Conducting Meetings

Printed Page 61-69

Conducting Meetings

To watch a tutorial on using helpful online tools to schedule meetings, go to Ch. 4 > Additional Resources > Tutorials: macmillanhighered.com/ launchpad/techcomm11e.

Collaboration involves meetings. Whether you are meeting live in a room on campus or using videoconferencing tools, the five aspects of meetings discussed in this section can help you use your time productively and produce the best possible document.

LISTENING EFFECTIVELY

Participating in a meeting involves listening and speaking. If you listen carefully to other people, you will understand what they are thinking and you will be able to speak knowledgeably and constructively. Unlike hearing, which involves receiving and processing sound waves, listening involves understanding what the speaker is saying and interpreting the information.

Listening Effectively

Follow these five steps to improve your effectiveness as a listener.

- Pay attention to the speaker. Look at the speaker, and don’t let your mind wander.

- Listen for main ideas. Pay attention to phrases that signal important information, such as “What I’m saying is . . .” or “The point I’m trying to make is . . . .”

- Don’t get emotionally involved with the speaker’s ideas. Even if you disagree, continue to listen. Keep an open mind. Don’t stop listening in order to plan what you are going to say next.

- Ask questions to clarify what the speaker said. After the speaker finishes, ask questions to make sure you understand. For instance, “When you said that each journal recommends different protocols, did you mean that each journal recommends several protocols or that each journal recommends a different protocol?”

- Provide appropriate feedback. The most important feedback is to look into the speaker’s eyes. You can nod your approval to signal that you understand what he or she is saying. Appropriate feedback helps assure the speaker that he or she is communicating effectively.

SETTING YOUR TEAM’S AGENDA

It’s important to get your team off to a smooth start. In the first meeting, start to define your team’s agenda.

Setting Your Team’s Agenda

Carrying out these eight tasks will help your team work effectively and efficiently.

- Define the team’s task. Every team member has to agree on the task, the deadline, and the approximate length of the document. You also need to agree on more conceptual points, including the document’s audience, purpose, and scope.

- Choose a team leader. This person serves as the link between the team and management. (In an academic setting, the team leader represents the team in communicating with the instructor.) The team leader also keeps the team on track, leads the meetings, and coordinates communication among team members.

- Define tasks for each team member. There are three main ways to divide the tasks: according to technical expertise (for example, one team member, an engineer, is responsible for the information about engineering), according to stages of the writing process (one team member contributes to all stages, whereas another participates only during the planning stage), or according to sections of the document (several team members work on the whole document but others work only on, say, the appendixes). People will likely assume informal roles, too. One person might be good at clarifying what others have said, another at preventing arguments, and another at asking questions that force the team to reevaluate its decisions.

- Establish working procedures. Before starting to work, collaborators need answers—in writing, if possible—to the following questions:

—When and where will we meet?

—What procedures will we follow in the meetings?

—What tools will we use to communicate with other team members, including the leader, and how often will we communicate?

- Establish a procedure for resolving conflict productively. Disagreements about the project can lead to a better product. Give collaborators a chance to express ideas fully and find areas of agreement, and then resolve the conflict with a vote.

- Create a style sheet. A style sheet defines the characteristics of the document’s writing style. For instance, a style sheet states how many levels of headings the document will have, whether it will have lists, whether it will have an informal tone (for example, using “you” and contractions), and so forth. If all collaborators draft using a similar writing style, the document will need less revision. And be sure to use styles, as discussed in Chapter 3, to ensure a consistent design for headings and other textual features.

- Establish a work schedule. For example, for a proposal to be submitted on February 10, you might aim to complete the outline by January 25, the draft by February 1, and the revision by February 8. These dates are called milestones.

- Create evaluation materials. Team members have a right to know how their work will be evaluated. In college, students often evaluate themselves and other team members. In the working world, managers are more likely to do the evaluations.

