The Flowering of the Black Freedom Struggle

The Montgomery bus boycott of 1955–

Massive direct action in the South began in February 1960, when four African American college students in Greensboro, North Carolina, requested service at the whites-

In April, Baker helped student activists form a new organization, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Embracing King’s civil disobedience and nonviolence principles, activists would confront their oppressors and stand up for their rights, but they would not respond if attacked. In the words of SNCC leader James Lawson, “Nonviolence nurtures the atmosphere in which reconciliation and justice become actual possibilities.” SNCC, however, rejected the top-

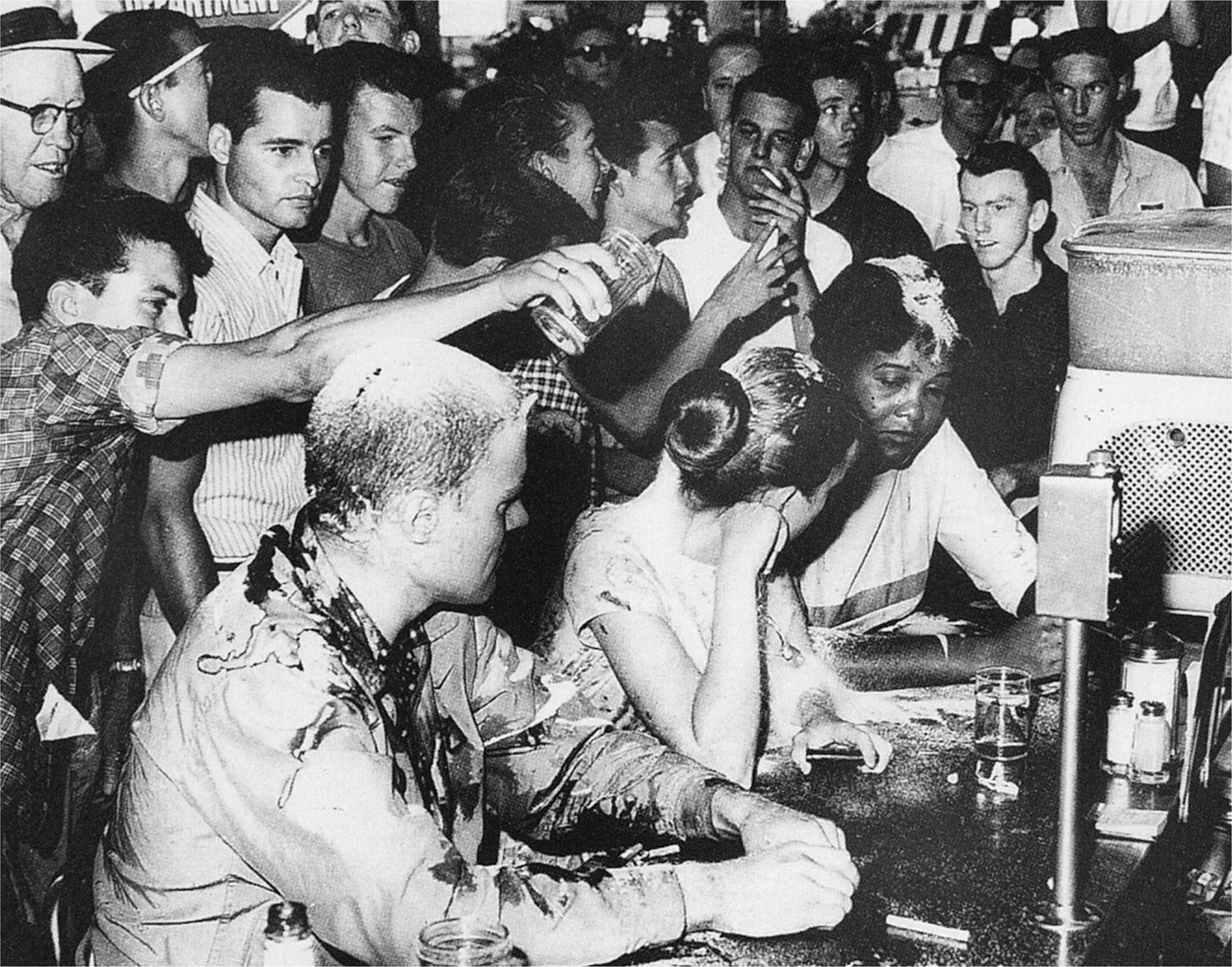

The activists’ optimism and commitment to nonviolence soon underwent severe tests. Although some cities quietly met student demands, more typically activists encountered violence. Hostile whites poured food over demonstrators, burned them with cigarettes, called them “niggers,” and pelted them with rocks. Local police attacked protesters with dogs, clubs, fire hoses, and tear gas, and they arrested thousands of demonstrators.

