Crafting a Persuasive Argument

Printed Page 175-182

Crafting a Persuasive Argument

Persuasion is important, whether you wish to affect a reader’s attitude or merely present information clearly. To make a persuasive case, you must identify the elements of your argument, use the right kinds of evidence, consider opposing viewpoints, appeal to emotions responsibly, decide where to state your claim, and understand the role of culture in persuasion.

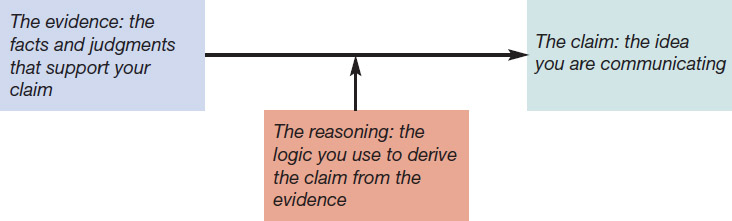

A persuasive argument has three main elements:

The claim is the conclusion you want your readers to accept. For example, your claim might be that your company should institute flextime, a scheduling approach that gives employees some flexibility in when they begin and end their workdays. You want your readers to agree with this idea and to take the next steps toward instituting flextime.

The evidence is the information you want your readers to consider. For the argument about flextime, the evidence might include the following:

- The turnover rate of our employees with young children is 50 percent higher than that of our employees without young children. The turnover rate for female employees with young children is double that of all employees without young children.

- At exit interviews, 40 percent of our employees with young children stated that they quit so that they could be home for their school-age children.

- Replacing a staff-level employee costs us about one-half the employee’s annual salary; replacing a professional-level employee costs a whole year’s salary.

- Other companies have found that flextime significantly decreases turnover among employees with young children.

- Other companies have found that flextime has additional benefits and introduces no significant problems.

The reasoning is the logic you use to connect the evidence to your claim. In the discussion of flextime, the reasoning involves three links:

- At other companies, flextime appears to have reduced the turnover problem among employees with young children.

- Our company is similar to these other companies.

- Flextime is therefore likely to prove helpful at our company.

For advice on evaluating information from the Internet, see Ch. 6.

People most often react favorably to four kinds of evidence: “commonsense” arguments, numerical data, examples, and expert testimony.

- “Commonsense” arguments. Here, commonsense means “Most people would think that . . . .” The following sentence presents a commonsense argument that flextime is a good idea:

Flextime makes sense because it gives people more control over how they plan their schedules.

A commonsense argument says, “I don’t have hard evidence to support my conclusion, but it stands to reason that . . . .” In this case, the argument is that people like to have as much control over their time as possible. If your audience’s commonsense viewpoints match yours, your argument is likely to be persuasive.

- Numerical data. Numerical data—statistics—are generally more persuasive than commonsense arguments.

Statistics drawn from the personnel literature (McClellan, 2013) show that, among Fortune 500 companies, flextime decreases turnover by 25 to 35 percent among employees with young children.

Notice that the writer states that the study covered many companies, not just one or a handful. If the sample size were small, the claim would be much less persuasive. (The discussion of logical fallacies later in this chapter explains such hasty generalizations.)

- Examples. An example makes an abstract point more concrete and therefore more vivid and memorable.

Mary Saunders tried for weeks to arrange for child care for her two preschoolers that would enable her to start work at 7 A.M., as required at her workplace. The best she could manage was having her children stay with a nonlicensed provider. When conditions at that provider led to ear infections in both her children, Mary decided that she could no longer continue working.

Examples are often used along with numerical data. The example above gives the problem a human dimension, but the argument also requires numerical data to show that the problem is part of a pattern, not an isolated event.

- Expert testimony. A message from an expert is more persuasive than the same message from someone without credentials. A well-researched article on flextime written by a respected business scholar in a reputable business journal is likely to be persuasive. When you make arguments, you will often cite expert testimony from published sources or interviews you have conducted.

Figure 8.3, excerpts from a white paper published by McAfee, the computer-security company, shows a portion of an argument that combines several of these types of evidence. A white paper is an argument, typically 10–20 pages long, that a company’s product or service will solve a technological or business challenge in an industry. The readers of white papers are technical experts who implement technology and managers who make purchasing decisions.

This white paper was written by Dmitri Alperovitch, McAfee’s Vice President for Threat Research. A highly regarded security expert, Alperovitch has won numerous awards, including selection in 2013 as one of MIT Technology Review’s Top 35 Innovators Under 35. This first paragraph, with its use of “I” and the references to projects with which Alperovitch is associated, presents him as an expert. The logic is that if he thinks these security threats are credible, you should, too.