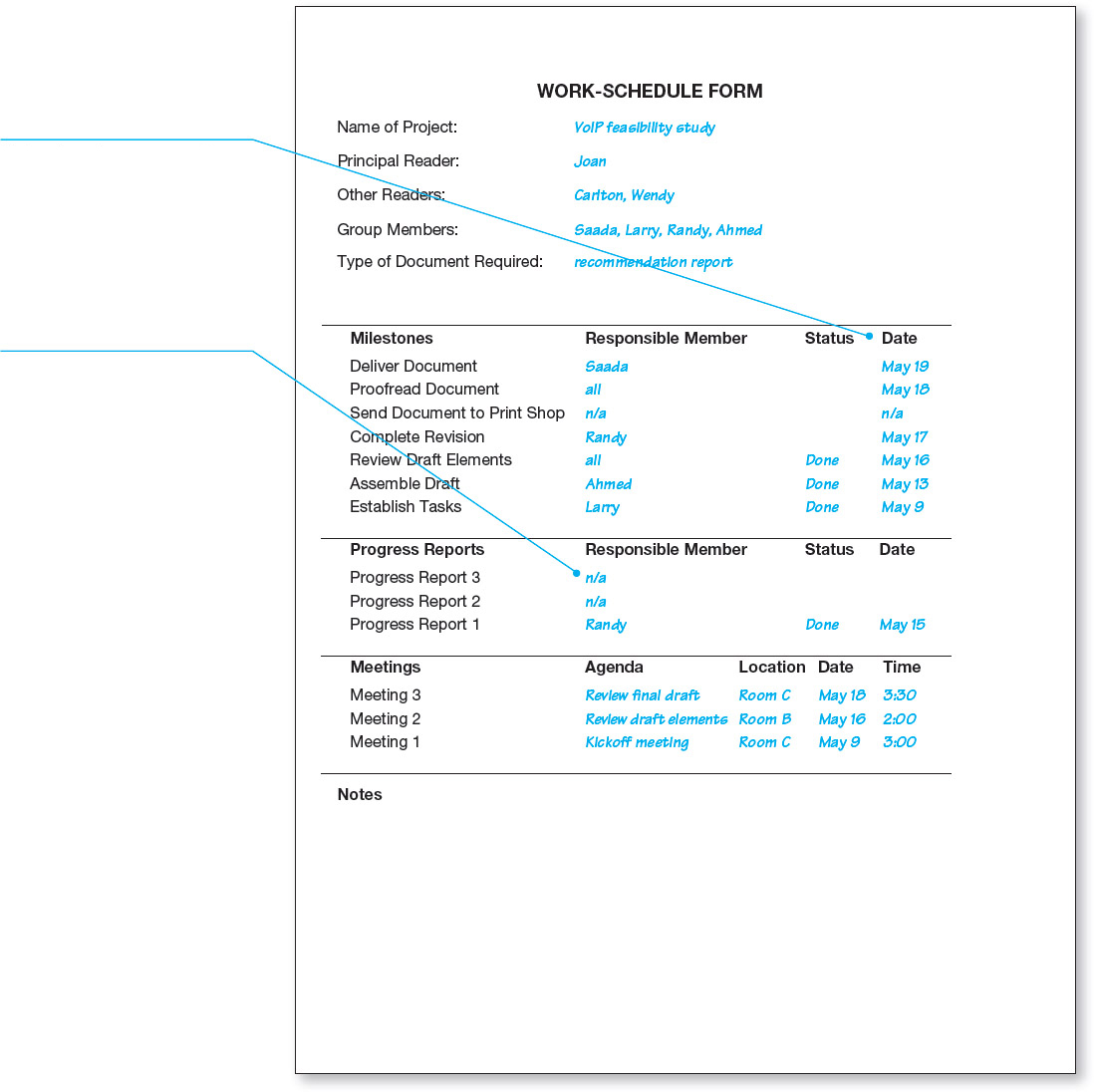

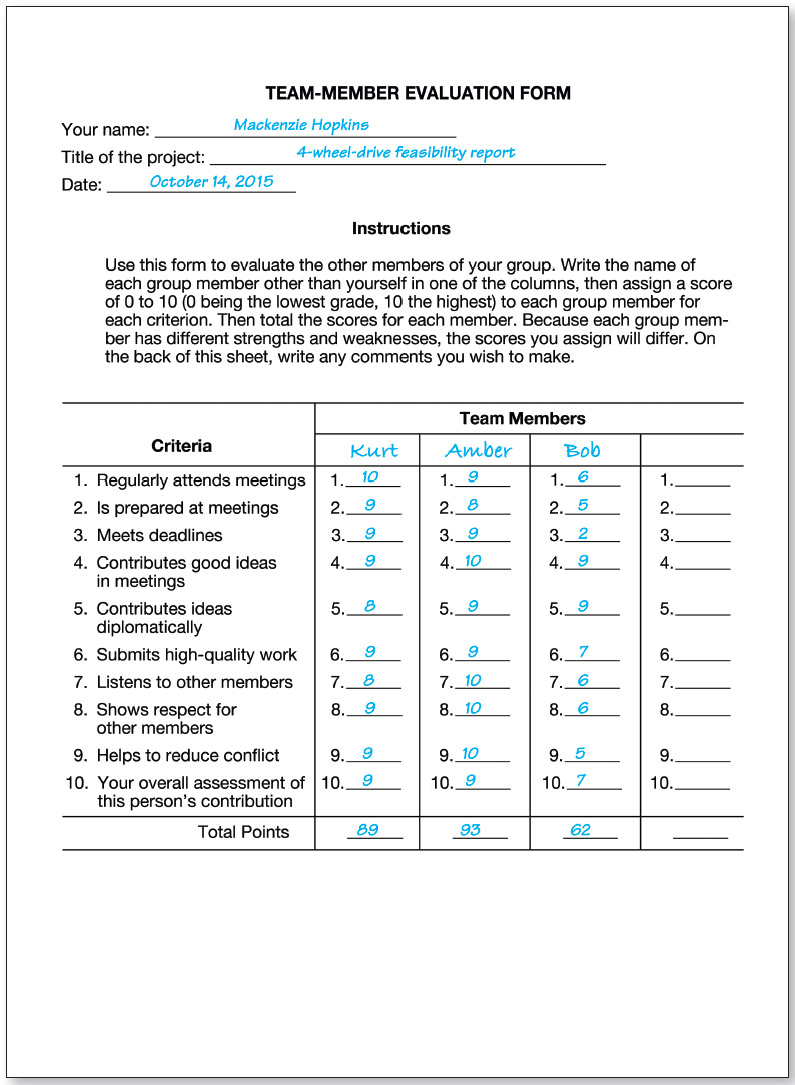

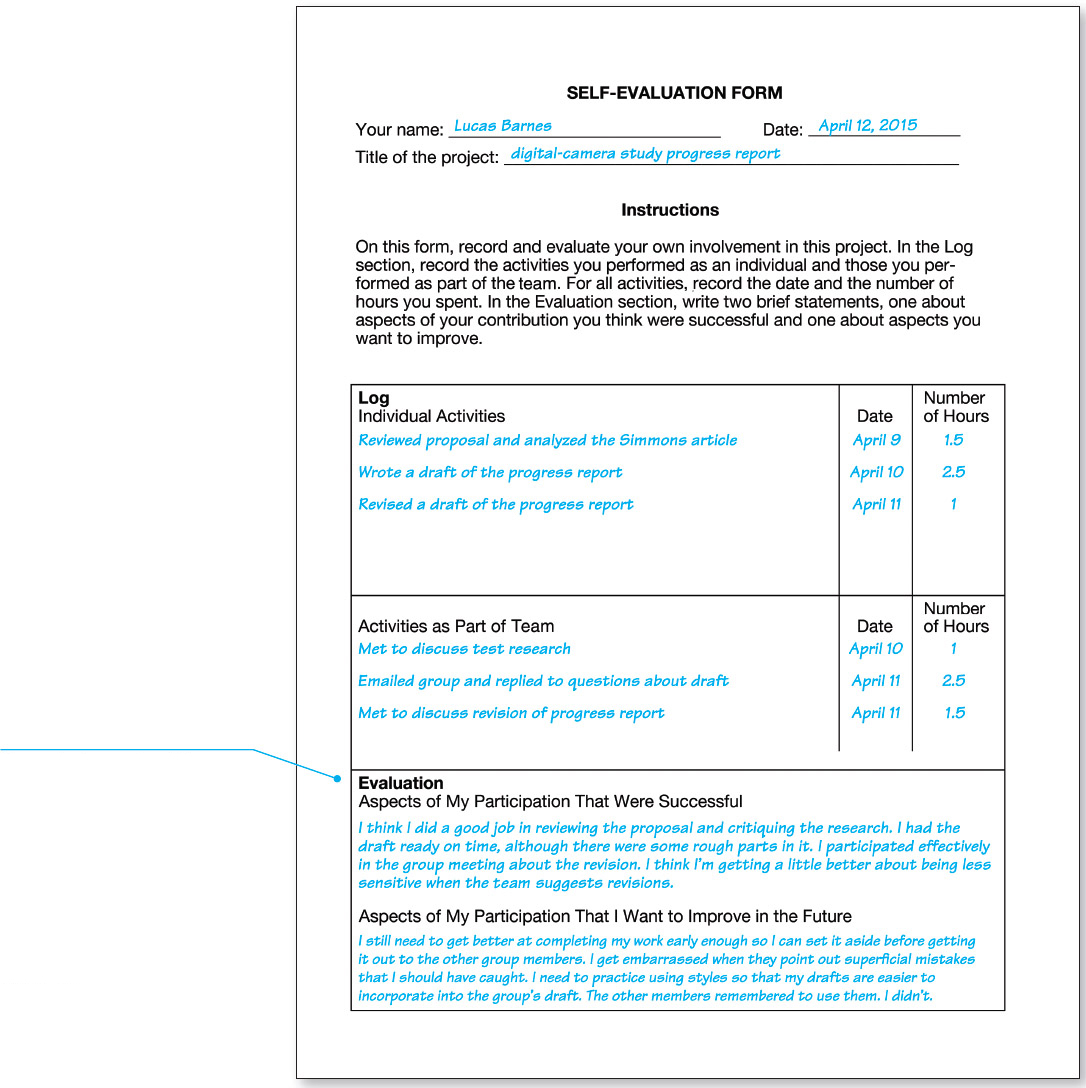

Figure 4.2 shows a work-schedule form. Figure 4.3 shows a team member evaluation form, and Figure 4.4 shows a self-evaluation form.

Download blank copies of these forms.

Notice that milestones sometimes are presented in reverse chronological order; the delivery-date milestone, for instance, comes first. On other forms, items are presented in normal chronological order.

The form includes spaces for listing the person responsible for each milestone and progress report and for stating the progress toward each milestone and progress report.

Mackenzie gives high grades to Kurt and Amber but low grades to Bob. If Kurt and Amber agree with Mackenzie’s assessment of Bob’s participation, the three of them should meet with Bob to discuss why his participation has been weak and to consider ways for him to improve.

The evaluation section of the form is difficult to fill out, but it can be the most valuable section for you in assessing your skills in collaborating. When you get to the second question, be thoughtful and constructive. Don’t merely say that you want to improve your skills in using the software. And don’t just write “None.”

ETHICS NOTE

PULLING YOUR WEIGHT ON COLLABORATIVE PROJECTS

Collaboration involves an ethical dimension. If you work hard and well, you help the other members of the team. If you don’t, you hurt them.

You can’t be held responsible for knowing and doing everything, and sometimes unexpected problems arise in other courses or in your private life that prevent you from participating as actively and effectively as you otherwise could. When problems occur, inform the other team members as soon as possible. For instance, call the team leader as soon as you realize you will have to miss a meeting. Be honest about what happened. Suggest ways you might make up for missing a task. If you communicate clearly, the other team members are likely to cooperate with you.

