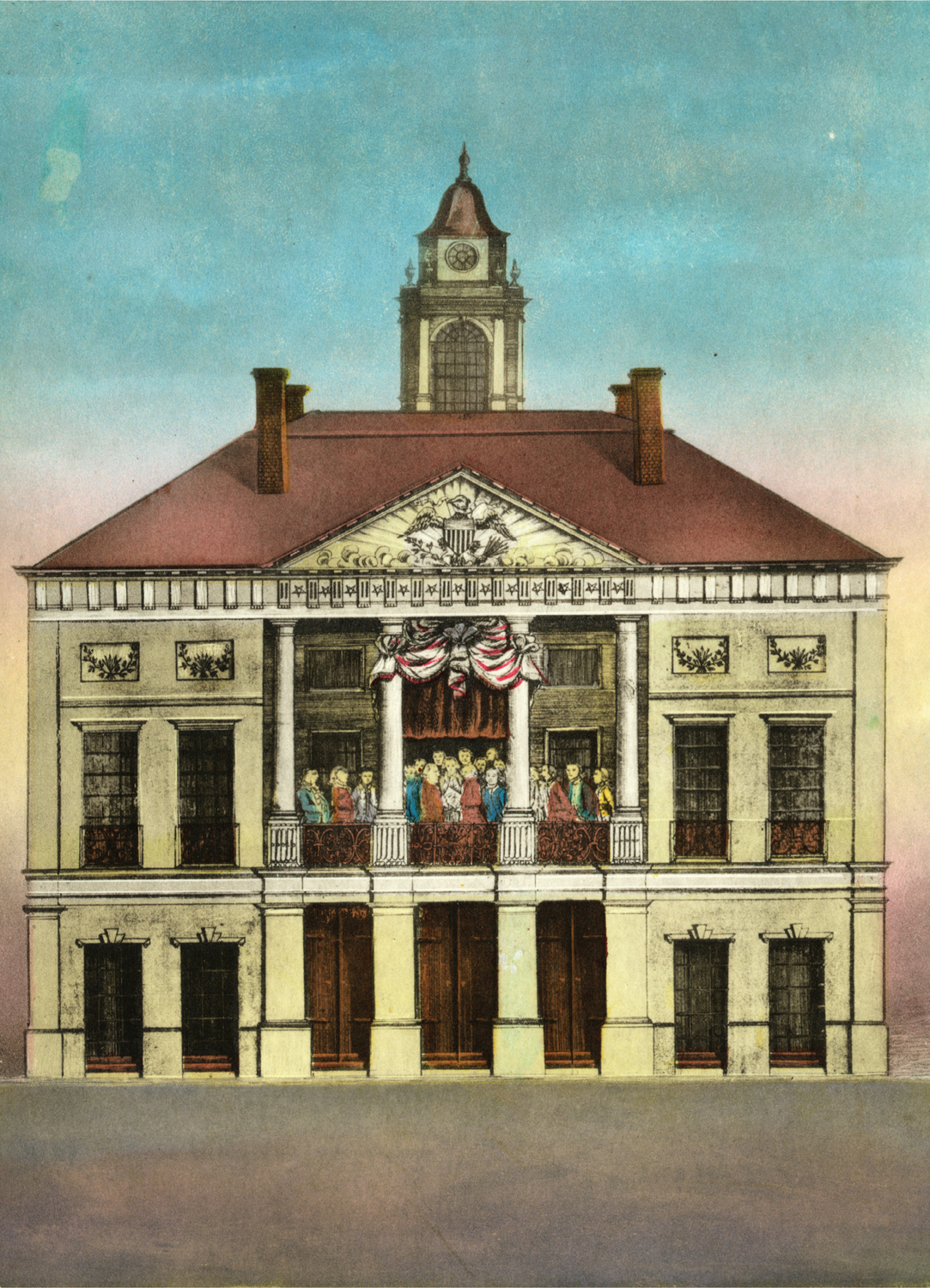

Washington Inaugurates the Government

George Washington was elected president in February 1789 by a unanimous vote of the electoral college. (John Adams got just half as many votes; he became vice president, but his pride was wounded.) Washington perfectly embodied the republican ideal of disinterested, public-

Once in office, Washington calculated his moves, knowing that every step set a precedent and that any misstep could be dangerous for the fragile government. Congress debated a title for Washington, ranging from “His Highness” to “His Majesty, the President”; Washington favored “His High Mightiness.” But in the end, republican simplicity prevailed. The final title was simply “President of the United States of America,” and the established form of address became “Mr. President,” a subdued yet dignified title reserved for property-

Washington’s genius in establishing the presidency lay in his capacity for implanting his own reputation for integrity into the office itself. In the political language of the day, he was “virtuous,” meaning that he took pains to elevate the public good over private interest and projected honesty and honor over ambition. He remained aloof, resolute, and dignified, to the point of appearing wooden at times. He encouraged pomp and ceremony to create respect for the office, traveling with six horses to pull his coach, hosting formal balls, and surrounding himself with uniformed servants. He even held weekly “levees,” as European monarchs did, hour-

Washington chose talented and experienced men to preside over the newly created Departments of War, Treasury, and State. For the Department of War, Washington selected General Henry Knox, former secretary of war in the confederation government. For the Treasury—

Soon Washington began to hold regular meetings with these men, thereby establishing the precedent of a presidential cabinet. (Vice President John Adams was not included; his only official duty, to preside over the Senate, he found “a punishment.” To his wife he complained, “My country has in its wisdom contrived for me the most insignificant office.”) No one anticipated that two decades of party turbulence would emerge from the brilliant but explosive mix of Washington’s first cabinet.