Ice as a Rock

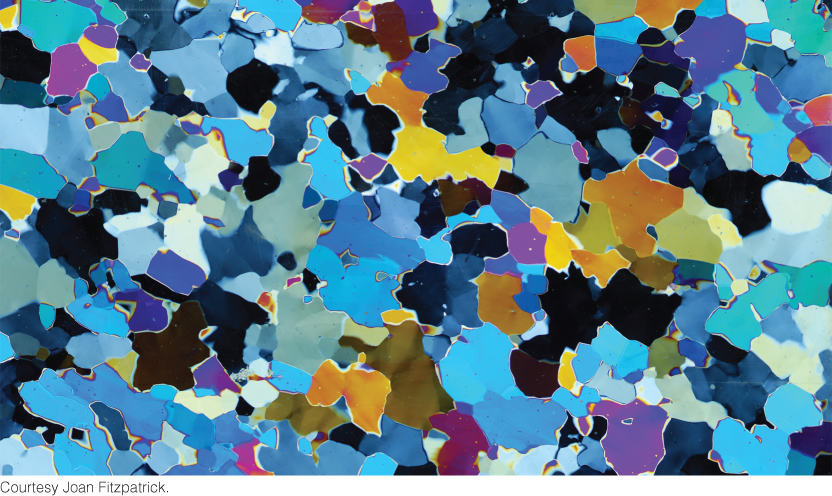

To a geologist, a block of ice is a rock, a mass of crystalline grains of the mineral ice. Like igneous rock, it is formed by the freezing of a fluid. Like sedimentary rock, it is formed from materials deposited in layers at Earth’s surface and can accumulate to great thicknesses. Like metamorphic rock, it is transformed by recrystallization under pressure; that is, glacial ice is formed by the burial and metamorphism of the “sediment” snow. Loosely packed snowflakes—each a single crystal of the mineral ice—age and recrystallize into a solid rock of ice (Figure 21.1).

Ice has some unusual properties. Its melting temperature is very low (0°C), hundreds of degrees below the melting temperatures of silicate rock. Most rocks are denser than their melts, which is why magma rises buoyantly through the lithosphere. But ice is less dense than its melt, which is why icebergs float on the ocean. And although ice may seem hard, it is much weaker than most rocks.

Because ice is so weak, it flows readily downhill like a viscous fluid. Glaciers are large masses of ice on land that show evidence of being in motion, or of once having moved, under the force of gravity. We divide glaciers, on the basis of their size and shape, into two basic types: valley glaciers and continental glaciers.

Valley Glaciers

Many skiers and mountain climbers are familiar with valley glaciers, sometimes called alpine glaciers (Figure 21.2). These rivers of ice form in the cold heights of mountain ranges, where snow accumulates. They then move downslope, either flowing down an existing stream valley or carving out a new one. A valley glacier usually occupies the complete width of the valley and may bury its floor under hundreds of meters of ice. In warmer, low-latitude climates, valley glaciers are found only at the heads of valleys on the highest mountain peaks. An example is the glacial ice that covers the Mountains of the Moon at elevations over 5000 m along the Uganda-Zaire border in east-central Africa. In colder, high--latitude climates, valley glaciers may descend many kilometers, down the entire length of a valley. Broad lobes of ice may descend into lower lands bordering mountain fronts. Valley glaciers that flow down coastal mountain ranges at high latitudes may terminate at the ocean’s edge, where masses of ice break off and form icebergs—a process called iceberg calving (Figure 21.3).

589

590

Continental Glaciers

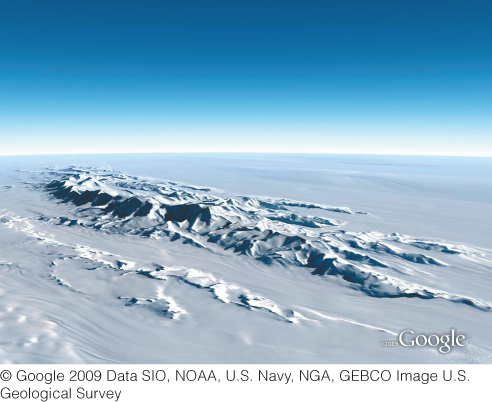

A continental glacier is a thick, slow-moving sheet of ice (sometimes called an ice sheet) that covers a large part of a continent or other large landmass (Figure 21.4). Today, the world’s largest continental glaciers overlie much of Greenland and Antarctica, covering about 10 percent of Earth’s land surface and storing about 75 percent of the world’s fresh water.

