Accommodating the Right

Domestic Terrorism The most devastating product of antigovernment extremism was the explosion of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City in April 1995. The building housed a day care center, and nineteen infants and toddlers were among the 169 killed. Timothy McVeigh, who drove the bomb-rigged truck, was executed in 2001, and his co-conspirator, Terry Nichols, was sentenced to life imprisonment without parole. © Charles Porter IV/ZUMAPRESS.com

The 1994 midterm elections swept away the Democratic majorities in Congress and helped push Clinton to the right. Led by Representative Newt Gingrich of Georgia, Republicans claimed the 1994 election as a mandate for their “contract with America,” a conservative platform to end “government that is too big, too intrusive, and too easy with the public’s money” and to elect “a Congress that respects the values and shares the faith of the American family.”

The most extreme antigovernment sentiment developed far from Washington in the form of grassroots armed militias that stock-piled weapons, celebrated white Christian supremacy, and reflected conservatives’ hostility to such diverse institutions as taxes and the United Nations. The militia movement grew after passage of new gun control legislation and after government agents stormed the headquarters of an armed religious cult in Waco, Texas, in April 1993, killing more than 80. On the second anniversary of that event, militia sympathizers bombed a federal building in Oklahoma City, taking 169 lives in the worst terrorist attack in the nation’s history up to that point.

Clinton bowed to conservative views on gay and lesbian rights, and, following the advice of military leaders, backed away from his promise to lift the ban on gays in the military. Homo-sexual soldiers would be safe from discharge only if they kept their sexual orientations secret. Cathleen Glover, an army specialist in Arabic who lost her position along with thou-sands of other soldiers, lamented, “The army preaches integrity, but asks you to lie to everyone around you.” In addition, in 1996, Clinton signed the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), prohibiting the federal government from recognizing state-licensed marriages between same-sex couples.

Nonetheless, attitudes and practices relating to homosexuality were changing rapidly. By 2006, a majority of the largest companies provided health benefits to same-sex domestic partners and included sexual orientation in their nondiscrimination policies. A majority of states banned discrimination in public employment, and many of those laws extended to private employment, housing, and education. By 2014, gay marriage was legal in seventeen states and the District of Columbia, while thirty-three states banned it. And in 2013, the Supreme Court overturned DOMA as a violation of the Constitution’s equal protection guarantee. Gay spouses were now entitled to equal treatment in such areas as federal insurance benefits, immigration, and tax filing.

