Religious Controversies and Economic Changes

A revolutionary transformation in the fortunes of Puritans in England had profound consequences in New England. Disputes between King Charles I and Parliament, which was dominated by Puritans, escalated in 1642 to civil war in England, a conflict known as the Puritan Revolution. Parliamentary forces led by the staunch Puritan Oliver Cromwell were victorious, executing Charles I in 1649 and proclaiming England a Puritan republic. From 1649 to 1660, England’s rulers were not monarchs who suppressed Puritanism but believers who championed it.

When the Puritan Revolution began, the stream of immigrants to New England dwindled to a trickle, creating hard times for the colonists. They could no longer consider themselves a city on a hill setting a godly example for humankind. Puritans in England, not New England, were reforming English society. Furthermore, when immigrant ships became rare, the colonists faced sky-

New England’s rocky soil and short growing season ruled out cultivating the southern colonies’ crops of tobacco and rice that found ready markets in Atlantic ports. Exports that New Englanders could not get from the soil they took instead from the forest and the sea. By the 1640s, furbearing animals had become scarce unless traders ventured far beyond the frontiers of English settlement. Trees from the seemingly limitless forests of New England proved a longer-

The most important New England export was fish. Dried, salted codfish from the rich North Atlantic fishing grounds found markets in southern Europe and the West Indies. The fish trade also stimulated colonial shipbuilding and trained generations of fishermen, sailors, and merchants. But the lives of most New England colonists revolved around their farms, churches, and families.

Although immigration came to a standstill in the 1640s, the colonial population continued to boom, doubling every twenty years. In New England, almost everyone married, and women often had eight or nine children. Long, cold winters minimized the presence of warm-

