Governing during Economic Crisis and Political Polarization

Obama won an election that represented momentous changes in American politics. The Republican nominee, Senator John McCain of Arizona, a Vietnam War hero, chose as his running mate Alaska governor Sarah Palin, the first Republican woman to run for vice president. Even more historic changes occurred in the Democratic Party when, for the first time, an African American and a woman were the top two contenders. (See “Visualizing History.”) In hard-

Born to a white mother and a Kenyan father and raised in Hawai’i and Indonesia, Obama was the first African American to head the Harvard Law Review. He settled in Chicago, served in the Illinois Senate, and won election to the U.S. Senate in 2004. At the age of forty-

Defining “individual responsibility and mutual responsibility” as “the essence of the American promise,” Obama hoped to work across party lines as he pursued reforms in health care, education, the environment, and immigration policy, but he confronted a severe economic crisis. A recession had struck in late 2007, fueled by a breakdown in financial institutions that had accumulated trillions of dollars of bad debt, much of it from risky home mortgages. As the recession spread to other parts of the economy and the world, home mortgage foreclosures skyrocketed, major companies went bankrupt, and unemployment rose to 9.8 percent in late 2010, the highest rate in more than twenty-

The crisis was so severe that Congress passed the Bush administration’s $700 billion Troubled Asset Relief Program in 2008 to inject credit into the economy and shore up banks as well as other businesses. Obama followed with the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, $787 billion worth of spending and tax cuts to stimulate the economy and relieve unemployment. He also arranged a federal bailout of General Motors and Chrysler, saving an estimated one million jobs related to the automobile industry. Finally, to address the conditions that triggered the financial crisis, Congress expanded governmental regulation with the Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act in 2010.

Backed by a Democrat-

Obama’s paramount domestic achievement was passage of health care reform, putting the United States in step with all the other advanced nations, which subsidized some kind of health care for all citizens. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 required that nearly everyone carry health insurance, and to that end, it provided subsidies and compelled larger businesses to offer coverage to employees. The law also imposed new regulations on insurance companies to protect health care consumers and contained provisions to limit medical costs. Although liberals failed to get a public option to allow government-

“Obamacare” (a derisive label that was later embraced by its supporters), along with the government bailouts of big corporations, helped fuel a grassroots movement of mostly white, middle-

The Tea Party movement helped Republicans issue a sharp rebuke to Obama in the 2010 midterm elections, turning over the House to the Republicans and cutting into the Democratic majority in the Senate. Although the stock market had rebounded, nearly 10 percent of American workers remained unemployed, and the federal deficit that Obama had inherited from the Bush administration soared to $1.4 trillion.

The intensely polarized political environment posed a roadblock to reducing unemployment and lowering the federal debt. It also thwarted Obama’s efforts to reform environmental and immigration policy. With Republicans in Congress blocking him at every turn, Obama used his executive authority to stiffen requirements on motor vehicle emissions, encourage alternative energy, and protect from deportation undocumented immigrants brought to the United States as children.

