The Coercive Acts

Lord North’s response was swift and stern: He persuaded Parliament to issue the Coercive Acts, four laws meant to punish Massachusetts for destroying the tea. In America, those laws, along with a fifth one, the Quebec Act, were soon known as the Intolerable Acts. The first act, the Boston Port Act, closed Boston harbor to all shipping as of June 1, 1774, until the destroyed tea was paid for. Britain’s objective was to halt the commercial life of the city. The second act, called the Massachusetts Government Act, greatly altered the colony’s charter, underscoring Parliament’s claim to supremacy over Massachusetts. The royal governor’s powers were augmented, and the governor’s council became an appointive, rather than elective, body. Further, the governor could now appoint all judges, sheriffs, and officers of the court. No town meeting beyond the annual spring election of town selectmen could be held without the governor’s approval, and every agenda item required prior approval. Every Massachusetts town was affected.

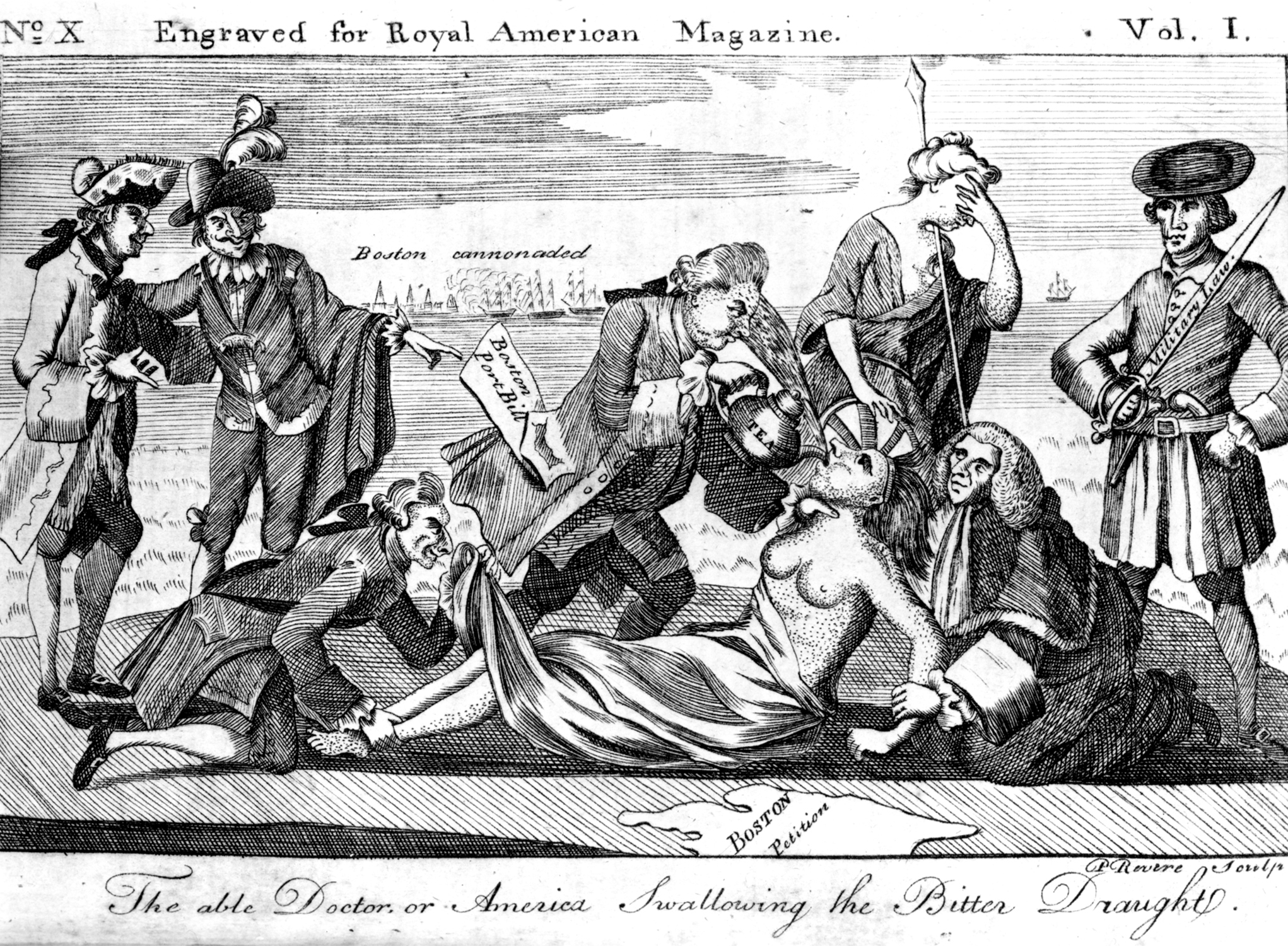

VISUAL ACTIVITY The Able Doctor, or America Swallowing the Bitter Draught, 1774, Engraved by Paul Revere Revere’s cartoon, a response to the Boston Port Act, shows Lord North forcing tea down the throat of America, depicted as an Indian maiden. The older woman is Britannia (known by her shield), who averts her eyes from the attack. Two British lords hold America down, while two other men to the left, representing France and Spain, look on with amusement and pleasure. Private Collection/The Bridgeman Art Library. READING THE IMAGE: How does this cartoon rely on widely shared stereotypes of gender and sexual danger to express power relations in the masculine world of politics? What is gained by representing the country of Britain as a woman, in contrast to the male political figures? CONNECTIONS: According to the Americans, in what sense was Britain forcing them to purchase and drink tea in 1773? Was that sense of coercion still in play in 1774, at the time of this cartoon?

