Improving the Draft: Revising, Editing, and Proofreading

Start improving your draft by reflecting on what you have written thus far:

Review critical reading comments from your classmates, instructor, or writing center tutor. What are your readers getting at?

Take another look at the notes from your earlier research and writing activities. What else should you consider?

Review your draft. What else can you do to make your explanation effective?

Revise your draft.

If your readers are having difficulty with your draft, or if you think there is room for improvement, try some of the strategies listed in this Troubleshooting Guide. It can help you fine-

A TROUBLESHOOTING GUIDE

Click the Troubleshooting Guide to download.

| A Focused Explanation |

My readers think that my topic seems thin, that I don’t have enough to write about. (The focus is too narrow.)

163 My readers don’t find my focus interesting.

|

| A Clear, Logical Organization |

My readers don’t find my organization clear and logical.

My readers say that the beginning doesn’t capture their interest.

My readers feel that the essay doesn’t flow smoothly from one part to the next.

My readers feel that the ending falls flat.

|

164

| Appropriate Explanatory Strategies |

My readers don’t understand my explanation.

My readers want more information about certain aspects of the concept.

My readers think visuals would help them better understand the concept.

My readers think my summaries are vague, paraphrases are too complicated, or quotations are too long or uninteresting.

My readers aren’t sure how source information supports my explanation of the concept.

|

165

| Smooth Integration of Sources |

My readers think that the quotations, summaries, and paraphrases don’t flow smoothly with the rest of the essay.

My readers are concerned that my list of sources is too limited.

My readers wonder whether my sources are credible.

|

Edit and proofread your draft.

A Note on Grammar and Spelling Checkers

These tools can be helpful, but don’t rely on them exclusively to catch errors in your text: Spelling checkers cannot catch misspellings that are themselves words, such as to or too. Grammar checkers miss some problems, sometimes give faulty advice for fixing problems, and can flag correct items as wrong. Use these tools as a second line of defense after your own (and, ideally, another reader’s) proofreading and editing efforts.

Two kinds of errors occur often in concept explanations: mixed constructions and missing or unnecessary commas around adjective clauses. The following guidelines will help you check your essay for these common errors.

Avoiding Mixed Constructions

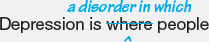

What Is a Mixed Construction? A mixed construction in a sentence is a combination of structures that don’t work together properly according to the rules of logic or English grammar. Mixed constructions often occur when a writer attributes information to a source, defines a term, or provides an explanation. In particular, watch out for definitions that include is when or is where and explanations that include the reason. . . is because, which are likely to be both illogical and ungrammatical.

The Problem Sentences are logically or grammatically incoherent.

The Correction Replace when or where with a noun that renames the subject or with an adjective that describes the subject.

feel sad, guilty, or worthless, and lack energy or focus.

feel sad, guilty, or worthless, and lack energy or focus.

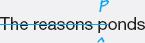

Delete either the reason . . . is or because.

166

become meadows

become meadows  because plant life collects in the bottom.

because plant life collects in the bottom.

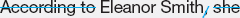

Check subjects and predicates to make sure they are logically and grammatically matched, and delete any redundant expressions.

said that the best movie of the year was Fury Road.

said that the best movie of the year was Fury Road.According to Eleanor Smith,

the best movie of the year was Fury Road.

the best movie of the year was Fury Road.

Using Punctuation with Adjective Clauses

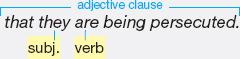

What Is an Adjective Clause? An adjective clause includes both a subject and a verb, gives information about a noun or a pronoun, and often begins with who,which, or that:

It is common for schizophrenics to have delusions

Because adjective clauses add information about the nouns they follow — defining, illustrating, or explaining — they can be useful in writing that explains a concept.

The Problem Adjective clauses may or may not need to be set off with a comma or commas. To decide, determine whether the clause is essential to the meaning of the sentence. Essential clauses should not be set off with commas; nonessential clauses must be set off with commas.

The Correction Mentally delete the clause. If taking out the clause does not change the basic meaning of the sentence or make it unclear, add a comma or commas.

Postpartum

can last for two weeks or

can last for two weeks or  adversely affect a mother’s ability to care for her infant.

adversely affect a mother’s ability to care for her infant.

If the clause follows a proper noun, add a comma or commas.

Nanotechnologists defer to K. Eric

speculates imaginatively about the use of nonmachines.

speculates imaginatively about the use of nonmachines.

If taking out the clause changes the basic meaning of the sentence or makes it unclear, do not add a comma or commas.

Seasonal affective disorders are mood

occur in fall/winter.

occur in fall/winter.