Equality and Slavery

Restrictions on political participation did not mean that propertyless people enjoyed no civil rights and liberties. The various state bills of rights applied to all individuals who were free; unfree people were another matter.

The author of the Virginia bill of rights was George Mason, a planter who owned 118 slaves. When he wrote that “all men are by nature equally free and independent,” Mason did not have slaves in mind; he instead was asserting that white Americans were the equals of the British and entitled to equal liberties. Other Virginia legislators, worried about misinterpretations, added a qualifying phrase: that all men “when they enter into a state of society” have inherent rights. As one legislator wrote, with relief, “Slaves, not being constituent members of our society, could never pretend to any benefit from such a maxim.”

One month later, the Declaration of Independence used essentially the same phrase about equality, this time without the modifying clause about entering society. Two state constitutions, Pennsylvania and Massachusetts, also picked it up. In Massachusetts, one town suggested rewording the draft constitution to read “All men, whites and blacks, are born free and equal.” The suggestion was not implemented.

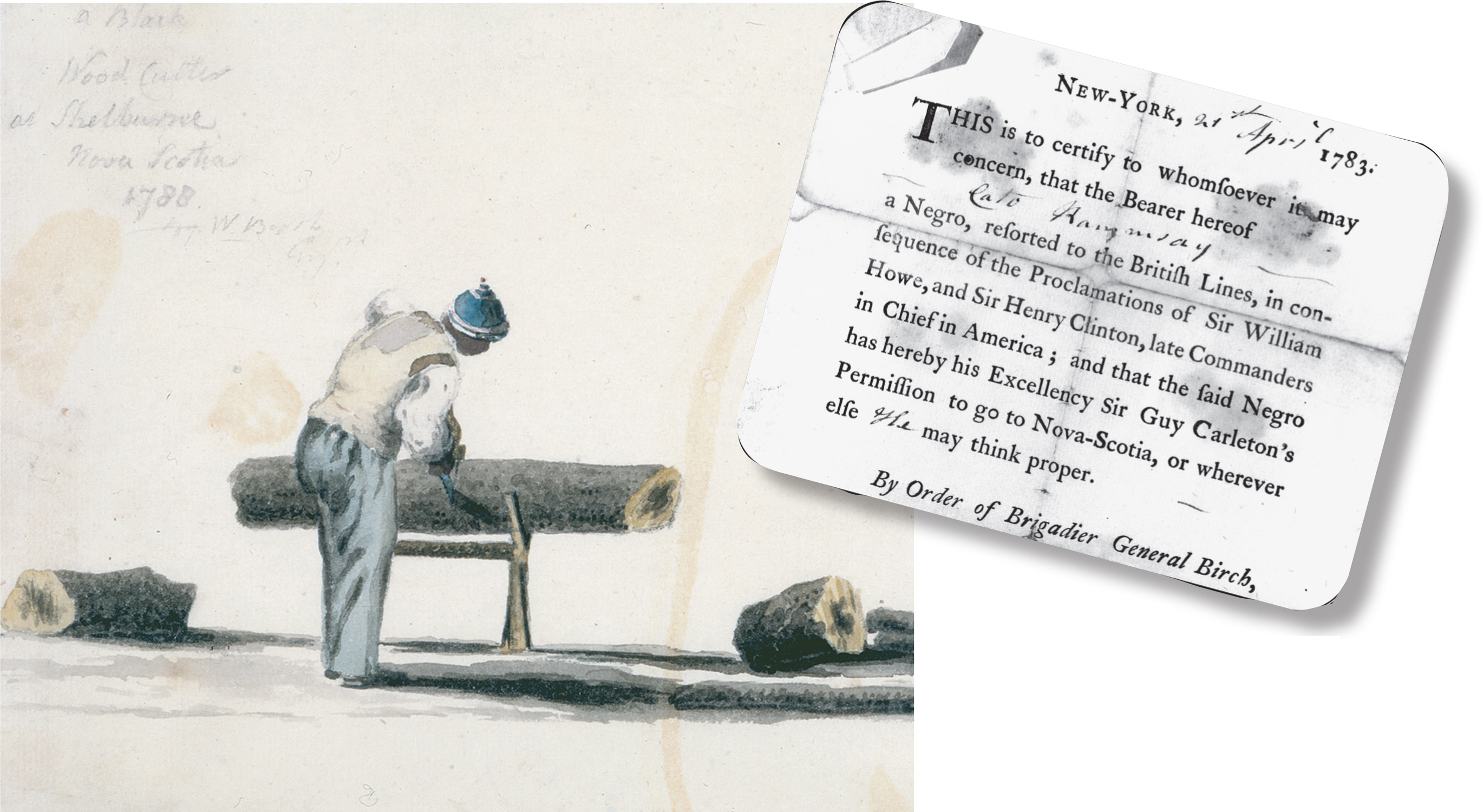

Nevertheless, after 1776, the ideals of the Revolution about natural equality and liberty began to erode the institution of slavery. Often, enslaved blacks led the challenge. In 1777, several Massachusetts slaves petitioned for their “natural & unalienable right to that freedom which the great Parent of the Universe hath bestowed equally on all mankind.” They modestly asked for freedom for their children at age twenty-

Another way to bring the issue before lawmakers was to sue in court. In 1781, a woman called Elizabeth Freeman (Mum Bett) was the first to win freedom in a Massachusetts court, basing her case on the just-

State legislatures acted more slowly. Pennsylvania enacted a gradual emancipation law in 1780, providing that infants born to a slave mother on or after March 1, 1780, would be freed at age twenty-

Rhode Island and Connecticut adopted gradual emancipation laws in 1784; New York waited until 1799 and New Jersey until 1804 to enact theirs. These last were the two northern states with the largest number of slaves: New York in 1800 with 20,000, New Jersey with more than 12,000, whereas in Pennsylvania the number was just 1,700. Gradual emancipation illustrates the tension between radical and conservative implications of republican ideology. Republican government protected people’s liberties and property, yet slaves were both people and property. Gradual emancipation balanced the civil rights of blacks and the property rights of their owners by promising delayed freedom.

South of Pennsylvania, in Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia, where slavery was critical to the economy, emancipation bills were rejected. All three states, however, eased legal restrictions and allowed individual acts of emancipation for adult slaves below the age of forty-

In the deep South—

Although all these instances of emancipation were gradual, small, and certainly incomplete, their symbolic importance was enormous. Every state from Pennsylvania north acknowledged that slavery was fundamentally inconsistent with Revolutionary ideology; “all men are created equal” was beginning to acquire real force as a basic principle.

REVIEW What were the limits of citizenship, rights, and freedom within the various states?