The Loyalists

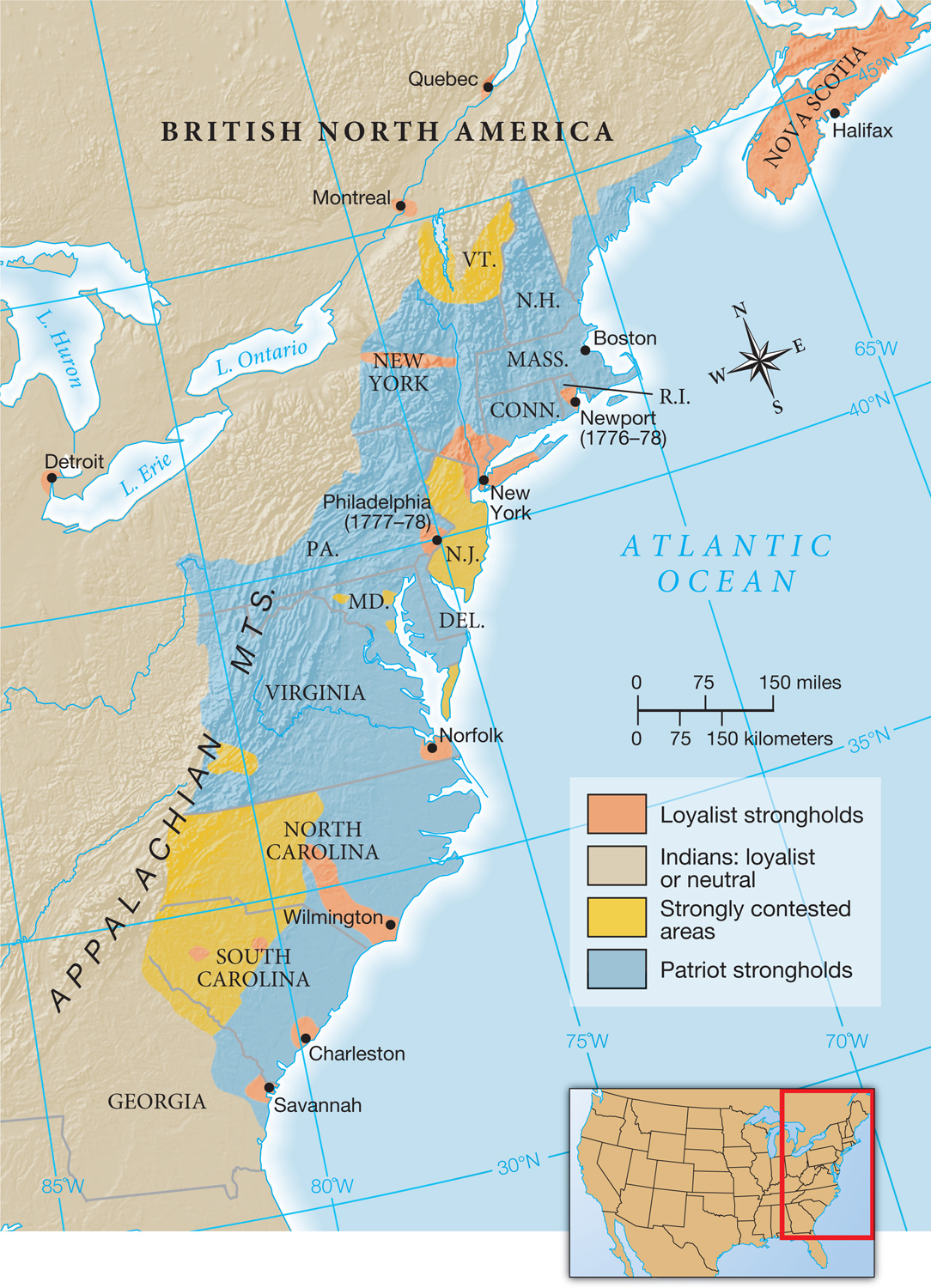

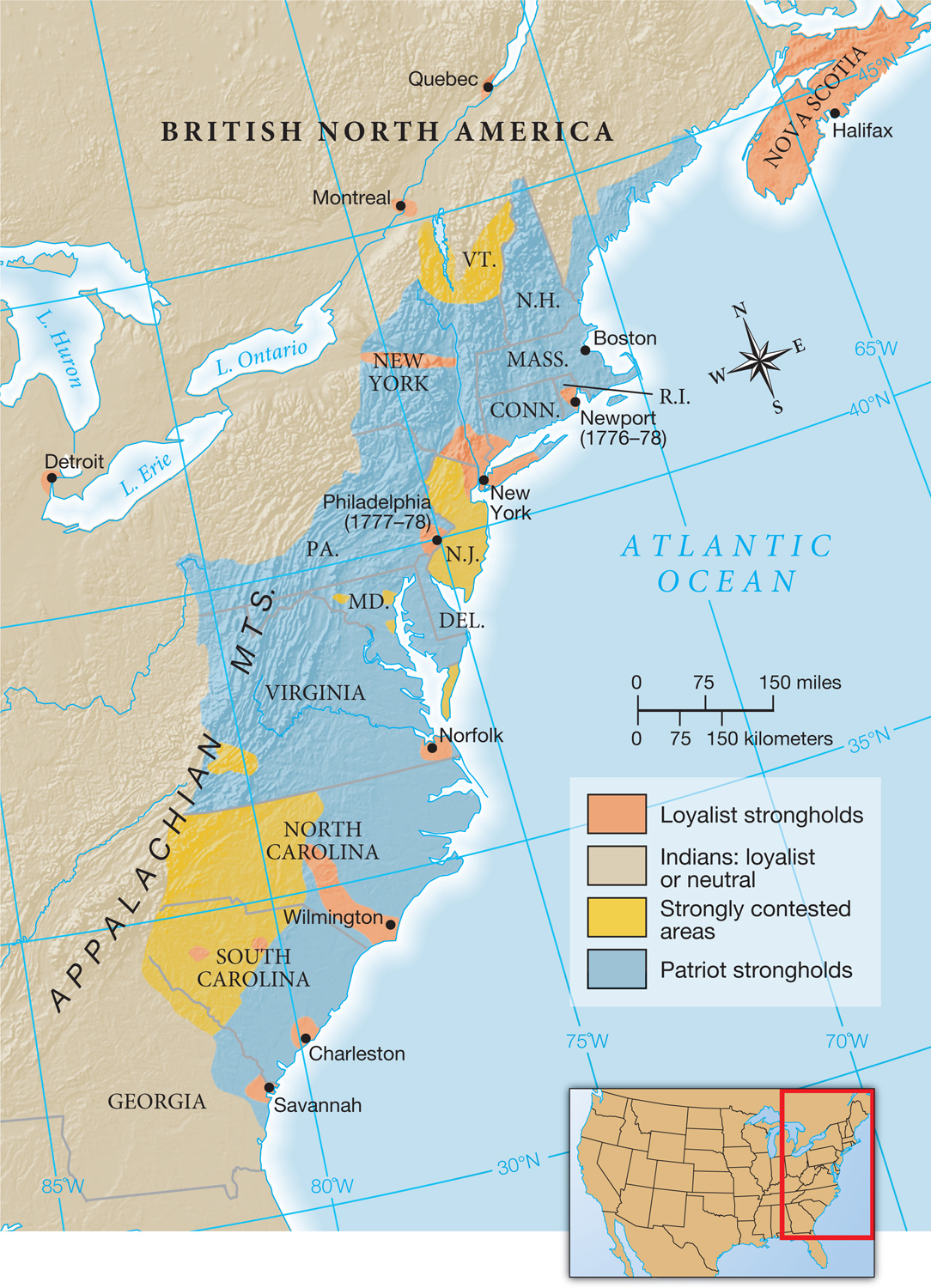

MAP ACTIVITY Map 7.2 Loyalist Strength and Rebel Support The exact number of loyalists can never be known. No one could have made an accurate count at the time, and political allegiance often shifted with the wind. This map shows the regions of loyalist strength on which the British relied—most significantly, the lower Hudson valley and the Carolina Piedmont. READING THE MAP: Which forces were stronger, those loyal to Britain or those rebelling? (Consider the size of their respective areas, centers of population, and vital port locations.) What areas were contested? If the contested areas ultimately had sided with the British, how would the balance of power have changed? CONNECTIONS: Who was more likely to be a loyalist and why? How many loyalists left the United States? Where did they go?

Around one-fifth of the American population remained loyal to the crown in 1776, and another two-fifths tried to stay neutral, providing a strong base for the British. In general, loyalists believed that social stability depended on a government anchored by monarchy and aristocracy. They feared that democratic tyranny was emergent among the self-styled patriots who appeared to be unscrupulous, violent men grabbing power for themselves.

Pockets of loyalism existed everywhere (Map 7.2). The most visible loyalists (called Tories by their enemies) were royal officials, not only governors but also local judges and customs officers. Wealthy merchants gravitated toward loyalism to maintain the trade protections of navigation acts and the British navy. Conservative urban lawyers admired the stability of British law and order. Some colonists chose loyalism simply to oppose traditional adversaries, for example many backcountry Carolina farmers who resented the power of the pro-revolution gentry. Southern slaves had their own resentments against the white slave-owning class and looked to Britain in hope of freedom. Even New England towns at the heart of the turmoil, such as Concord, Massachusetts, had a small and increasingly silenced core of loyalists. On occasion, husbands and wives, fathers and sons disagreed completely on the war. (See “Documenting the American Promise.”)

