Jon Ronson The Hunger Games

Instructor's Notes

- The “Make Connections” activity can be used as a discussion board prompt by clicking on “Add to This Unit,”" selecting “Create New,” choosing “Discussion Board,” and then pasting the “Make Connections” activity into the text box.

- The basic features (“Analyze and Write”) activities following this reading, as well as an autograded multiple-

choice quiz, a summary activity with a sample summary as feedback, and a synthesis activity for this reading, can be assigned by clicking on the “Browse Resources for the Unit” button or navigating to the “Resources” panel."

71

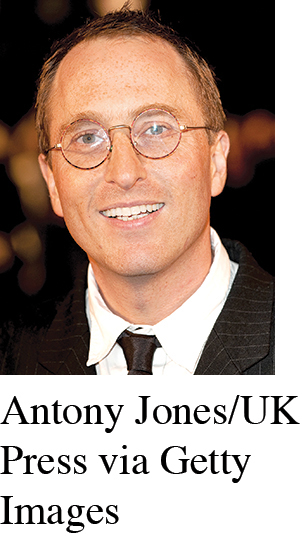

JON RONSON has written a number of books, including The Psychopath Test: A Journey Through the Madness Industry (2011) and Out of the Ordinary: True Tales of Everyday Craziness (2006). Trained in media studies, Ronson regularly contributes profiles and documentaries to The Guardian newspaper, The New York Times Book Review, BBC Radio 4 in the United Kingdom, and This American Life in the United States. The film The Men Who Stare at Goats (2009) was based on Ronson’s 2004 book of the same name, and Ronson himself co-

As you read,

notice that Ronson makes three moves in the opening paragraph: beginning with a description, giving a brief anecdote, and then telling us what he thinks.

how do these moves help interest readers in the subject? Which move works especially well to arouse your interest?

1

H ere is a mountain of corned-

2

But a sense of fatalistic doom pervades the air. This is because one man is quite simply predestined to win. His name is Joey Chestnut, and he’s a charismatic, sweet-

3

About 200 people have turned up to watch him try to break his own corned-

4

The fans are mostly ignoring Joey’s challengers. There’s the world number two, Pat “Deep Dish” Bertoletti, muscular, wiry, a Mohawk haircut, almost always the bridesmaid, rarely the bride. There’s a beautiful woman in her twenties named Maria Edible—

72

5

I approach Joey. “Who’s that boy?” I whisper.

6

“Matt Stonie,” he whispers back. “He’s new. He’s good. I watched a YouTube video of him in training. You hear his mother in the background encouraging him. When I saw that, I thought, ‘Why would she be encouraging him? There must be something wrong with him for her to be encouraging him to eat.’” Joey lowers his voice. “Apparently when he was 15 he was anorexic.”. . .

7

Our conversation is interrupted by the emcee, Rich Shea, who is telling the audience how blessed we Americans are to have the freedom to eat as many corned-

8

For two days now, I’ve been listening to Joey extol the sport as a sensei would a martial art. He has told me, for example, how he has studied the ingestion techniques of snakes: “Their muscles are contracting constantly. You’ll see when I’m eating, there’s a constant weird up-

Competitive eating is, of course, a manifestation of the American urge to turn absolutely everything, even something as elemental as eating, into a competition.

9

So after all of Joey’s talk of science and preparation, I was imagining the corned-

10

It’s a ten-

11

Joey collects his $5,000 prize money, poses for the cameras, and disappears behind the stage, where I find him looking terrible. . . .

12

Competitive eating is, of course, a manifestation of the American urge to turn absolutely everything, even something as elemental as eating, into a competition. And it is as old as America itself—

73

13

Joey “Jaws” Chestnut grew up in Vallejo, California. Being the third of four boys, he was always searching for something he could beat his older brothers at. And that thing seemed to be eating very fast. He showed such a talent for it that in 2005, his youngest brother entered him into a lobster competition in Reno. “I’d never eaten lobster before,” Joey told me. “I was 21. I didn’t know what the heck I was doing. I was scooping guts. But I tied for third. And the two men who beat me didn’t look good. One was Bob Shoudt. He seemed in pain. And I felt fine! I was ‘Oh, my God, they look like they’re dying. And I can eat so much more!’ I knew I was made for it after that contest.”