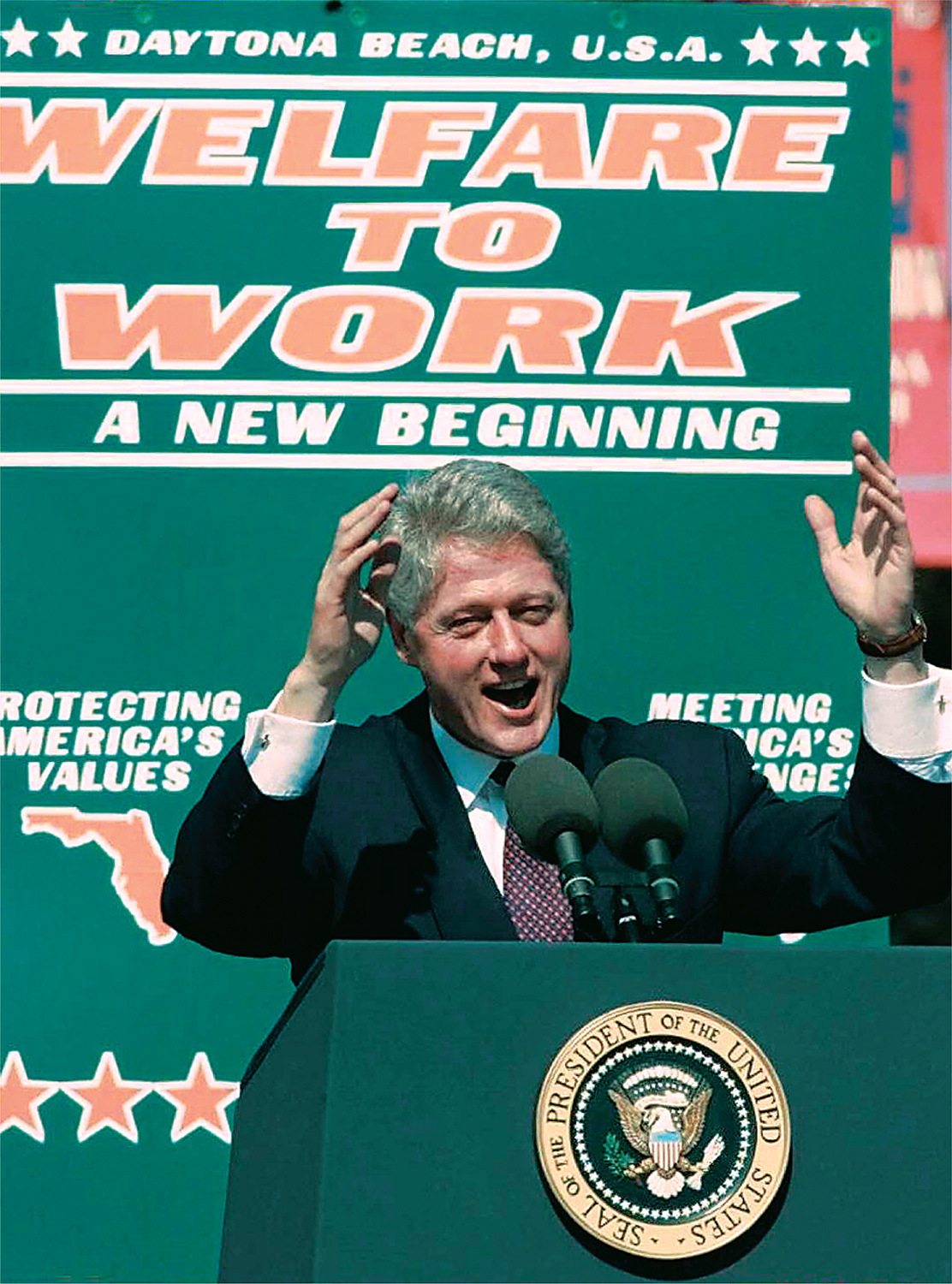

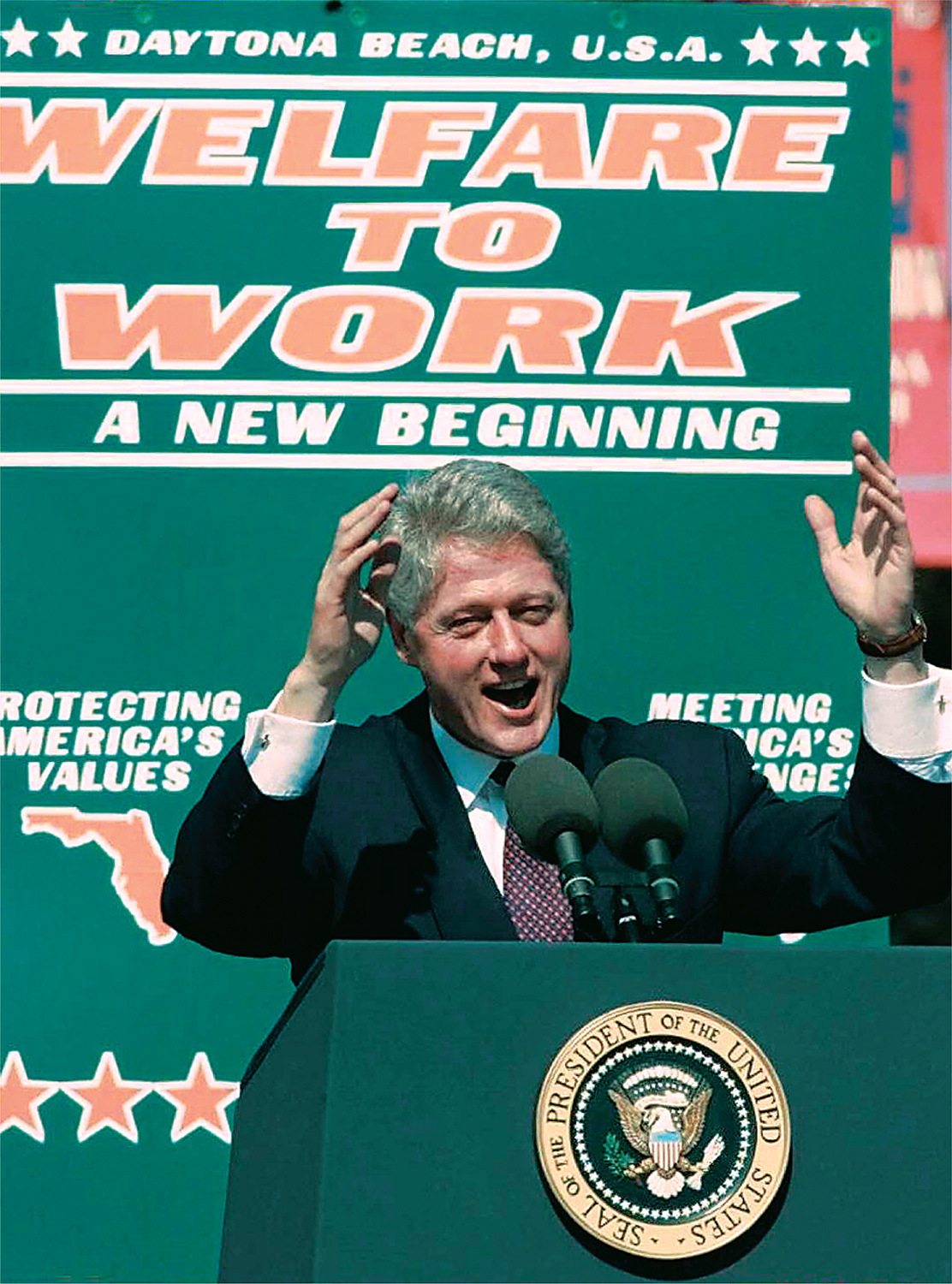

VISUAL ACTIVITY The End of Welfare After signing the bill that sharply curtailed government support for poor mothers and their children, Bill Clinton made it a part of his 1996 campaign for reelection. He highlighted the issue especially when campaigning in more conservative regions, as this photo from a campaign stop in Daytona, Florida, shows. AFP/Getty Images. READING THE IMAGE: What does the poster behind Clinton say about the importance of welfare as an issue in 1996? What “American values” do you think it refers to? CONNECTIONS: What other programs that addressed the issue of poverty did Clinton advance?

Clinton’s efforts to dissociate his party from liberalism were apparent in his handling of the New Deal program Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), popularly called welfare. He responded to changing public sentiment that tended to blame poverty on the poor themselves and on welfare programs that trapped the poor in cycles of dependency, rather than on external circumstances, such as lack of adequate jobs and childcare. Many questioned why they should subsidize poor mothers when so many women worked outside the home. Defenders of AFDC doubted that the economy could provide sufficient jobs at decent wages and pointed to the substantial subsidies the government provided to other groups, such as large farmers, corporations, and homeowners.

After vetoing two welfare bills, Clinton signed a less punitive measure as the 1996 election approached. The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act replaced AFDC with Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, which provided grants to the states to assist the poor. It limited welfare payments to two consecutive years, with a lifetime maximum of five years.

Clinton’s signature on the new law denied Republicans a partisan issue in the 1996 presidential campaign. The Republican Party also moved to the center, nominating Kansan Robert Dole, a World War II hero and former Senate majority leader. Clinton won 49 percent of the votes; 41 percent went to Dole and 9 percent to third-party candidate Ross Perot. Voters sent a Republican majority back to Congress.

In 1999, Clinton and Congress further deregulated the financial industry by repealing key aspects of the Glass-Steagall Act, passed during the New Deal to avoid another Great Depression. The Financial Services Modernization Act ended the separation between banking, securities, and insurance services, allowing financial institutions to engage in all three areas, practices that contributed to the severe financial meltdown of 2008.