Termination and Relocation of Native Americans

Eisenhower’s efforts to limit the federal government were consistent with a new direction in Indian policy, which reversed the New Deal emphasis on strengthening tribal governments and preserving Indian culture (see “Neglected Americans and the New Deal” in chapter 24). After World War II, when some 25,000 Indians had left their homes for military service and another 40,000 for work in defense industries, policymakers began to favor assimilating Native Americans and ending their special relationships with the government.

To some officials, who reflected Cold War emphasis on conformity to dominant American values, the communal practices of Indians resembled socialism and stifled individual initiative. Eisenhower’s commissioner of Indian affairs, Glenn Emmons, did not believe that tribal lands could produce income sufficient to eliminate poverty, but he also revealed the ethnocentrism of policymakers when he insisted that Indians wanted to “work and live like Americans.” Moreover, Indians still held rights to water, land, minerals, and other resources that were increasingly attractive to state governments and private entrepreneurs.

By 1960, the government had implemented a three-

The second policy, termination, also originated in the Truman administration when Commissioner Dillon S. Myer asserted that his Bureau of Indian Affairs should do “nothing for Indians which Indians can do for themselves.” Beginning in 1953, Eisenhower signed bills transferring jurisdiction over tribal land to state and local governments and ending the trusteeship relationship between Indians and the federal government. The loss of federal hospitals, schools, and other special arrangements devastated Indian tribes. As had happened after passage of the Dawes Act in 1887 (see “The Dawes Act and Indian Land Allotment” in chapter 17), some corporate interests and individuals took advantage of the opportunity to purchase Indian land cheaply. The government abandoned termination in the 1960s after some 13,000 Indians and more than one million acres of their land had been affected.

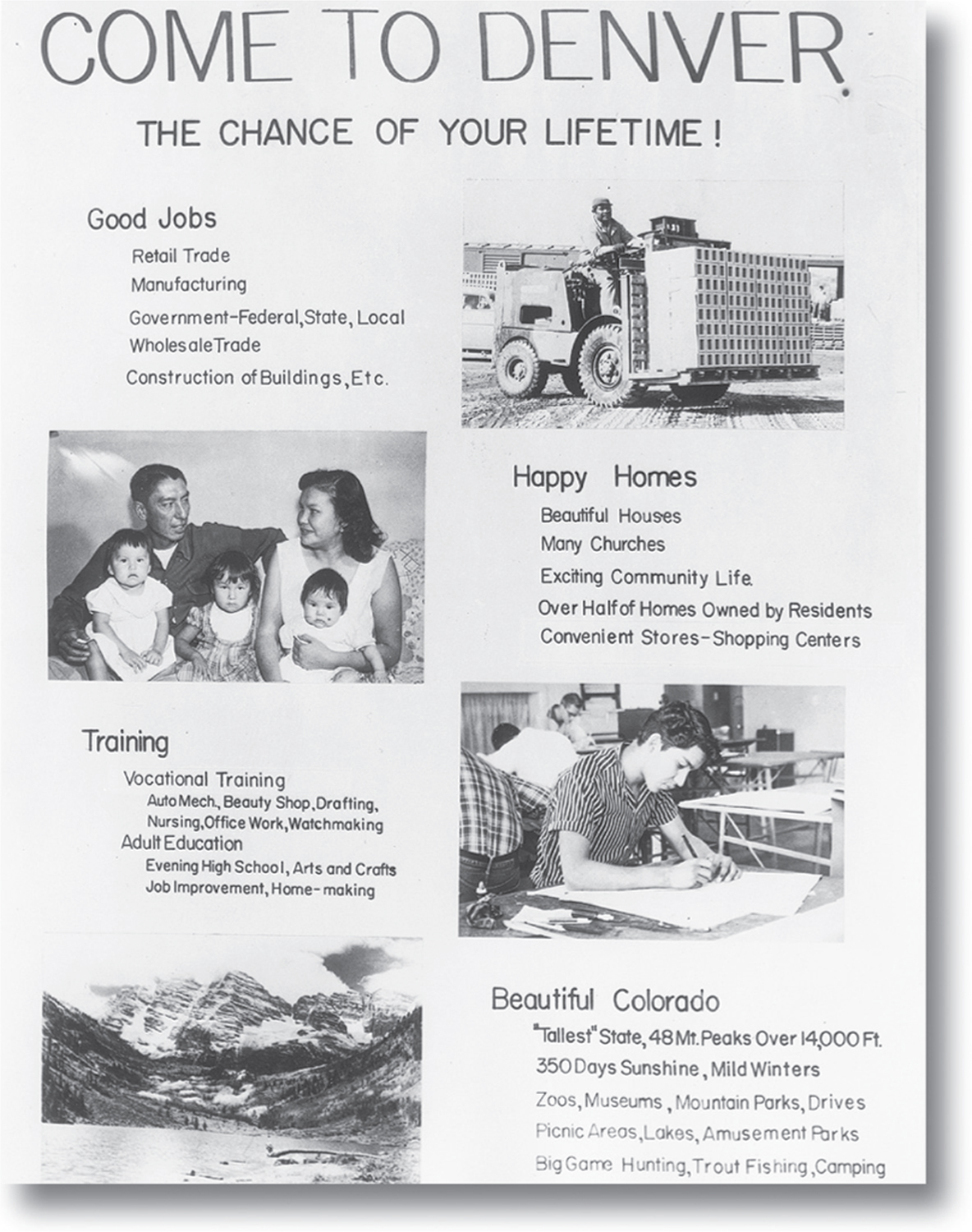

The Indian Relocation Program, the third piece of Native American policy, began in 1948 and involved more than 100,000 Native Americans by 1973. The government encouraged Indians to move to cities, where relocation centers were supposed to help with housing, job training, and medical care. Even though Indians were moved far from their reservations, about one-

Most who stayed in cities faced racism, unemployment, poor housing, and the loss of their traditional culture. “I wish we had never left home,” said one woman whose husband was out of work and drinking heavily. “It’s dirty and noisy, and people all around, crowded. . . .