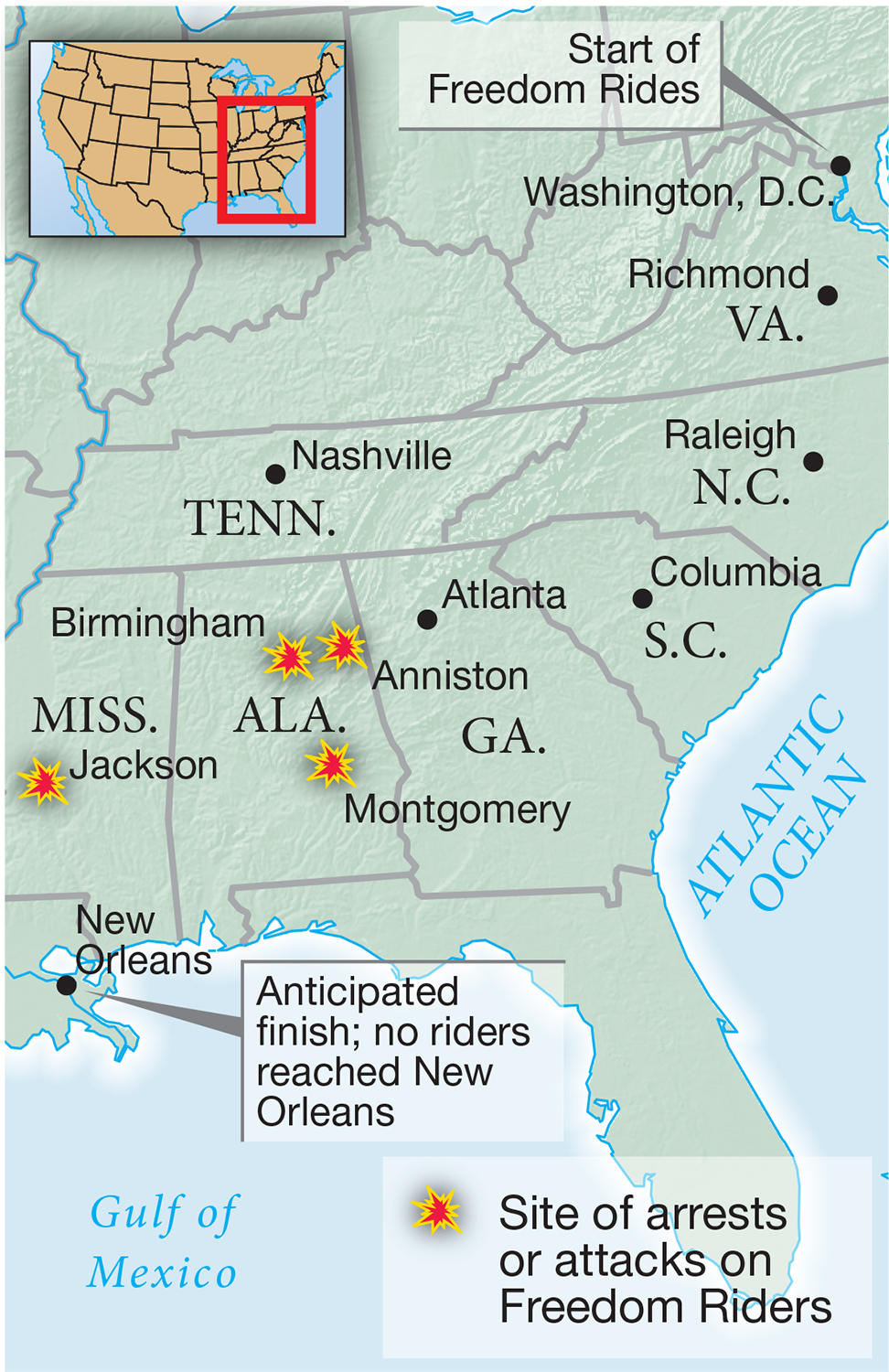

Another wave of protest occurred in May 1961, when the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) organized Freedom Rides to implement Court orders for integrated transportation. When a group of six whites and seven blacks reached Alabama, whites bombed their bus and beat them with baseball bats so fiercely that an observer “couldn’t see their faces through the blood.” CORE rebuffed President Kennedy’s pleas to call off the rides. But after a huge mob attacked the riders in Montgomery, Alabama, Attorney General Robert Kennedy dispatched federal marshals to restore order. Nonetheless, Freedom Riders arriving in Jackson, Mississippi, were promptly arrested, and several hundred spent weeks in jail. All told, more than four hundred blacks and whites participated in the Freedom Rides.

In the summer of 1962, SNCC and other groups began the Voter Education Project to register black voters in southern states. They, too, met violence. Whites bombed black churches, threw tenant farmers out of their homes, and beat and jailed activists such as Fannie Lou Hamer. In June 1963, a white man gunned down Mississippi NAACP leader Medgar Evers in front of his house. Similar violence met King’s 1963 campaign in Birmingham, Alabama, to integrate public facilities and open jobs to blacks. The police attacked demonstrators, including children, with dogs, cattle prods, and fire hoses—

The largest demonstration drew 250,000 blacks and whites to the nation’s capital in August 1963 in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, inspired by the strategy of A. Philip Randolph in 1941 (see “The Double V Campaign” in chapter 25). Speaking from the Lincoln Memorial, King put his indelible stamp on the day. “I have a dream,” he repeated again and again, imagining the day “when all of God’s children . . .

