The Ford Presidency and the 1976 Election

Upon taking office, Gerald R. Ford announced, “Our long national nightmare is over.” But he shocked many Americans one month later by granting Nixon a pardon “for all offenses against the United States which he . . .

Congress’s efforts to guard against the types of abuses revealed in the Watergate investigations had only limited effects. The Federal Election Campaign Act of 1974 established public financing of presidential campaigns and imposed some restrictions on contributions to curtail the selling of political favors. Yet politicians found other ways of raising money—

Congressional investigating committees discovered a host of illegal FBI and CIA activities stretching back to the 1950s, including surveillance of American citizens like Martin Luther King Jr., harassment of political dissenters, and plots to assassinate Fidel Castro and other foreign leaders. In response to these revelations, President Ford established new controls on covert operations, and Congress created permanent committees to oversee the intelligence agencies. Yet these measures did little to diminish the public’s cynicism about their government or to curtail massive government surveillance of private communications that accompanied terrorist threats to the United States in the twenty-

The Democrats nominated James Earl “Jimmy” Carter Jr., former governor of Georgia. A graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy, Carter spent seven years as a nuclear engineer in the navy before returning to Plains, Georgia, to run the family peanut farming business. Carter stressed his faith as a “born-

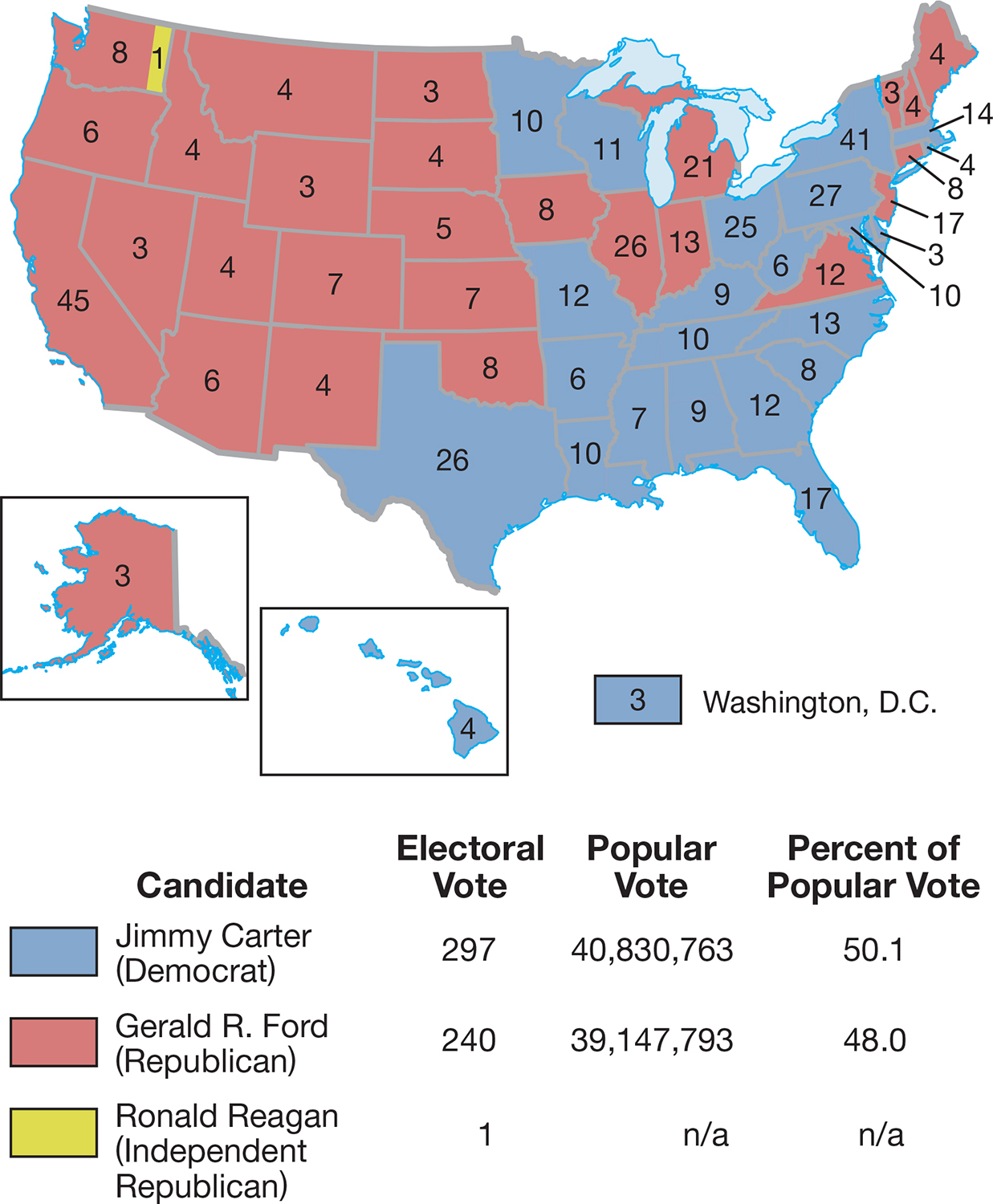

Carter had considerable appeal as a candidate who carried his own bags, lived modestly, and taught a Bible class at his Baptist church. He also benefited from Ford’s failure to solve the country’s economic problems, which helped him win the traditional Democratic coalition of blacks, organized labor, and ethnic groups and even recapture some of the white southerners who had voted for Nixon in 1972. Still, Carter received just 50 percent of the popular vote to Ford’s 48 percent, while Democrats retained substantial margins in Congress (Map 30.1).

REVIEW: How did Nixon’s policies reflect the increasing influence of conservatives on the Republican Party?