Assessing the Great Society

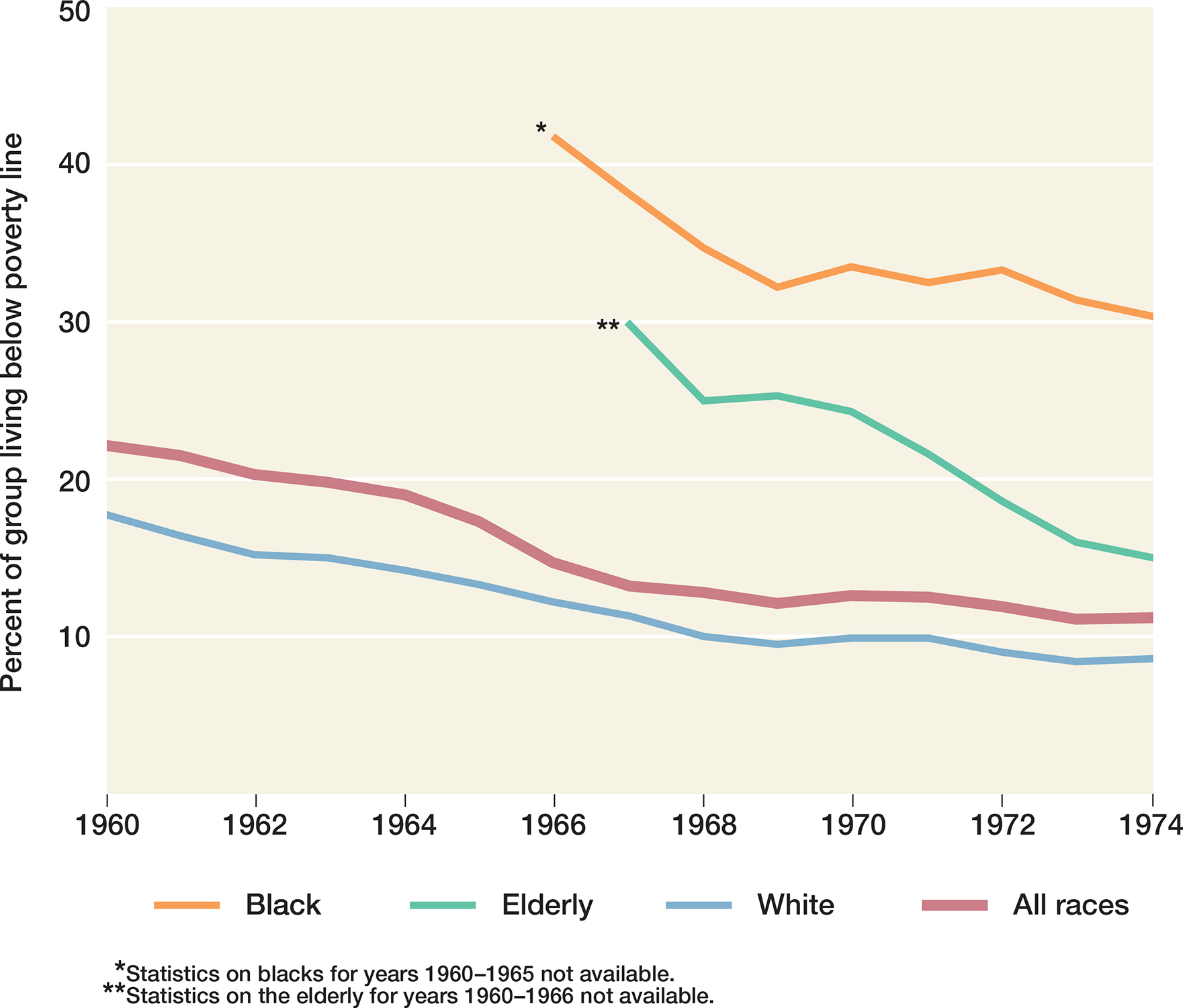

The reduction in poverty in the 1960s was considerable. The number of poor Americans fell from more than 20 percent of the population in 1959 to around 13 percent in 1968. Those who in Johnson’s words “live on the outskirts of hope” saw new opportunities. To Rosemary Bray, what turned her family of longtime welfare recipients into taxpaying workers “was the promise of the civil rights movement and the war on poverty.” A Mexican American who learned to be a sheet metal worker through a jobs program reported, “[My children] will finish high school and maybe go to college. . . .

Certain groups, especially the aged, fared better than others. Many male-

Conservative critics charged that Great Society programs discouraged initiative by giving the poor “handouts.” Liberal critics claimed that focusing on training and education wrongly blamed the poor themselves rather than an economic system that could not provide enough adequately paying jobs. In contrast to the New Deal, the Great Society avoided structural reform of the economy and spurned public works projects as a means of providing jobs for the disadvantaged.

Some critics insisted that ending poverty required raising taxes in order to create jobs, overhaul welfare systems, and rebuild slums. Great Society programs did invest more heavily in the public sector, but the Great Society was funded from economic growth rather than from new taxes on the rich or middle-