Nixon Courts the Right

Highlighting law and order in his 1968 presidential campaign, Nixon appealed to “forgotten Americans, those who did not indulge in violence, those who did not break the law.” He also exploited hostility to black protest and new civil rights policies to woo white southerners and a considerable number of northern voters away from the Democratic Party. As president, he used this “southern strategy” to make further inroads into traditional Democratic strongholds in the 1972 election.

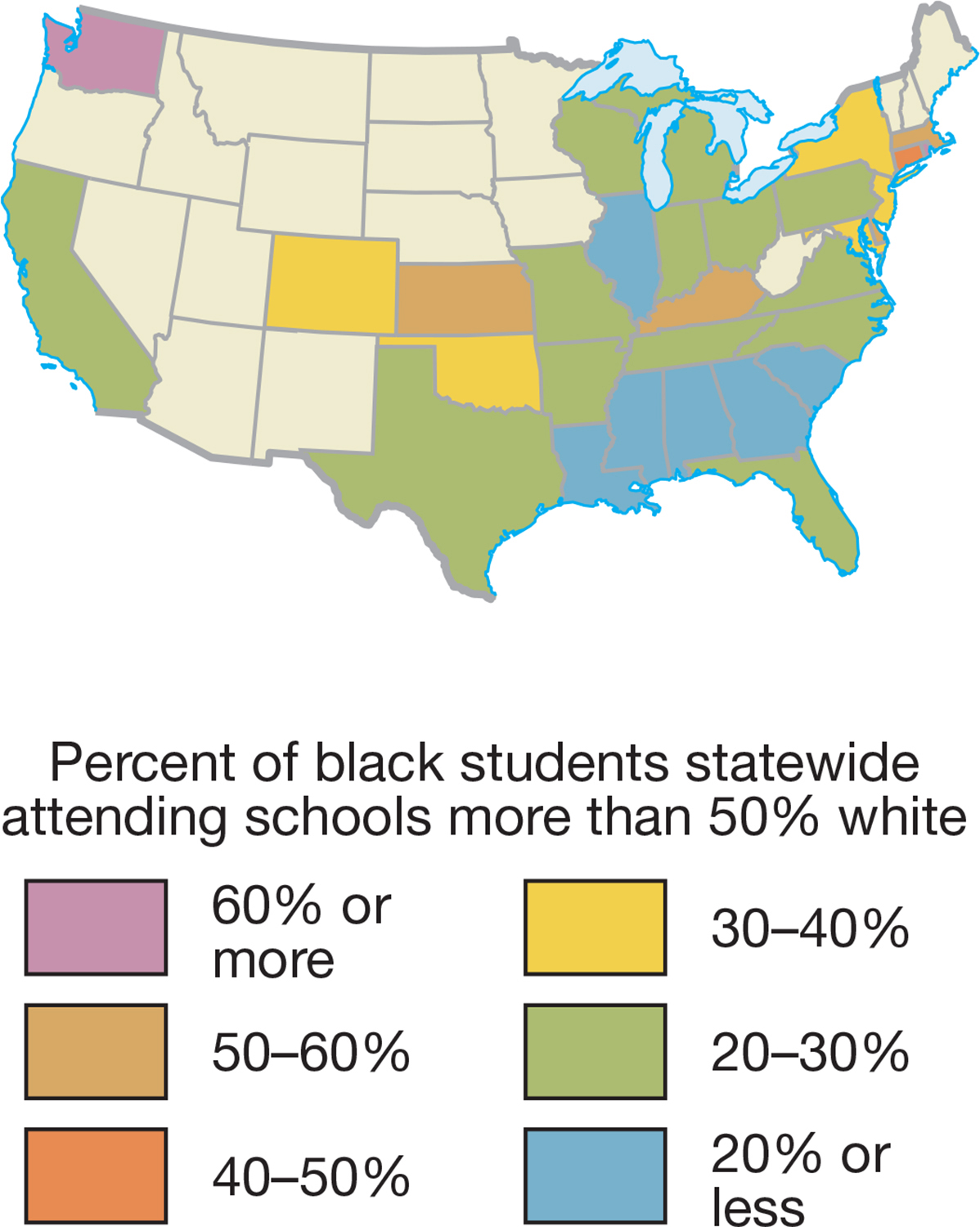

Nixon reluctantly enforced court orders to achieve high degrees of integration in southern schools, but he resisted efforts to deal with segregation outside the South. In northern and western cities, where segregation resulted from discrimination in housing and in the drawing of school district boundaries, half of all African American children attended nearly all-