Paragraph 2 presents a series of examples of what the writer calls an “unprecedented transfer of wealth.”

Why haven’t we heard more about this transfer of wealth? The writer answers the question using commonsense evidence: we haven’t heard about it because victims of these security attacks keep quiet, fearing that the bad publicity will undermine the public’s trust in them.

The writer presents additional examples of the nature and scope of the attacks. In the rest of the 14-page white paper, he presents statistics and examples describing the 71 attacks that he is calling Operation Shady RAT. The evidence adds up to a compelling argument that the threat is real and serious, and McAfee is the organization you should trust to help you protect yourself from it.

Figure 8.3 Using Different Types of Evidence in an Argument

When you present an argument, you need to address opposing points of view. If you don’t, your opponents will conclude that your proposal is flawed because it doesn’t address problems that they think are important. In meeting the skeptical or hostile reader’s possible objections to your case, you can use one of three tactics, depending on the situation:

- The opposing argument is based on illogical reasoning or on inaccurate or incomplete facts. You can counter the argument that flextime increases utility bills by citing unbiased research studies showing that it does not.

- The opposing argument is valid but is less powerful than your own. If you can show that the opposing argument makes sense but is outweighed by your own argument, you will appear to be a fair-minded person who understands that reality is complicated. You can counter the argument that flextime reduces carpooling opportunities by showing that only 3 percent of your employees currently use carpooling and that three-quarters of these employees favor flextime anyway because of its other advantages.

- The two arguments can be reconciled. If an opposing argument is not invalid or clearly inferior to your own, you can offer to study the situation thoroughly to find a solution that incorporates the best from each argument. For example, if flextime might cause serious problems for your company’s many carpoolers, you could propose a trial period during which you would study several ways to help employees find other carpooling opportunities. If the company cannot solve the problem or if most of the employees prefer the old system, you would switch back to it. This proposal can remove much of the threat posed by your ideas.

When you address an opposing argument, be gracious and understated. Focus on the argument, not on the people who oppose you. If you embarrass or humiliate them, you undermine your own credibility and motivate your opponents to continue opposing you.

There is no one best place in your document to address opposing arguments. In general, however, if you know that important readers hold opposing views, address those views relatively early. Your goal is to show all your readers that you are a fair-minded person who has thought carefully about the subject and that your argument is stronger than the opposing arguments.

Writers sometimes appeal to the emotions of their readers. Writers usually combine emotional appeals with appeals to reason. For example, an argument that we ought to increase foreign aid to drought-stricken African countries might describe (and present images of) the human plight of the victims but also include reason-based sections about the extent of the problem, the causes, the possible solutions, and the pragmatic reasons we might want to increase foreign aid.

When you use emotional appeals, do not overstate or overdramatize them, or you will risk alienating readers. Try to think of additional kinds of evidence to present that will also help support your claim. Figure 8.4 shows a brief argument that relies on an emotional appeal.