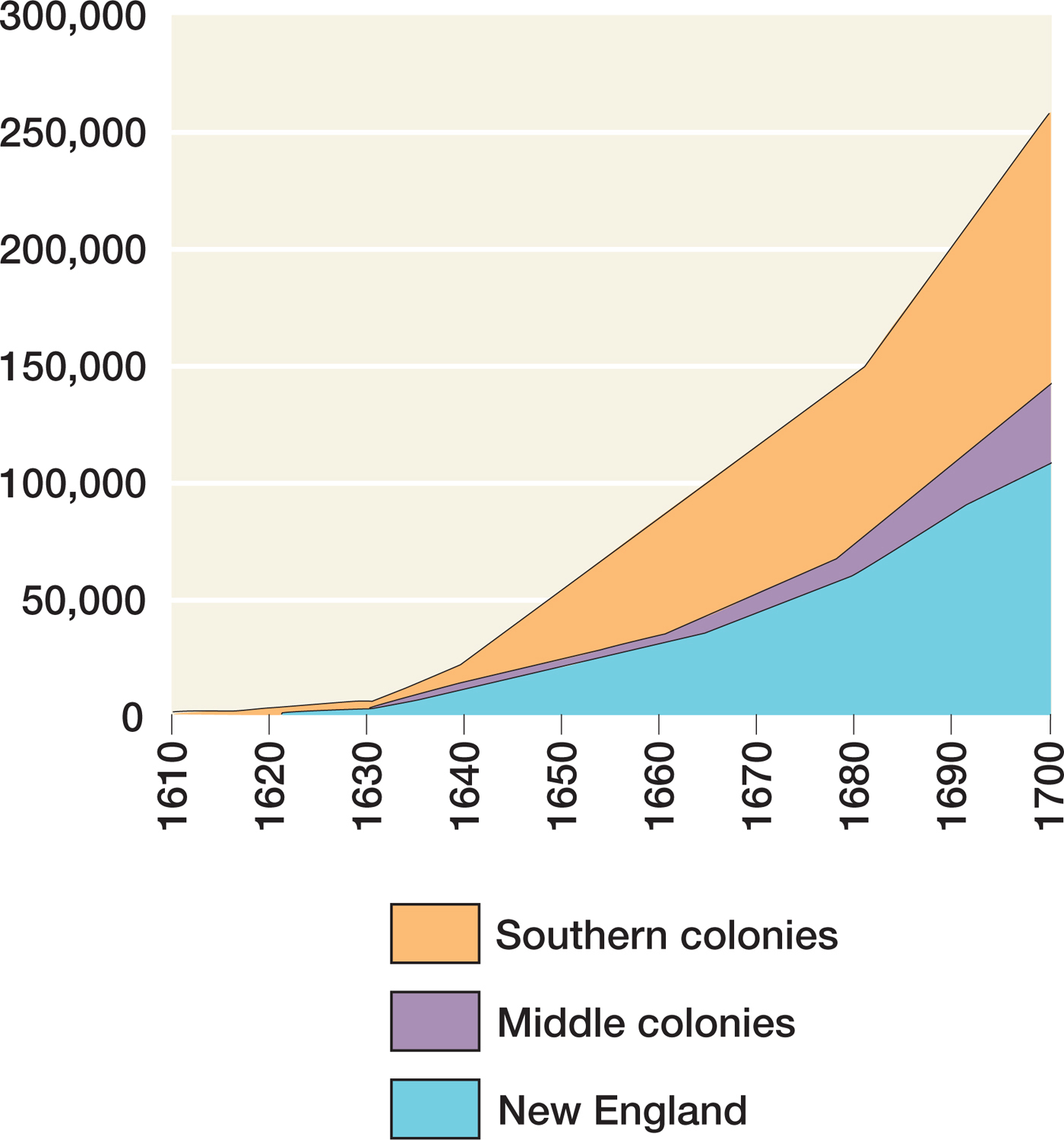

During the second half of the seventeenth century, under the pressures of steady population growth (Figure 4.1) and integration into the Atlantic economy, the red-

How is it that

I find In stead of holiness Carnality;

In stead of heavenly frames an Earthly mind,

For burning zeal luke-

For flaming love, key-

Whence cometh it, that Pride, and Luxurie

Debate, Deceit, Contention and Strife,

False-

. . . amongst them are so rife,

. . . that an honest man can hardly

Trust his Brother?

Most alarming to Puritan leaders, many of the children of the visible saints of Winthrop’s generation failed to experience conversion and attain full church membership. Puritans tended to assume that sainthood was inherited—

Puritan churches debated what to do. To allow anyone, even the child of a saint, to become a church member without conversion was an unthinkable retreat from fundamental Puritan doctrine. In 1662, a synod of Massachusetts ministers reached a compromise known as the Halfway Covenant. Unconverted children of saints would be permitted to become “halfway” church members. Like regular church members, they could baptize their infants. But unlike full church members, they could not participate in communion or have the voting privileges of church membership. The Halfway Covenant generated a controversy that sputtered through Puritan churches for the remainder of the century. With the Halfway Covenant, Puritan churches came to terms with the lukewarm piety that had replaced the founders’ burning zeal.

Nonetheless, New England communities continued to enforce piety with holy rigor. Beginning in 1656, small bands of Quakers—members of the Society of Friends, as they called themselves—

New England communities treated Quakers with ruthless severity. Some Quakers were branded on the face “with a red-

New Englanders’ partial success in realizing the promise of a godly society ultimately undermined the intense appeal of Puritanism. In the pious Puritan communities of New England, leaders tried to eliminate sin. In the process, they diminished the sense of utter human depravity that was the wellspring of Puritanism. By 1700, New Englanders did not doubt that human beings sinned, but they were more concerned with the sins of others than with their own.

Witch trials held in Salem, Massachusetts, signaled the erosion of religious confidence and assurance. From the beginning of English settlement in the New World, more than 95 percent of all legal accusations of witchcraft occurred in New England, a hint of the Puritans’ preoccupation with sin and evil. The most notorious witchcraft trials took place in Salem in 1692, when witnesses accused more than one hundred people of witchcraft, a capital crime. (See “Documenting the American Promise.”) Bewitched young girls shrieked in pain, their limbs twisted into strange contortions, as they pointed out the witches who tortured them. According to the trial court record, the bewitched girls declared that “the shape of [one accused witch] did oftentimes very grievously pinch them, choke them, bite them, and afflict them; urging them to write their names in a book”—the devil’s book. Most of the accused witches were older women, and virtually all of them were well known to their accusers. The Salem court hanged nineteen accused witches and pressed one to death, signaling enduring belief in the supernatural origins of evil and gnawing doubt about the strength of Puritan New Englanders’ faith. Why else, after all, had so many New Englanders succumbed to what their accusers and the judges believed were the temptations of Satan?

REVIEW Why did Massachusetts Puritans adopt the Halfway Covenant?