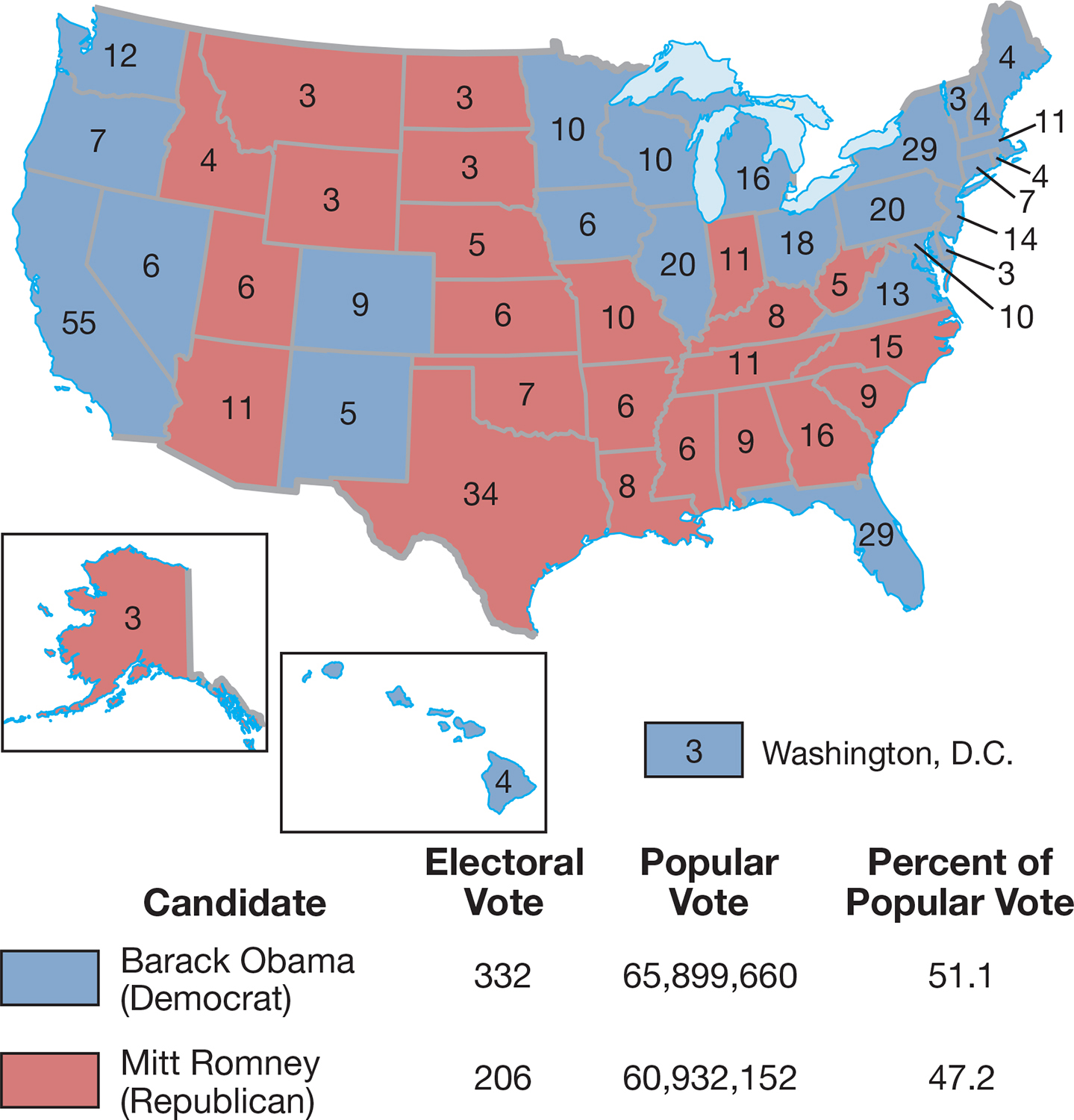

Obama carried the burden of a nearly 8 percent unemployment rate into the 2012 election, where he faced Republican Mitt Romney. With the electorate deeply divided over the role of the federal government, Obama won easily in the electoral college, with 332 votes to Romney’s 206, and he captured 51 percent of the popular vote to Romney’s 47 percent (Map 31.4). The Democrats made small gains in Congress, but Republicans still controlled the House, and, within that majority, Tea Party allies determined to block any legislation that did not cut federal spending.

This stalemate, much more severe than the one during the first Bush administration, prevented the government from getting employment back to prerecession levels and from dealing with a staggering (though shrinking) national deficit and debt. Only the wealthiest 5 percent of Americans had completely recovered from the recession. The richest Americans continued to increase their share of national income, and, in 2013, the United States had the greatest degree of income inequality since the 1920s.