Student Rebellion, the New Left, and the Counterculture

Although materially and legally more secure than their African American, Indian, and Latino counterparts, white youths also expressed dissent, participating in the black freedom struggle, student protests, the antiwar movement, and the new feminist movement. Challenging establishment institutions, young activists were part of a larger international phenomenon of student movements around the globe.

The central organization of white student protest was Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), formed in 1960. In 1962, the organizers wrote in their statement of purpose, “We are people of this generation, bred in at least modest comfort, housed now in universities, looking uncomfortably at the world we inherit.” The idealistic students criticized the complacency of their elders, the remoteness of decision makers, and the powerlessness and alienation generated by a bureaucratic society. SDS aimed to mobilize a “New Left” around the goals of civil rights, peace, and universal economic security. Other forms of student activism soon followed.

The first large-

Hundreds of student rallies and building occupations followed on campuses across the country, especially after 1965, when opposition to the Vietnam War mounted and students protested against universities’ ties with the military (see “The Widening War at Home” in chapter 29). Students also challenged the collegiate environment. Women at the University of Chicago, for example, charged in 1969 that all universities “discriminate against women, impede their full intellectual development, deny them places on the faculty, exploit talented women and mistreat women students.” At Howard University, African American students called for a “Black Awareness Research Institute,” demanding that academic departments “place more emphasis on how these disciplines may be used to effect the liberation of black people.” Across the country, students won curricular reforms such as black studies and women’s studies programs, more financial aid for minority and poor students, independence from paternalistic rules, and a larger voice in campus decision making. (See “Documenting the American Promise.”)

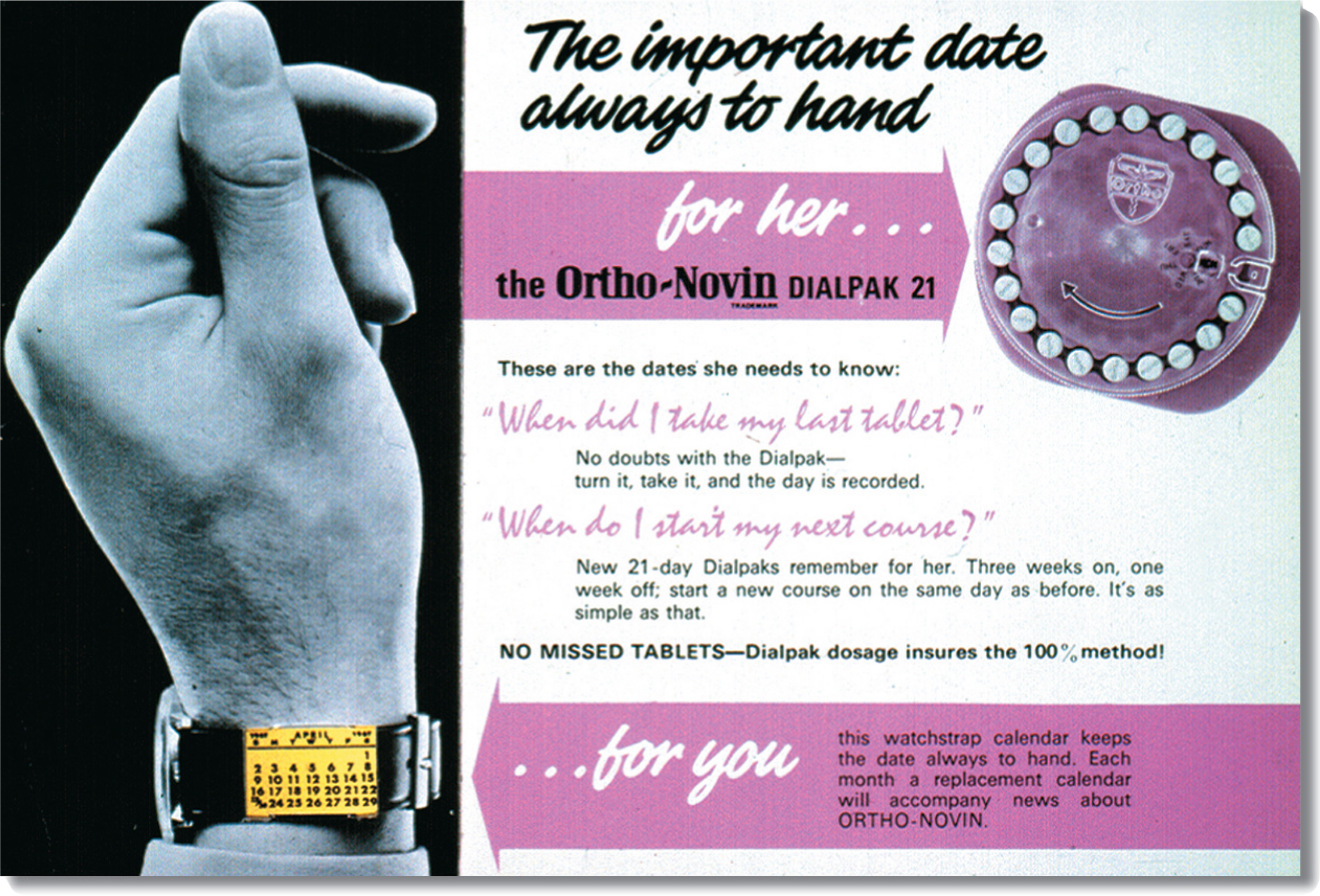

Student protest sometimes blended into a cultural revolution against nearly every conventional standard of behavior. Drawing on the ideas of the Beats of the 1950s (see “Countercurrents” in chapter 27), the “hippies,” as they were called, rejected mainstream values such as consumerism, order, and sexual discipline. Seeking personal rather than political change, they advocated “Do your own thing” and drew attention with their long hair, wildly colorful clothing, and drug use. Across the country, thousands of radicals established communes in cities or on farms, where they renounced private property and shared everything. (See “Visualizing History.”)

Rock and folk music defined both the counterculture and the political left. Music during the 1960s often carried insurgent political and social messages that reflected radical youth culture. “Eve of Destruction,” a top hit of 1965, reminded young men at a time when the voting age was twenty-