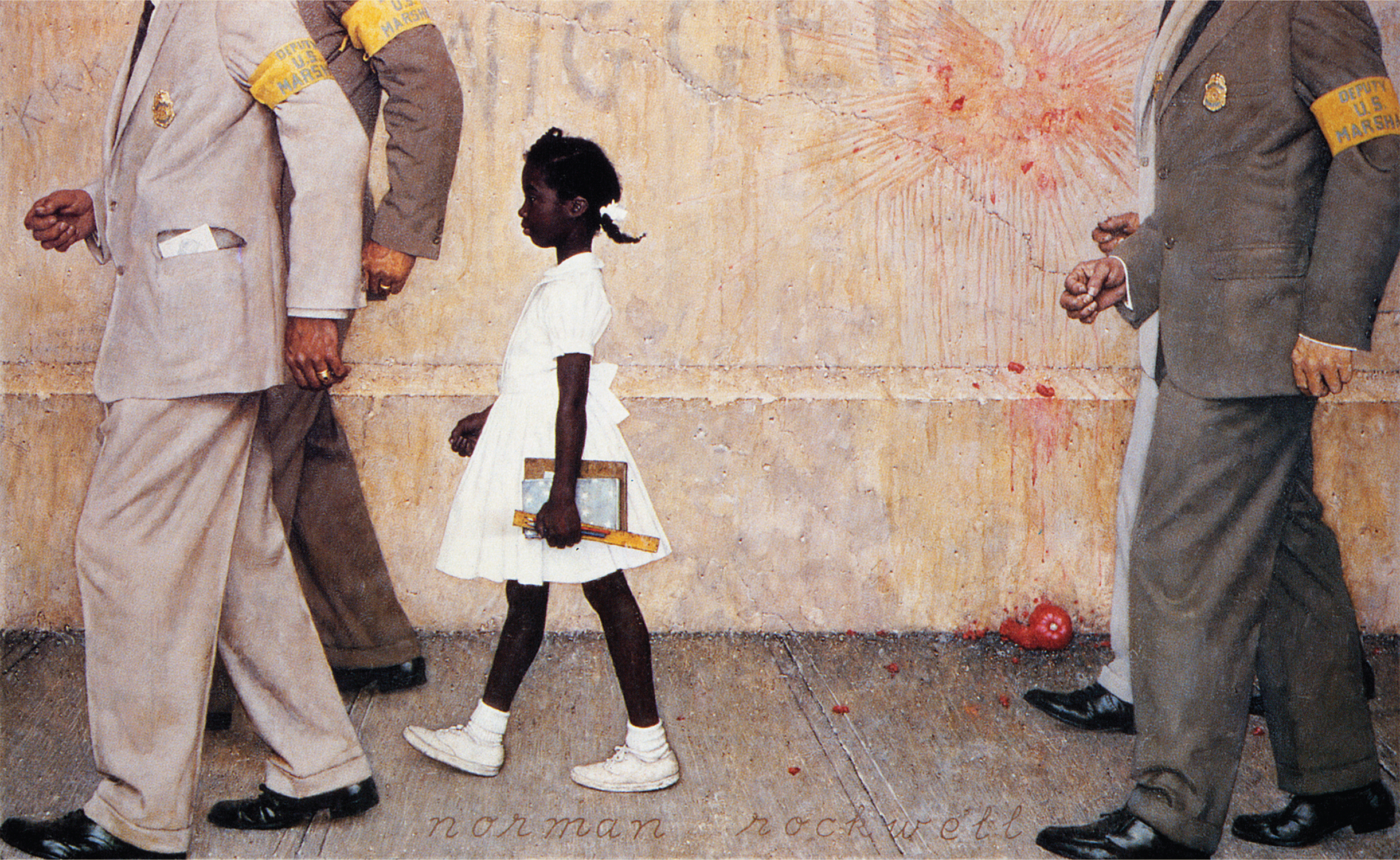

The oil painting captured one moment in the tortured process of school desegregation. After six years of resistance to Brown, the New Orleans school board reluctantly began integration of its schools in 1960, starting with the first grade, with just two schools, and with only a handful of black children. Encouraged by the local NAACP, three African American girls enrolled in one school, and Ruby Bridges, the subject of Rockwell’s painting, was sent to another all-

Rockwell’s painting compels the viewer to focus on young Ruby, who is placed near the center of the piece, a small, solitary figure. She appears dressed in her Sunday best, carrying her school supplies and a posture of determination. While a news photograph showed her dressed in a plaid dress and black shoes, Rockwell painted her clothed in all white. Why might he have taken liberties with reality, and what does his use of the color white for her clothes convey to the viewer?

With the marshals headless and dressed in neutral colors, viewers’ eyes are drawn to Ruby, to the tomatoes splattered on the wall and ground, and to the word written on the wall. Why do you think Rockwell used inanimate objects to depict the screaming mob? Notice that something is sticking out of the first marshal’s pocket, most likely the federal court order that ordered New Orleans to comply with the Brown decision. What is the effect of depicting the scene without the federal marshals’ heads?

Rockwell’s work became an iconic representation of the civil rights movement and hung in the White House in 2011.

SOURCE: Printed by permission of the Norman Rockwell Family Agency. Copyright © 2014 the Norman Rockwell Family Entities.

Questions for Consideration

- What elements in the painting suggest the dangers posed to African Americans who challenged racism?

- Why do you think Rockwell titled his work The Problem We All Live With?

Connect to the Big Idea

What areas of public life, in addition to education, did civil rights activists target in the 1950s?