The Tumultuous Election of 1968

Disorder and violence also entered the election process. In June, two months after the murder of Martin Luther King Jr. and the riots that followed, antiwar candidate Senator Robert F. Kennedy, campaigning for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination, was killed by a Palestinian Arab refugee because of his support for Israel.

In August, protesters battled the police in Chicago, site of the Democratic Party national convention. Several thousand demonstrators came to the city, some to support peace candidate Senator Eugene McCarthy, others to cause disruption. On August 25, when demonstrators jeered at orders to disperse, police attacked them with tear gas and clubs. Street battles continued for three days, culminating in a police riot on the night of August 28. Taunted by the crowd, the police sprayed Mace and clubbed not only those who had come to provoke violence but also reporters, peaceful demonstrators, and convention delegates.

The bloodshed in Chicago had little effect on the convention’s outcome. Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey believed that the nation was “throwing lives and money down a corrupt rat hole” in Vietnam, but he kept his views to himself and trounced the remaining antiwar candidate, McCarthy, by nearly three to one for the Democratic nomination.

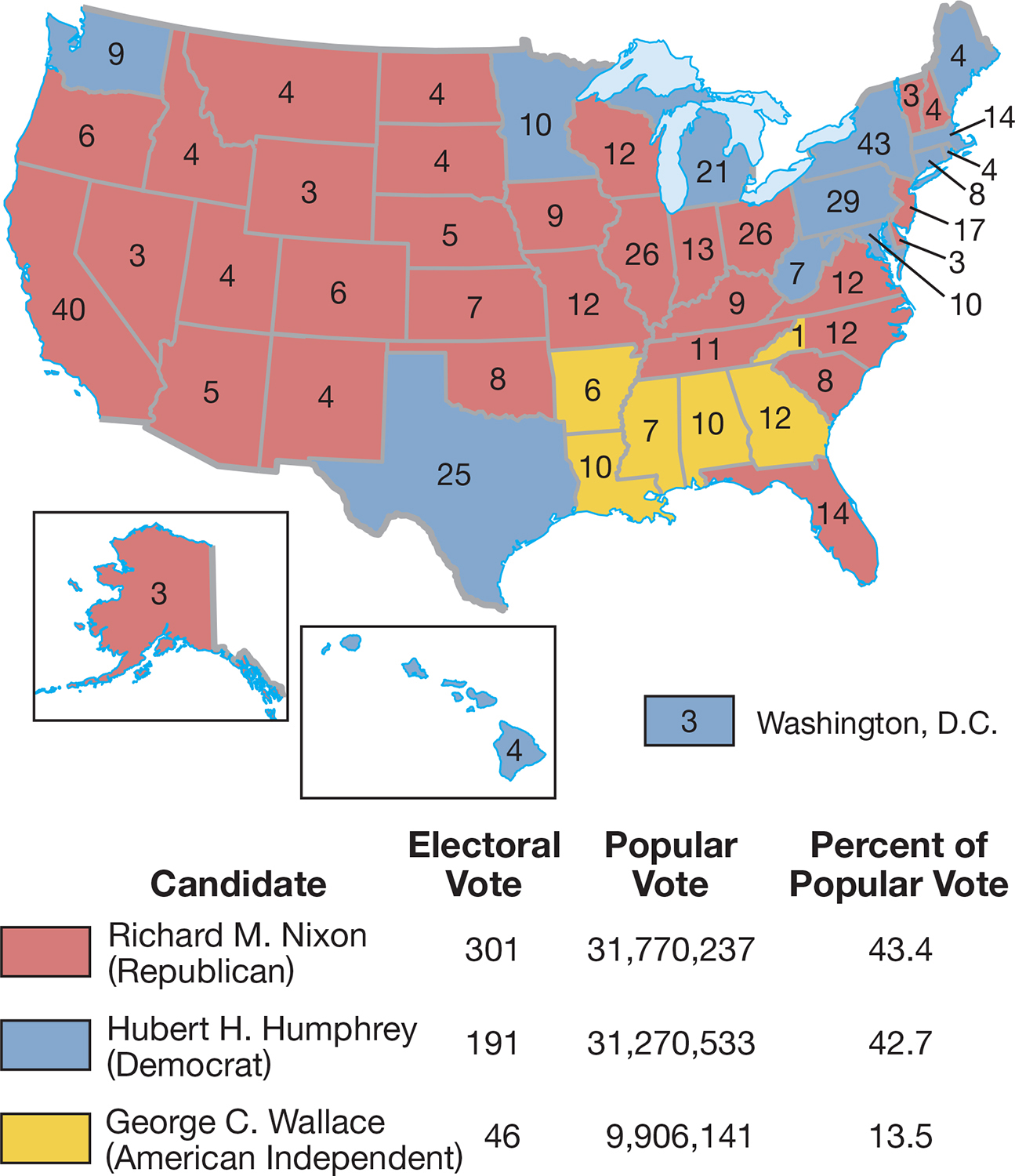

In contrast to the turmoil in Chicago, the Republican convention met peacefully and nominated former vice president Richard Nixon. In a bid for southern support, Nixon chose Maryland governor Spiro T. Agnew for his running mate. A strong third candidate entered the race when the American Independent Party nominated staunch segregationist George C. Wallace. The former Alabama governor appealed to Americans’ dissatisfaction with the reforms and rebellions of the 1960s and their outrage at the assaults on traditional values. Nixon guardedly played on resentments that fueled the Wallace campaign, calling for “law and order” and attacking liberal Supreme Court decisions, busing for school desegregation, and protesters.

The two major party candidates differed little on the central issue of Vietnam. Nixon promised “an honorable end” to the war but did not indicate how to achieve it. Humphrey had reservations about U.S. policy in Vietnam, yet as vice president he was tied to Johnson’s policies. Winning nearly 13 percent of the total popular vote, Wallace produced the strongest third-

The 1968 election revealed deep cracks in the coalition that had maintained Democratic dominance in Washington for the previous thirty years. Johnson’s liberal policies on race shattered a century of Democratic Party rule in the South, which delivered all its electoral votes to Wallace and Nixon. Elsewhere, large numbers of blue-

REVIEW: How did the war in Vietnam polarize the nation?