Many Indian tribes chose neutrality at the war’s start, seeing the conflict as a civil war between the English and Americans. Eventually, however, they were drawn in, most taking the British side. The powerful Iroquois Confederacy divided: The Mohawk, Cayuga, Seneca, and Onondaga peoples lined up with the British; the Oneida and Tuscarora tribes aided Americans. One young Mohawk leader, Thayendanegea (known also by his English name, Joseph Brant), traveled to England in 1775 to complain to King George about land-hungry New York settlers. “It is very hard when we have let the King’s subjects have so much of our lands for so little value,” he wrote, “they should want to cheat us in this manner of the small spots we have left for our women and children to live on.” Brant pledged Indian support for the king in exchange for protection from encroaching settlers. In the Ohio Country, parts of the Shawnee and Delaware tribes started out pro-American but shifted to the British side by 1779 in the face of repeated betrayals by American settlers and soldiers.

Loyalists were most vocal between 1774 and 1776, when the possibility of a full-scale rebellion against Britain was still uncertain. They challenged the emerging patriot side in pamphlets and newspapers. In 1776 in New York City, 547 loyalists signed and circulated a broadside titled “A Declaration of Dependence” in rebuttal to the congress’s July 4 declaration, denouncing the “most unnatural, unprovoked Rebellion that ever disgraced the annals of Time.”