14

Joey decided that night to dedicate his life to the pursuit. He became obsessed—

15

And now the big one. Coney Island. The Fourth of July. The Nathan’s Famous International Hot Dog Eating Championship, with a $10,000 first prize. “The only one,” Pat Bertoletti tells me, “the public really cares about.”

16

Thousands have gathered on the boardwalk by the beach. Many are chanting “U.S.A.! U.S.A.!” Onto the giant stage marches a procession of stilt walkers, dwarves dressed as Uncle Sam, cheerleaders, bodybuilders, a girl singing “The Star-

17

The eaters are crowded into a little room backstage where thousands of hot dogs are being mass-

18

“You’ve seen everything I do,” Joey replied. I turned to Pat. “Do you sometimes feel like Buzz Aldrin to Joey’s Neil Armstrong?”

19

“For sure,” he said. Despite the tough-

20

“I don’t think I can ever win [hot dogs],” he told Joey and me. “And I’ve done everything else.” “You might quit everything?” I asked. “Yeah,” said Pat. Then Joey said, “I’ve thought about getting out, too.”

21

“You want out, too?” said Pat, incredulous.

22

“I do,” said Joey.

23

“Why?” I asked him.

24

He backpedaled slightly. “It’s not that I want out,” he said, “but I don’t want to linger.”

25

What he meant is that once you’re number one, there’s nowhere to go. Joey is trapped at number one like Pat is trapped at number two.

74

26

“My goal is seven [Nathan’s titles] in a row,” Joey said. “Next year could very well be my last.”

27

“Do you also want to quit because you realize it’s a bizarre way to live your life?” I asked him.

28

“Probably,” Joey said.

29

The truth is, rarely have I done a story about something that’s so utterly, existentially pointless and so emblematic of the American tendency to go way too far. . . .

30

Halfway through the contest, something impossible seems to be happening. “Matt Stonie!” George Shea is yelling into the microphone. “Many are calling him the new Joey Chestnut! This is amazing, ladies and gentlemen! Matt Stonie is doing so well he’s only four hot dogs behind Joey Chestnut. Nineteen years of age! And yet he’s the only one truly putting pressure on Joey Chestnut!” . . . He’s gaining on Joey, all those years of pain propelling him on. Twenty-

31

The audience—

[REFLECT]

Make connections: Competitive eating as a sport.

Notice that Ronson, who was born and bred in Wales, in the United Kingdom, talks about competitive eating as a typically American “sport” (par. 12). Consider Ronson’s take on American values and attitudes toward sports in relation to your own views. Your instructor may ask you to post your thoughts on a class discussion board or to discuss them with other students in class. Use these questions to get started:

How accurate are Ronson’s two assertions: that the sport is “a manifestation of the American urge to turn absolutely everything, even something as elemental as eating, into a competition” (par. 12) and that it is “emblematic of the American tendency to go way too far” (par. 29)?

How is competitive eating like and unlike other sports that you consider typically American?

How does Ronson use the genre of the profile to portray competitive eating as a sport? Where in the profile, for example, do you see the kinds of discourse (such as play-

by- play narration and up- close- and- personal interview) you associate with sports reporting?

[ANALYZE]

Use the basic features.

SPECIFIC INFORMATION ABOUT THE SUBJECT: DESCRIBING PEOPLE THROUGH NAMING, DETAILING, AND COMPARING

Profiles, like remembered events (Chapter 2), succeed in large part by presenting the people being observed and interviewed. Using the describing strategies of naming, detailing, and comparing, Ronson gives readers a series of graphic images showing us some of the main figures competing with Joey Chestnut, the focus of Ronson’s profile.