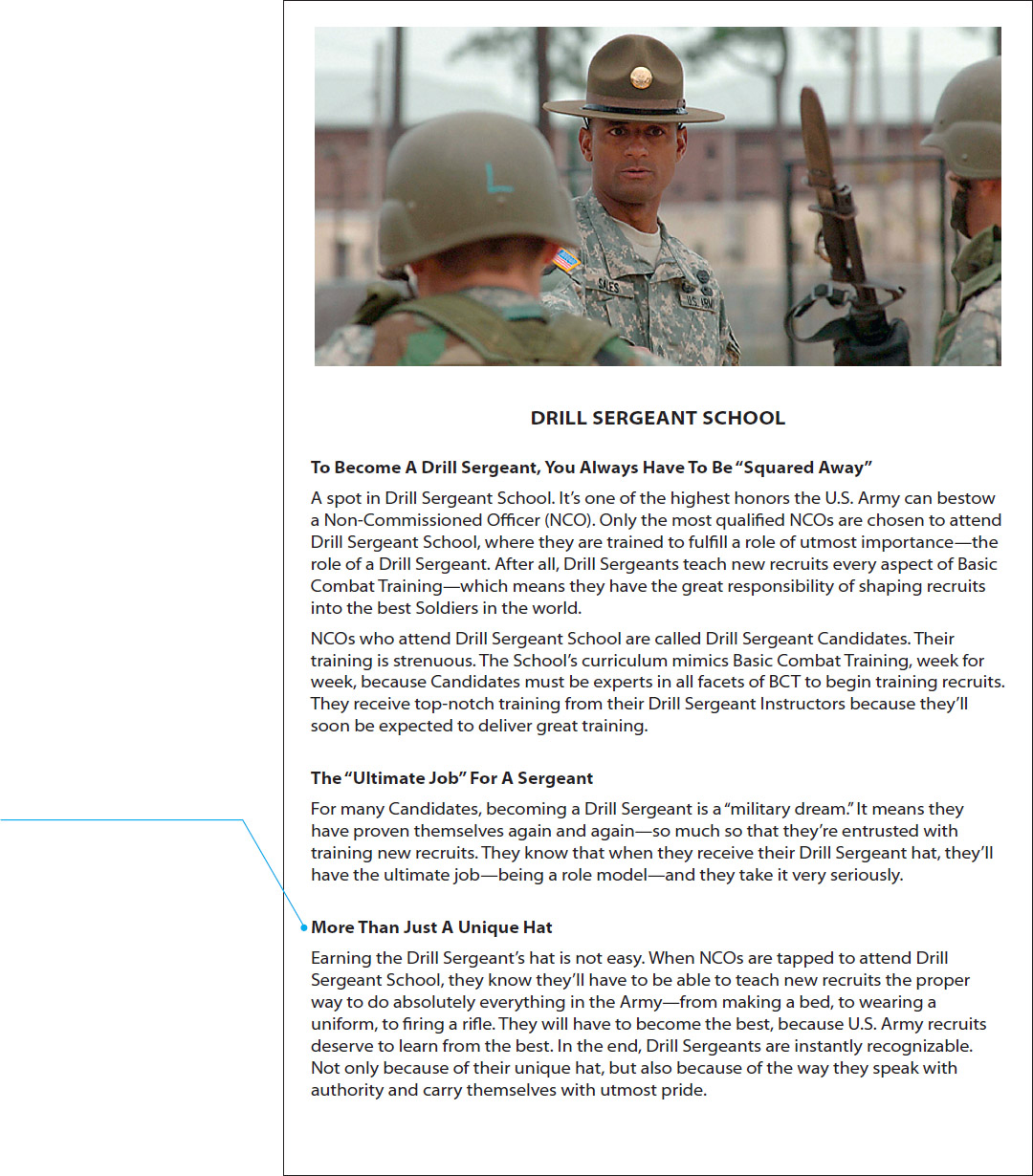

This excerpt from the Army recruitment site, GoArmy.com, describes the Drill Sergeant School.

The photo and the text present a reasonable mix of information and emotion. The site provides facts about how drill sergeants are chosen and trained and the responsibilities they carry. The lives of drill sergeants are not always heroic and romantic; they have to teach recruits how to make their beds, for instance. But the discussion is clearly meant to appeal to the emotions of people who are considering joining the Army with the goal of becoming drill sergeants. The passage repeatedly refers to drill sergeants as being “the best.” Only a select few NCOs can become drill sergeants. They become role models, carrying themselves with pride.

Everyone likes to think of himself or herself as a special person doing an important job. As long as the facts that accompany an emotional appeal are accurate and presented honestly, an emotional appeal is responsible.

Figure 8.4 An Argument Based on an Emotional Appeal

In most cases, the best place to state your claim is at the start of the argument. Then provide the evidence and, if appropriate, the reasoning. Sometimes, however, it is more effective to place the claim after the evidence and the reasoning. This indirect structure works best if a large number of readers oppose your claim. If you present your claim right away, these readers might become alienated and stop paying attention. You want a chance to present your evidence and your reasoning without causing this kind of undesirable reaction.

Read more about writing for people from other cultures in Ch. 5.

If you are making a persuasive argument to readers from another culture, keep in mind that cultures differ significantly not only in matters such as business customs but also in their most fundamental values. These differences can affect persuasive writing. Culture determines both what makes an argument persuasive and how arguments are structured:

- What makes an argument persuasive. Statistics and experimental data are fundamental kinds of evidence in the West, but testimony from respected authority figures can be much more persuasive in the East.

- How to structure an argument. In a Western culture, the claim is usually presented up front. In an Eastern culture, it is likely to be delayed or to remain unstated but implied.

When you write for an audience from another culture, use two techniques:

- Study that culture, and adjust the content, structure, and style of your arguments to fit it.

- Include in your budget the cost of having important documents reviewed and edited by a person from the target culture. Few people are experts on cultures other than their own.