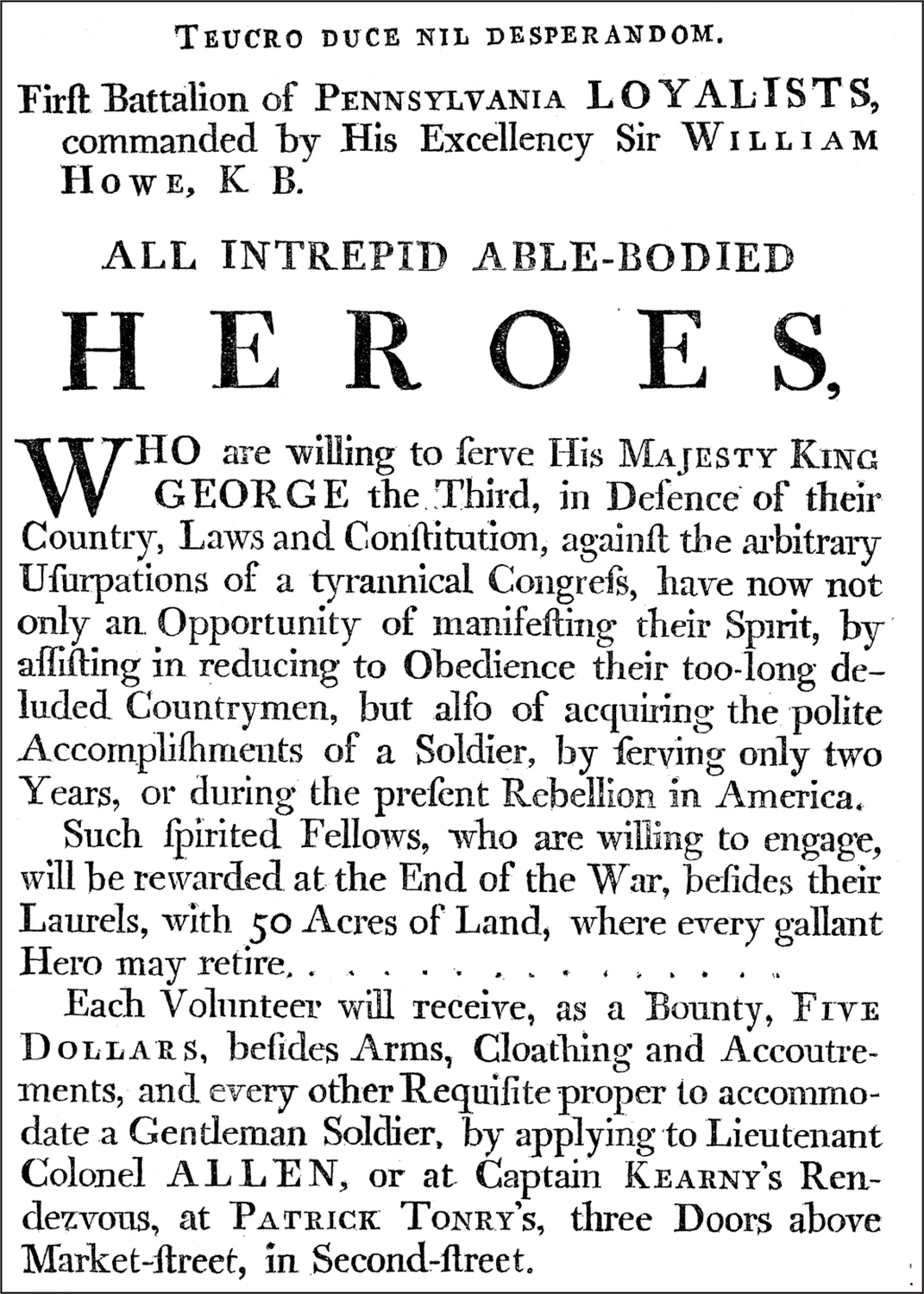

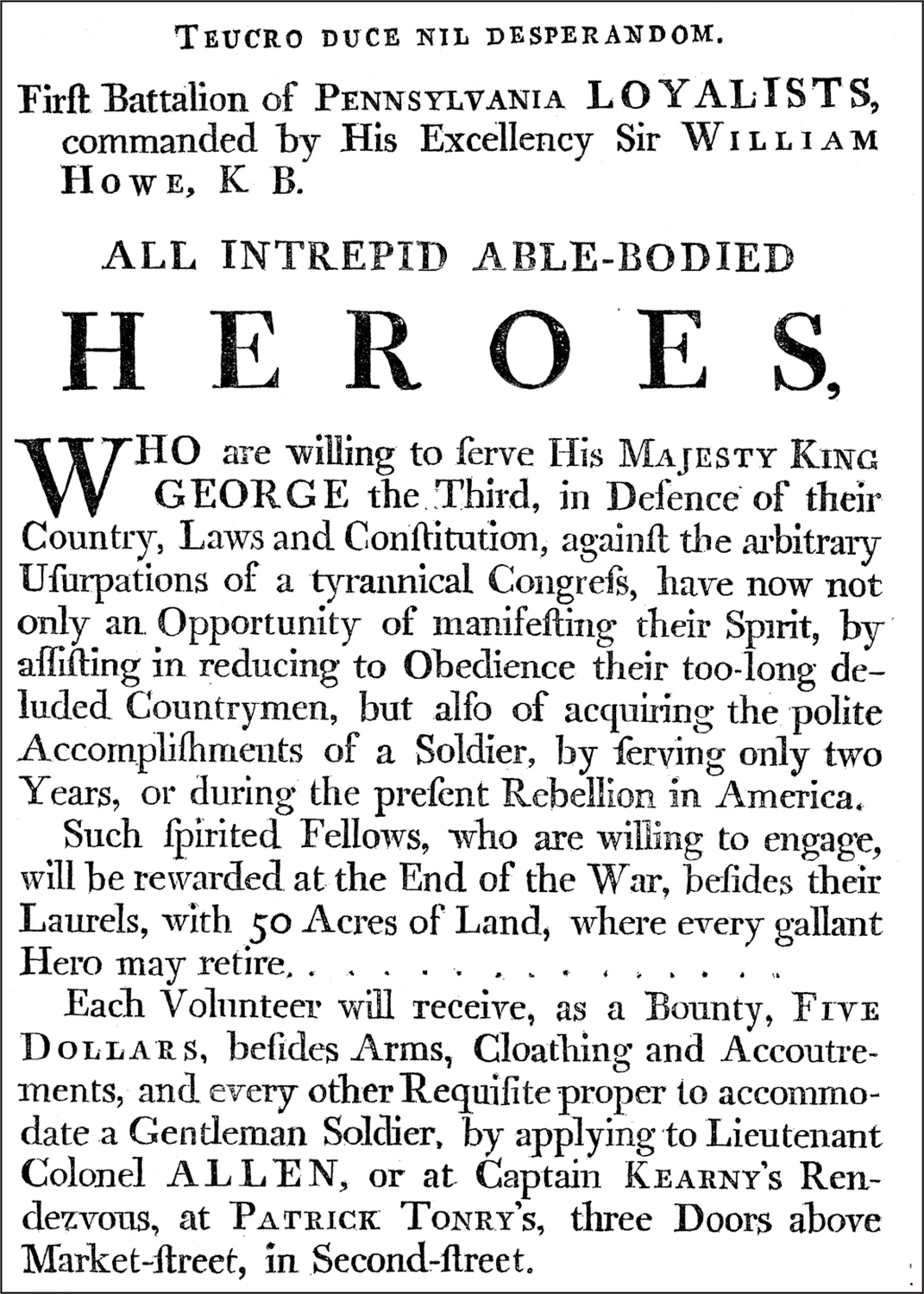

Loyalist Recruiting Poster, 1777 The British army invites a few good men to restore obedience to their “deluded countrymen.” A five dollar signing bonus and a promise of free land await each new recruit, who will also be trained in “the polite Accomplishments of a soldier.” Notice the Latin phrase heading the poster, referencing a military leader in the ancient battle of Troy. What subtle message did that send? The Granger Collection, New York.