In Greenland, 2.6 million cubic kilometers of ice occupy 80 percent of the island’s total area of 4.5 million square kilometers (Figure 21.5). The upper surface of the ice sheet resembles an extremely wide convex lens. At its highest point, in the middle of the island, the ice is more than 3200 m thick. From this central area, the ice surface slopes to the ocean on all sides. At the mountain-rimmed coast, the ice sheet breaks up into narrow tongues resembling valley glaciers that wind through the mountains to reach the ocean, where icebergs form by calving.

The bowl shape of the bedrock beneath the Greenland ice sheet, evident in the cross section at the bottom of Figure 21.5, is caused by the weight of the ice in the middle of the island. This consequence of isostasy explains why mountains rim the Greenland coast.

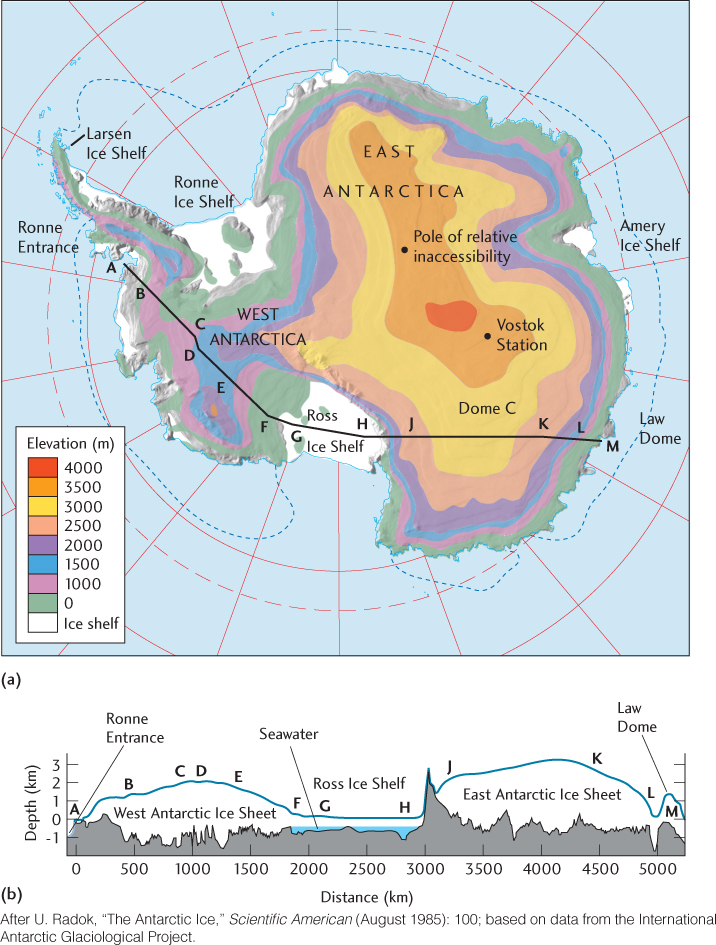

Though very large, the Greenland glacier is dwarfed by the Antarctic ice sheet. Ice blankets 90 percent of Antarctica, covering an area of about 13.6 million square kilometers and reaching thicknesses of 4000 m (Figure 21.6). The total volume of Antarctic ice—about 30 million cubic kilometers—constitutes over 90 percent of the cryosphere. As in Greenland, the ice forms a dome in the center and slopes down to the margins of the continent.

Parts of Antarctica are rimmed by thinner sheets of ice—ice shelves—floating on the ocean and attached to the main glacier on land. The best known of these is the Ross Ice Shelf, a thick layer of ice about the size of Texas that floats on the Ross Sea.

Ice caps are the masses of ice that blanket Earth’s North and South Poles. Most of the Arctic ice cap, located at the highest latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere, lies over water and is not a glacier. Almost all of the Antarctic ice cap lies on the continent of Antarctica and is therefore a continental glacier.

591