Moving toward Détente with the Soviet Union and China

Nixon perceived that the “rigid and bipolar world of the 1940s and 1950s” was changing, and America’s European allies were seeking to ease East-

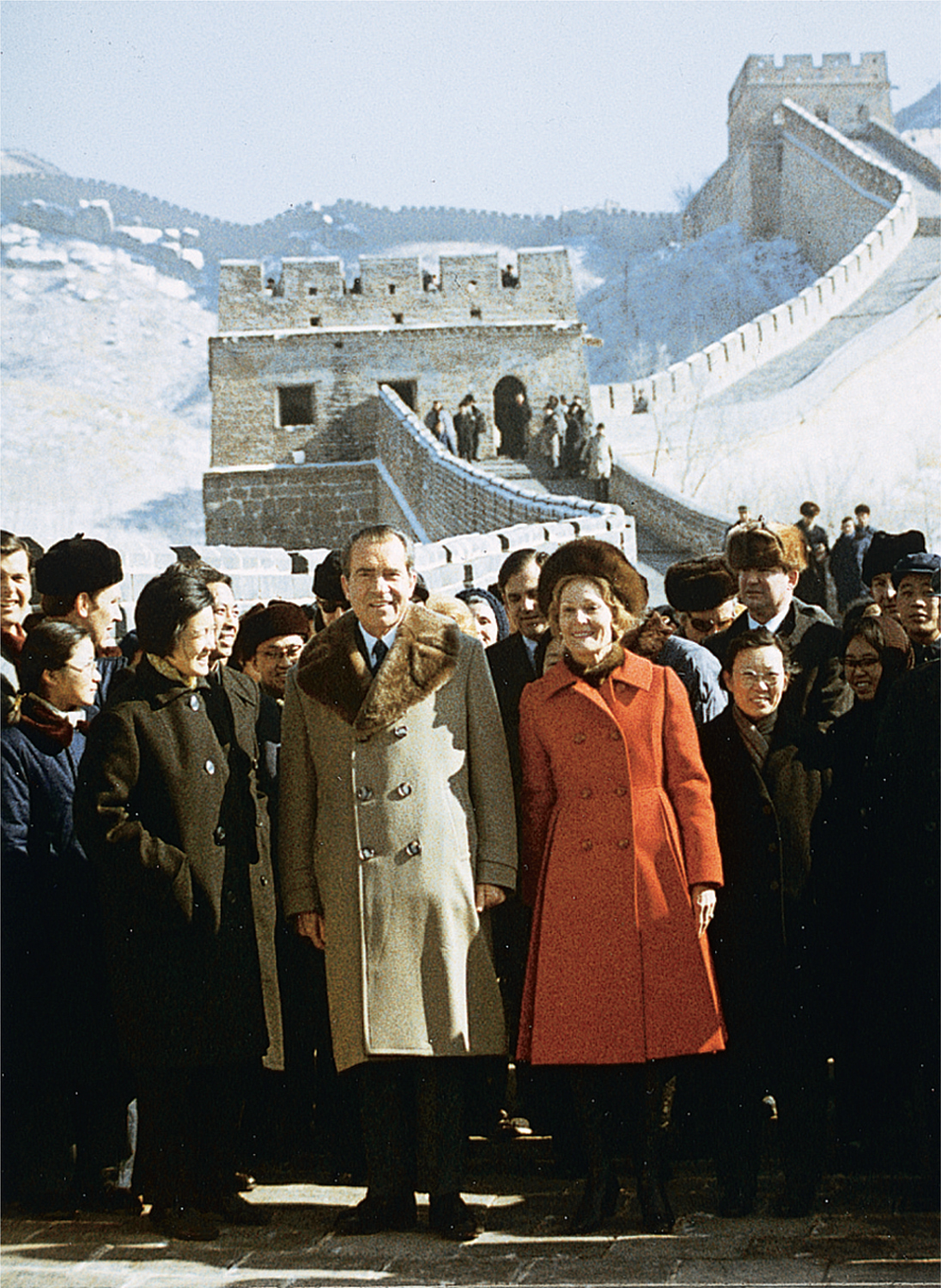

Following two years of secret negotiations, in February 1972 Nixon became the nation’s first president to set foot on Chinese soil, an astonishing move by one who had built his career on anticommunism. Although his visit was largely symbolic, cultural and scientific exchanges followed, and American manufacturers began to find markets in China—

As Nixon and Kissinger had hoped, the warming of U.S.-Chinese relations furthered their strategy of détente, their term for easing conflict with the Soviet Union. Détente did not mean abandoning containment; instead it focused on issues of common concern, such as arms control and trade. Containment now would be achieved not just by military threat but also by ensuring that the Soviets and Chinese had stakes in a stable international order. Nixon’s goal was “a stronger healthy United States, Europe, Soviet Union, China, Japan, each balancing the other.”

Arms control, trade, and stability in Europe were three areas where the United States and the Soviet Union had common interests. In May 1972, Nixon visited Moscow, signing agreements on trade and cooperation in science and space. Most significantly, Soviet and U.S. leaders concluded arms limitation treaties that had grown out of the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) begun in 1969, agreeing to limit antiballistic missiles (ABMs) to two each. Giving up pursuit of a defense against nuclear weapons was a crucial move because it denied both nations an ABM defense so secure against a nuclear attack that they would risk a first strike.

Although détente made little progress after 1974, U.S., Canadian, Soviet, and European leaders signed a historic agreement in 1975 in Helsinki, Finland, that formally recognized the post–