If you are a member of a team that includes someone who is not participating fully, keep records of your attempts to get in touch with that person. When you do make contact, you owe it to that person to try to find out what the problem is and suggest ways to resolve it. Your goal is to treat that person fairly and to help him or her do better work, so that the team will function more smoothly and more effectively.

CONDUCTING EFFICIENT MEETINGS

Human communication is largely nonverbal. That is, although people communicate through words and through the tone, rate, and volume of their speech, they also communicate through body language. For this reason, meetings provide the most information about what a person is thinking and feeling—and the best opportunity for team members to understand one another.

For a discussion of meeting minutes, see Ch. 17.

To help make meetings effective and efficient, team members should arrive on time and stick to the agenda. One team member should serve as secretary, recording the important decisions made at the meeting. At the end of the meeting, the team leader should summarize the team’s accomplishments and state the tasks each team member is to perform before the next meeting. If possible, the secretary should give each team member this informal set of meeting minutes.

COMMUNICATING DIPLOMATICALLY

Because collaborating can be stressful, it can lead to interpersonal conflict. People can become frustrated and angry with one another because of personality clashes or because of disputes about the project. If the project is to succeed, however, team members have to work together productively. When you speak in a team meeting, you want to appear helpful, not critical or overbearing.

CRITIQUING A TEAM MEMBER’S WORK

In your college classes, you probably have critiqued other students’ writing. In the workplace, you will do the same sort of critiquing of notes and drafts written by other team members. Knowing how to do it without offending the writer is a valuable skill.

Communicating Diplomatically

- These seven suggestions for communicating diplomatically will help you communicate effectively.

- Listen carefully, without interrupting. See the Guidelines box on page 62.

- Give everyone a chance to speak. Don’t dominate the discussion.

- Avoid personal remarks and insults. Be tolerant and respectful of other people’s views and working methods. Doing so is right—and smart: if you anger people, they will go out of their way to oppose you.

- Don’t overstate your position. A modest qualifier such as “I think” or “it seems to me” is an effective signal to your listeners that you realize that everyone might not share your views.

OVERBEARING My plan is a sure thing; there’s no way we’re not going to kill Allied next quarter. DIPLOMATIC I think this plan has a good chance of success: we’re playing off our strengths and Allied’s weaknesses. Note that in the diplomatic version, the speaker says “this plan,” not “my plan.”

- Don’t get emotionally attached to your own ideas. When people oppose you, try to understand why. Digging in is usually unwise—unless it’s a matter of principle—because, although it’s possible that you are right and everyone else is wrong, it’s not likely.

- Ask pertinent questions. Bright people ask questions to understand what they hear and to connect it to other ideas. Asking questions also encourages other team members to examine what they hear.

- Pay attention to nonverbal communication. Bob might say that he understands a point, but his facial expression might show that he doesn’t. If a team member looks confused, ask him or her about it. A direct question is likely to elicit a statement that will help the team clarify its discussion.

Critiquing a Colleague’s Work

Most people are very sensitive about their writing. Following these three suggestions for critiquing writing will increase the chances that your colleague will consider your ideas positively.

- Start with a positive comment. Even if the work is weak, say, “You’ve obviously put a lot of work into this, Joanne. Thanks.” Or, “This is a really good start. Thanks, Joanne.”

- Discuss the larger issues first. Begin with the big issues, such as organization, development, logic, design, and graphics. Then work on smaller issues, such as paragraph development, sentence-level matters, and word choice. Leave editing and proofreading until the end of the process.

- Talk about the document, not the writer.

RUDE You don’t explain clearly why this criterion is relevant. BETTER I’m having trouble understanding how this criterion relates to the topic. Your goal is to improve the quality of the document you will submit, not to evaluate the writer or the draft. Offer constructive suggestions.

RUDE Why didn’t you include the price comparisons here, as you said you would? BETTER I wonder if the report would be stronger if we included the price comparisons here. - In the better version, the speaker focuses on the goal (to create an effective report) rather than on the writer’s draft. Also, the speaker qualifies his recommendation by saying, “I wonder if . . . .” This approach sounds constructive rather than boastful or annoyed.