The euphoria of the March on Washington faded as activists returned to face continued violence in the South. In 1964, the Mississippi Freedom Summer Project mobilized more than a thousand northern black and white college students to conduct voter registration drives. Resistance was fierce, and by the end of the summer, only twelve hundred new voters had been allowed to register. Southern whites had killed several activists, beaten eighty, arrested more than a thousand, and burned thirty-

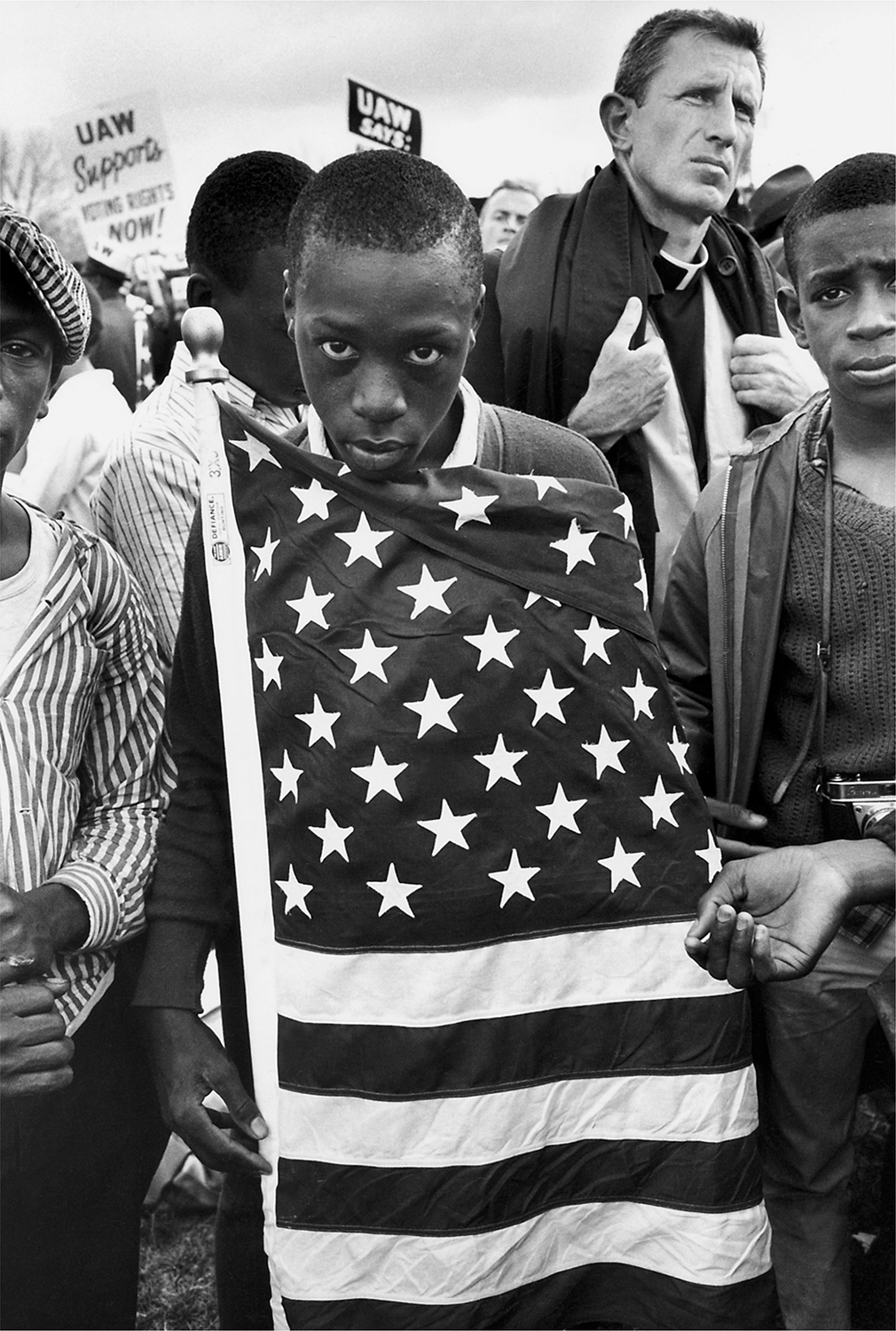

Still, the movement persisted. In March 1965, Alabama state troopers used such violent force to turn back a voting rights march from Selma to the state capitol in Montgomery that the incident earned the name “Bloody Sunday” and compelled President Johnson to call up the Alabama National Guard to protect the marchers. Battered and hospitalized on Bloody Sunday, John Lewis, chairman of SNCC (and later a congressman from Georgia), called the Voting Rights Act, which passed that October, “every bit as momentous as the Emancipation Proclamation.” Referring to the Selma march, he said, “we all felt we’d had a part in it.”