(To learn more about these describing strategies, see Chapter 15.)

75

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a paragraph analyzing Ronson’s use of describing strategies in The Hunger Games to give readers a vivid impression of a person:

Look closely at Ronson’s thumbnail portraits of Pat Bertoletti, Maria Edible, Bob Shouldt, and Matt Stonie (par. 4).

Choose one portrait that gives you a strong impression, and briefly explain what you think makes that portrait work so well. You might focus, for example, on a specific detail of the person’s appearance or a striking comparison (metaphor or simile) that captures something important about the individual’s personality.

A CLEAR, LOGICAL ORGANIZATION: USING FLASHBACKS

Profiles organized narratively usually follow a fairly straightforward chronology from past to present. Occasionally, however, they may diverge from this conventional way of storytelling to recount something that occurred in the past, using flashbacks. In profiles, flashbacks can be used to interject historical information, a memory, or reflection into the ongoing narrative (as in the following example from Cable’s essay). To avoid confusing readers, flashbacks are usually marked by time cues and verb tenses to indicate different points in time:

Ongoing past

Present

Simple Past

Howard has been in this business for forty years. He remembers a time when everyone was buried. (Cable, par. 22)

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a paragraph analyzing Ronson’s use of flashbacks in The Hunger Games:

Skim the profile looking for flashbacks, highlighting the cues Ronson uses to signal time shifts.

Consider why Ronson uses flashbacks and how else he could have incorporated the information he presents in this way.

THE WRITER’S ROLE: ACTING AS A SPECTATOR

Like Cable, Ronson assumes the role of a spectator. He places himself in the scene as a sort of eyewitness, using the first-

Here are some typical sentence strategies illustrating the spectator role:

I expected/anticipated/felt/observed........... .

I asked/pondered/wondered ......... ?

76

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a paragraph analyzing Ronson’s role in The Hunger Games:

Reread Ronson’s profile marking passages where he places himself in the scene. Note whether he uses the first-

person pronoun “I” to cue readers or signals in some other way that he is making observations, expressing expectations, or interviewing people. Consider how this profile would be different if Ronson had adopted the role of a participant-

observer instead of a spectator. What new insights might he have gotten from participating in an eating contest, for example?

A PERSPECTIVE ON THE SUBJECT: SHOWING AND TELLING

All of the profiles in this chapter use a combination of showing and telling to convey the writer’s perspective on or ideas about the subject. Cable shows his anxiety about death, for example, by describing his hesitation to get close to and touch a dead body (pars. 15, 28). He uses comparisons to give readers a dominant impression of the funeral home as all business:

His tone was that of a broker conferring on the Dow Jones. (par. 9)

Inside were thirty coffins, lids open, patiently awaiting inspection. Like new cars on the showroom floor. . . .

In addition, Cable tells readers directly about what he observed, for instance, in the opening paragraphs and in his questioning of Tim about whether burials play “an important role in society” (par. 22).

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a couple of paragraphs analyzing Ronson’s use of showing and telling to convey his perspective in The Hunger Games:

Focus first on Ronson’s depiction of Joey. Briefly explain the dominant impression you get from the description and dialogue, quoting a few examples to illustrate your explanation.

Next, select a couple of examples where Ronson tells readers what he thinks about the sport and about Joey.

Finally, consider how the showing and telling work together to create a dominant impression of Joey Chestnut.

[RESPOND]

Consider possible topics: Profiling a sport or a sports figure.

Consider profiling a sport. You could focus on an offbeat sport (curling, extreme skateboarding), follow a team at your high school or college, perhaps focusing on a particular player or coach, or focus on a local children’s sports team or karate dojo. If you are interested in health care professions, you might observe and write about a sports injury clinic in your community. To learn about the business side of college sports, consider interviewing the director or business manager of your college athletics association.