The Requisition of 1785 and Shays’s Rebellion, 1786–1787

Without an impost amendment and with public land sales projected but not yet realized, the confederation again requisitioned the states to contribute revenue. In 1785 the amount requested was $3 million, four times larger than the previous year’s levy. Of this sum, 30 percent was needed for the government’s operating costs, and another 30 percent was earmarked to pay debts owed to foreign lenders, who insisted on payment in gold or silver. The remaining 40 percent was to go to Americans who owned government bonds, the IOUs of the Revolutionary years. A significant slice of that 40 percent represented the interest (but not the principal) owed to army officers for their recently issued “commutation certificates.” This was a tax that, if collected, was going to hurt.

At this time, states were struggling under state tax levies. The legislatures of several states without major ports (and the import duties that ports generated) were already pressing higher tax bills onto their farmer citizens in order to retire state debts from the Revolution. New Jersey and Connecticut fit this profile, and both state legislatures voted to ignore the confederation’s requisition. In New Hampshire, town meetings voted to refuse to pay, because they could not. In 1786, two hundred armed insurgents surrounded the New Hampshire capitol to protest the taxes but were driven off by an armed militia. The shocked assemblymen backed off from an earlier order to haul delinquent taxpayers into courts. Rhode Island, North Carolina, and Georgia responded to their constituents’ protests by issuing abundant amounts of paper money and allowing taxes to be paid in greatly depreciated currency.

