A Growing War in Vietnam

In 1963, Kennedy criticized the idea of “a Pax Americana enforced on the world by American weapons of war,” but he had already increased the flow of those weapons into South Vietnam. Kennedy’s strong anticommunism and attachment to a vigorous foreign policy prepared him to expand the commitment that he had inherited from Eisenhower.

By the time Kennedy took office, more than $1 billion in aid and seven hundred U.S. military advisers had failed to stabilize South Vietnam. Two major obstacles stood in the way. First, the South Vietnamese insurgents—

Second, the South Vietnamese government refused to satisfy insurgents’ demands, but the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) could not defeat them militarily. Ngo Dinh Diem, South Vietnam’s premier from 1954 to 1963, chose self-

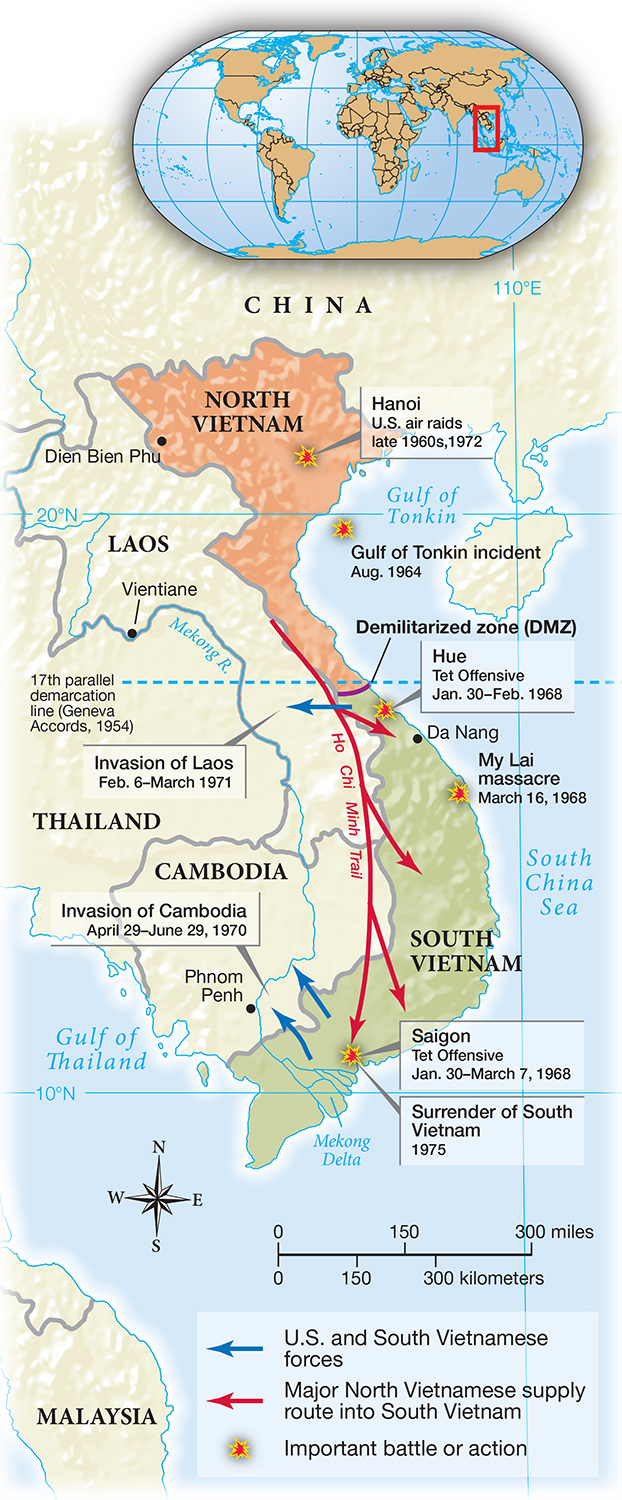

Stability and popular support enabled the Hanoi government in the North to wage war in the South. In 1960, it established the National Liberation Front (NLF), composed of South Vietnamese rebels but directed by the northern army. In addition, Hanoi constructed a network of infiltration routes, called the Ho Chi Minh Trail, in neighboring Laos and Cambodia, through which it sent people and supplies to help liberate the South (Map 29.2). Violence escalated between 1960 and 1963, bringing the Saigon government close to collapse.

In response, Kennedy gradually escalated the U.S. commitment. By spring 1963, military aid had doubled, and 9,000 Americans served in Vietnam as military advisers, occasionally participating in actual combat. The South Vietnamese government promised reform but never made good on its promises.

American officials assumed that technology and sheer power could win in Vietnam. Yet advanced weapons were ill suited to the guerrilla warfare practiced by the enemy, whose surprise attacks were designed to weaken support for the South Vietnamese government. Moreover, U.S. weapons and strategy harmed the very people they were intended to save. Thousands of peasants were uprooted or fell victim to bombs—

With tacit permission from Washington, South Vietnamese military leaders executed a coup against Diem and his brother, who headed the secret police, in November 1963. Kennedy expressed shock at the murders but indicated no change in policy. In a speech to be given on the day he was assassinated, Kennedy referred specifically to Southeast Asia and warned, “We dare not weary of the task.” At his death, 16,700 Americans were stationed in Vietnam, and 100 had died there.

REVIEW: Why did Kennedy believe that engagement in Vietnam was crucial to his foreign policy?