Carolina: A West Indian Frontier

The early settlers of what became South Carolina were immigrants from Barbados. In 1663, a Barbadian planter named John Colleton and a group of seven other men obtained a charter from England’s King Charles II to establish a colony north of the Spanish territories in Florida. The men, known as “proprietors,” hoped to siphon settlers from Barbados and other colonies and encourage them to develop a profitable export crop comparable to West Indian sugar and Chesapeake tobacco. The proprietors enlisted the English philosopher John Locke to help draft the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina, which provided for religious liberty and political rights for small property holders while envisioning a landed aristocracy supported by bound laborers and slaves. Following the Chesapeake example, the proprietors also offered headrights of up to 150 acres of land for each settler, a provision that eventually undermined the Constitutions’ goal of a titled aristocracy. In 1670, the proprietors established the colony’s first permanent English settlement, Charles Towne, later spelled Charleston (see Map 3.2).

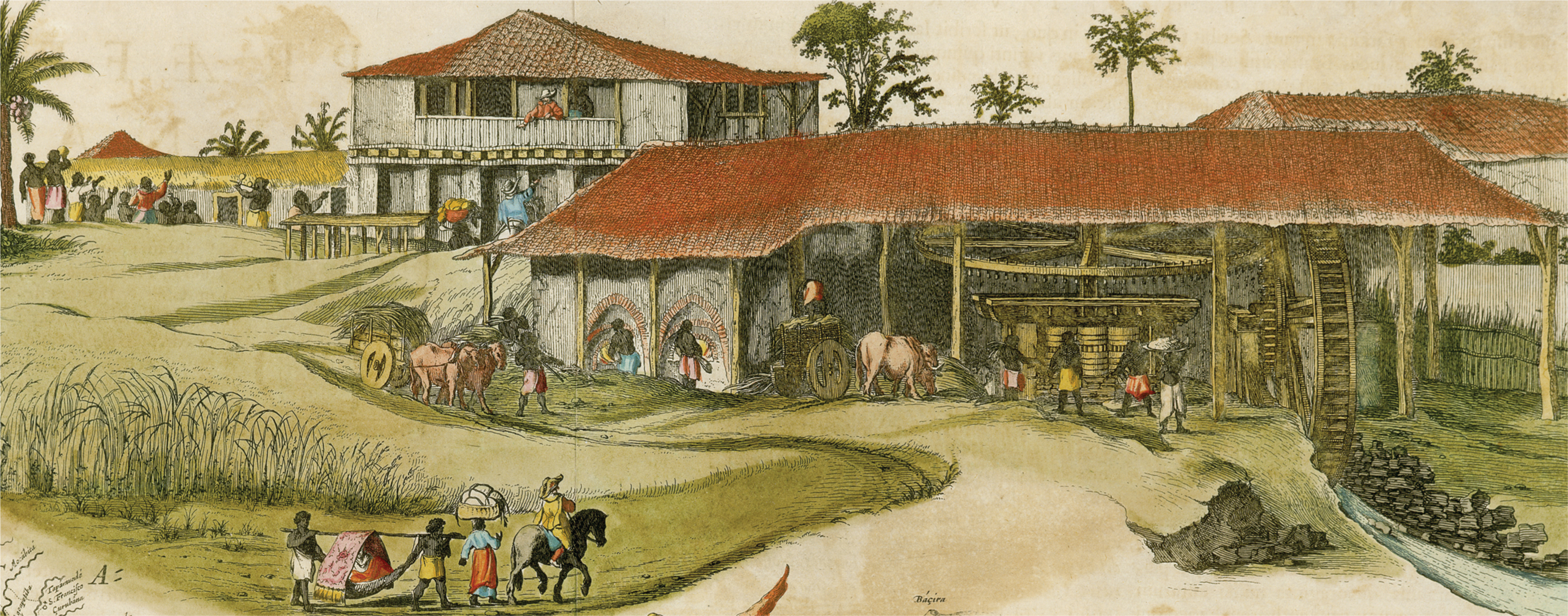

As the proprietors had planned, most of the early settlers were from Barbados, and they brought their slaves with them. More than a fourth of the early settlers were slaves, and by 1700 slaves made up about half the Carolina population. The new colony’s close association with Barbados caused English officials to refer routinely to “Carolina in ye West Indies.”

The Carolinians experimented unsuccessfully to match their semitropical climate with profitable export crops of tobacco, cotton, indigo, and olives. In the mid-