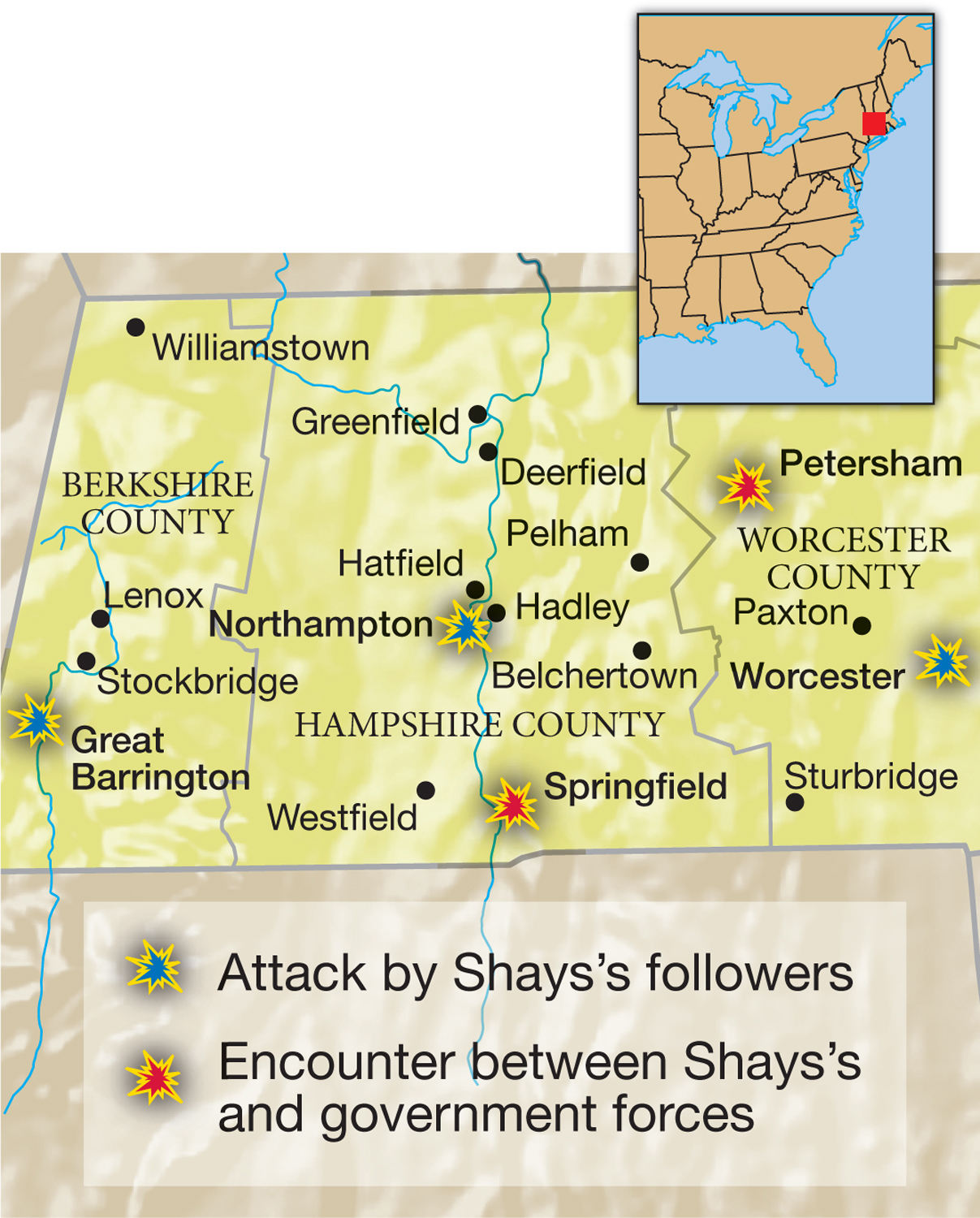

Nowhere were the tensions so extreme as in Massachusetts. For four years in a row, a fiscally conservative legislature, dominated by the coastal commercial centers, had passed tough tax laws to pay state creditors who required payment in hard money, not cheap paper. Then in March 1786, the legislature in Boston loaded the federal requisition onto the bill. In June, farmers in southeastern Massachusetts marched on a courthouse in an effort to close it down, and petitions of complaint about oppressive taxation poured in from the western two-

Still unheard in Boston, the dissidents targeted the county courts, the local symbol of state authority. In the fall of 1786, several thousand armed men shut down courthouses in six counties; sympathetic local militias did not intervene. The insurgents were not predominantly poor or debt-

The governor of Massachusetts, James Bowdoin, once a protester against British taxes, now characterized the western dissidents as illegal rebels. He vilified Shays as the chief leader, and a Boston newspaper claimed that Shays planned to burn Boston to the ground and overthrow the government. Another former radical, Samuel Adams, took the extreme position that “the man who dares rebel against the laws of a republic ought to suffer death.” Those aging revolutionaries were not prepared to believe that representatives in a state legislature could seem to be as oppressive as monarchs. The dissidents challenged the assumption that popularly elected governments would always be fair and just.

Members of the Continental Congress had much to worry about. In nearly every state, the requisition of 1785 spawned some combination of crowd protests, demands for inflationary paper money, and anger at state authorities and alleged money speculators. The Massachusetts insurgency was the worst episode, and it seemed to be spinning out of control. In October, the congress attempted to triple the size of the federal army, but fewer than 100 men enlisted. So Governor Bowdoin raised a private army, gaining the services of some 3,000 men with pay provided by wealthy and fearful Boston merchants.

In January 1787, the insurgents learned of the private army marching west from Boston, and 1,500 of them moved swiftly to capture a federal armory in Springfield to obtain weapons. But a militia band loyal to the state government beat them to the weapons facility and met their attack with gunfire; 4 rebels were killed and another 20 wounded. The final and bloodless encounter came at Petersham, where Bowdoin’s army surprised the rebels and took several hundred of them prisoner. In the end, 2 men were executed for rebellion; 16 more sentenced to hang were reprieved at the last moment on the gallows. Some 4,000 men gained leniency by confessing their misconduct and swearing an oath of allegiance to the state. A special Disqualification Act prohibited the penitent rebels from voting, holding public office, serving on juries, working as schoolmasters, or operating taverns for up to three years.

Shays’s Rebellion caused leaders throughout the country to worry about the confederation’s ability to handle civil disorder. Inflammatory Massachusetts newspapers wrote about bloody mob rule spreading to other states. New York lawyer John Jay wrote to George Washington, “Our affairs seem to lead to some crisis, some revolution—

REVIEW What were the most important factors in the failure of the Articles of Confederation?