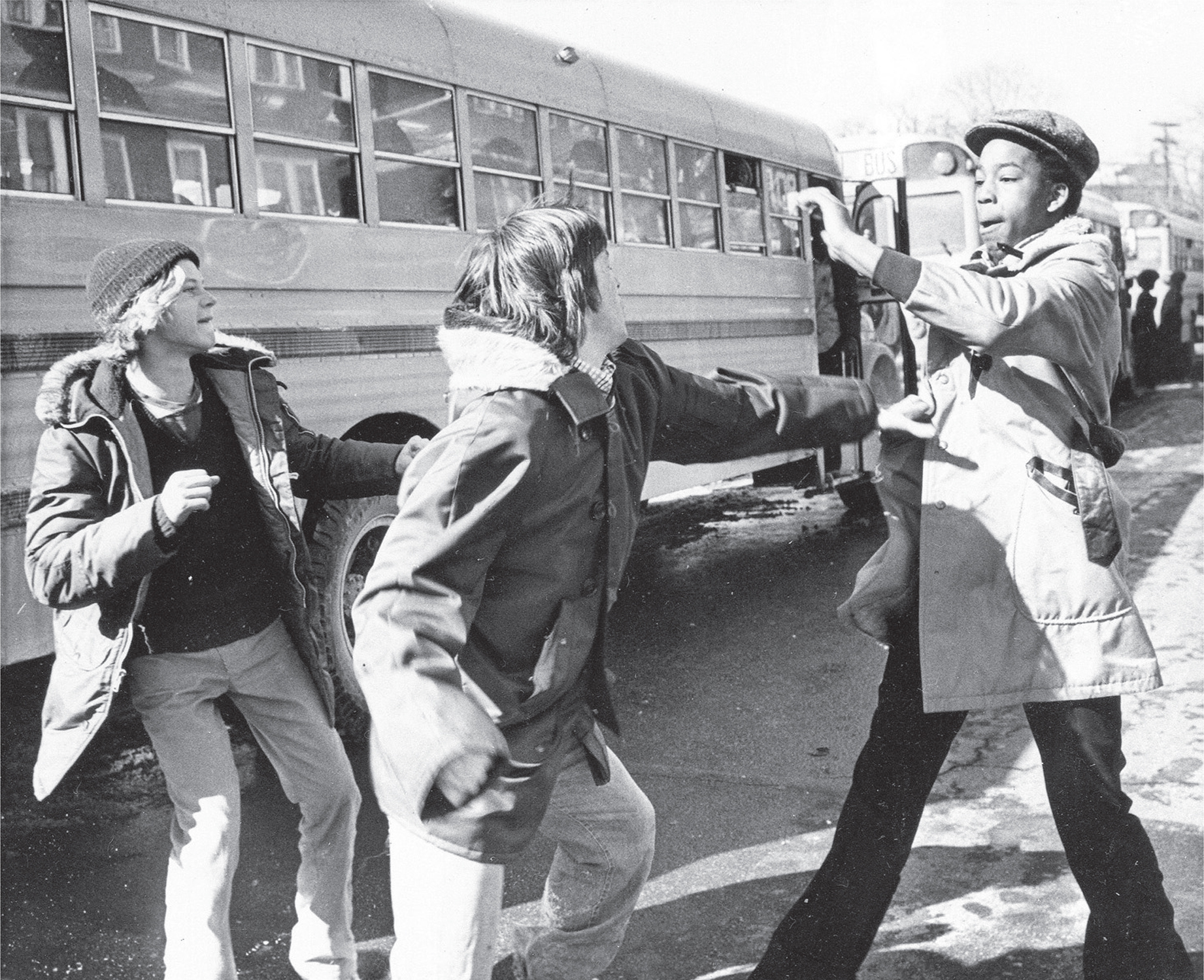

Children had been riding buses to school for decades, but busing for racial integration provoked fury. Violence erupted in Boston in 1974 when a district judge found that school officials had maintained what amounted to a dual system based on race and ordered busing “if necessary to achieve a unitary school system.” The whites most affected by busing came from working-

Whites eventually became more accepting of integration, especially after the creation of schools with specialized programs and other new mechanisms for desegregation offered greater choice. Nonetheless, integration propelled white flight to the suburbs. Nixon failed to persuade Congress to end court-

Nixon’s judicial appointments also reflected the southern strategy. He criticized the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren for being “unprecedentedly politically active . . .

Nixon’s southern strategy and other repercussions of the civil rights revolution of the 1960s ended the Democratic hold on the “solid South.” Beginning in 1964, a number of conservative southern Democrats changed their party affiliation; by 2005, Republicans held the majority of southern seats in Congress and governorships in seven southern states.

In addition to exploiting racial fears, Nixon appealed to anxieties about women’s changing roles and new demands. In 1971, he vetoed a bill providing federal funds for day care centers with a message that combined the old and new conservatism. Parents should purchase child care services “in the private, open market,” he insisted, not rely on government. He appealed to social conservatives by warning about the measure’s “family-