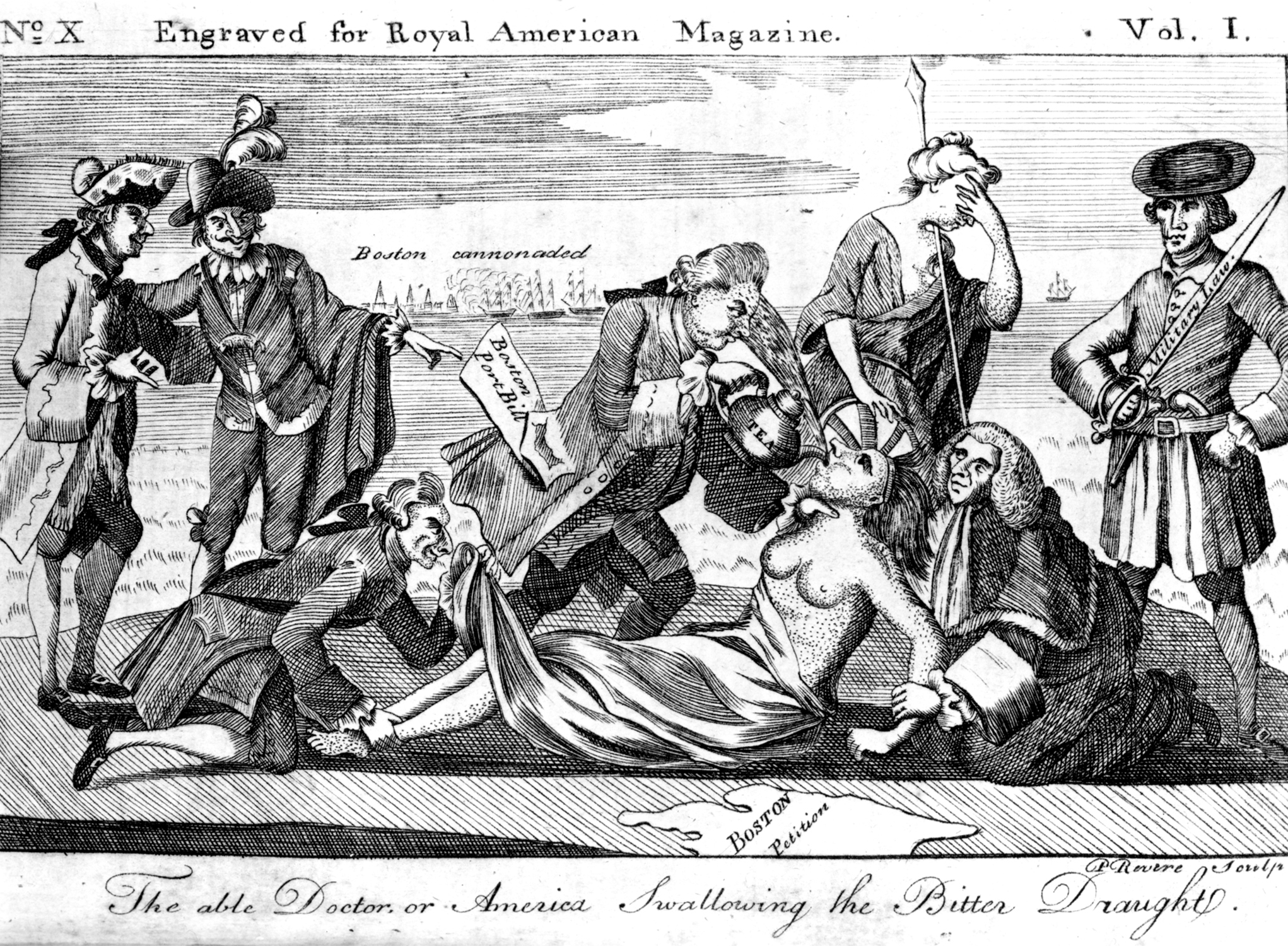

Hutchinson the Traitor Faces Death This hideous engraving enlivened the cover of a Boston almanac published during the high drama over tea. The devil taunts Thomas Hutchinson while a skeleton representing death spears him. On page 2, readers of this anti-Hutchinson diatribe were invited to think about “the Horrors that Man must endure, who owes his Greatness to his Country’s Ruin.” The Granger Collection, New York.

The third Coercive Act, the Impartial Administration of Justice Act, stipulated that any royal official accused of a capital crime—for example, Captain Preston and his soldiers at the Boston Massacre—would be tried in a court in Britain. It did not matter that Preston had received a fair trial in Boston. What this act ominously suggested was that down the road, more Captain Prestons and soldiers might be firing into unruly crowds. The fourth act amended the 1765 Quartering Act and permitted military commanders to lodge soldiers wherever necessary, even in private households. In a related move, Lord North appointed General Thomas Gage, the commander of the Royal Army in New York, to be governor of Massachusetts. Thomas Hutchinson was out, relieved at long last of his duties. Military rule, including soldiers, returned once more to Boston.

The fifth act, concerning Quebec, now part of the British Empire, was unrelated to the four Coercive Acts, but it magnified American fears. It confirmed the continuation of French civil law as well as Catholicism for Quebec—an affront to Protestant New Englanders who had recently been denied their own representative government. It also awarded Quebec land (and the lucrative fur trade) in the Ohio Valley, an area also claimed by Virginia, Pennsylvania, and a number of Indian tribes.

The five Intolerable Acts spread alarm in all the colonies (see “Documenting the American Promise”). If Britain could squelch Massachusetts—change its charter, suspend local government, inaugurate military rule, and on top of that give Ohio to Catholic Quebec—what liberties were secure? Fearful royal governors in a half dozen colonies dismissed the sitting assemblies, adding to the sense of urgency. A few of the assemblies defiantly continued to meet in new locations. Via the committees of correspondence, colonial leaders arranged to convene in Philadelphia in September 1774 to respond to the crisis.