Topography, Elevation, and Relief

The term geomorphology refers both to the shape of a landscape and to the branch of Earth science concerned with that shape and how it develops. We begin our study of geomorphology here with the elementary observations of any landscape that are obvious as one examines Earth’s surface: the height and ruggedness, or roughness, of mountains and lowlands.

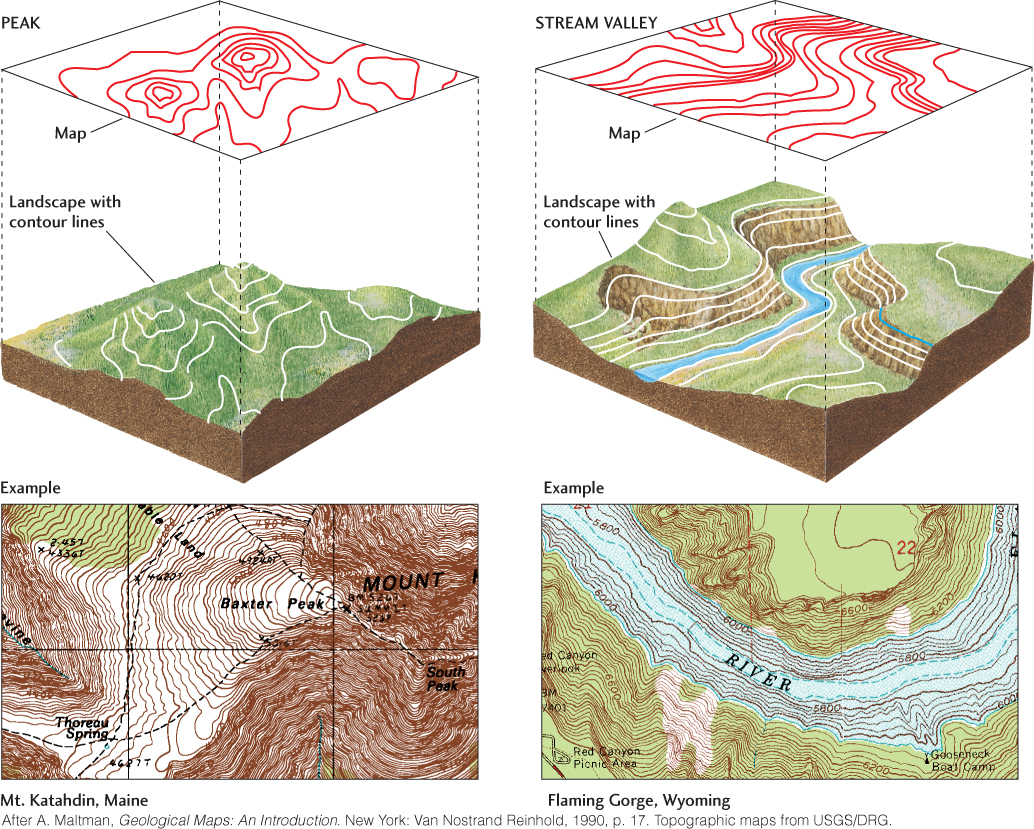

Topography is the general configuration of varying heights that gives shape to Earth’s surface (see Figure 1.8). We compare the heights of landscape features with sea level: the average height of the ocean surface throughout the world. We then express the vertical distance above or below sea level as elevation. A topographic map shows the distribution of elevations in an area. This distribution is most often represented by contours, lines that connect points of equal elevation (Figure 22.1). The more closely spaced the contours, the steeper the slope.

619

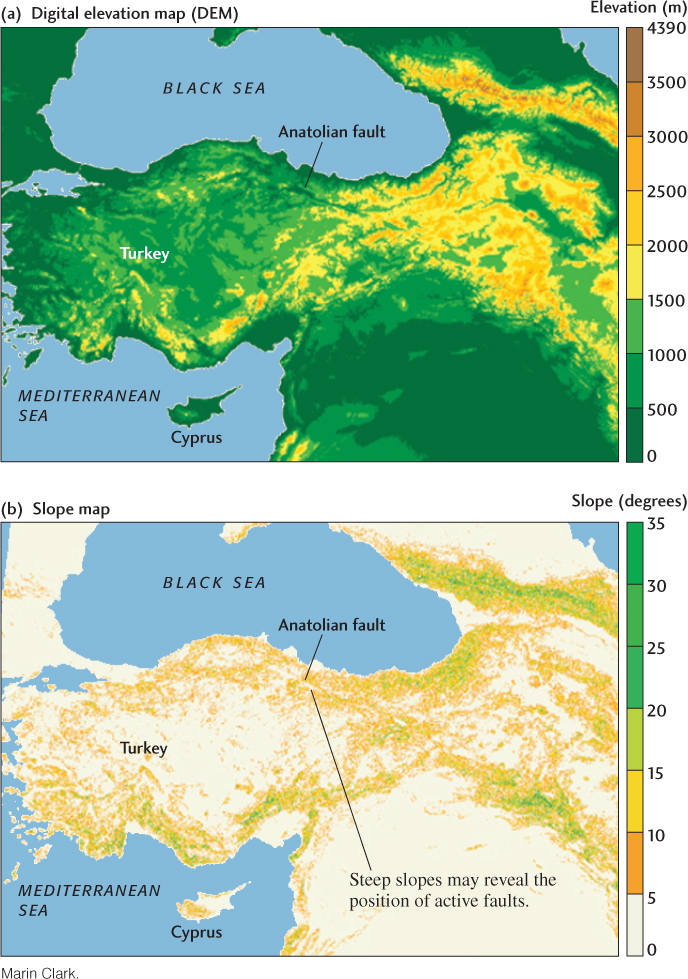

Centuries ago, geologists learned to survey topography and construct maps to plot and record geologic information. Although land surveying based on age-old methods is still used for some purposes, modern mapmakers rely on satellite photographs, radar imaging, airborne laser range finders, and other technologies that enable them to discern elevation and other topographic properties (Figure 22.2).

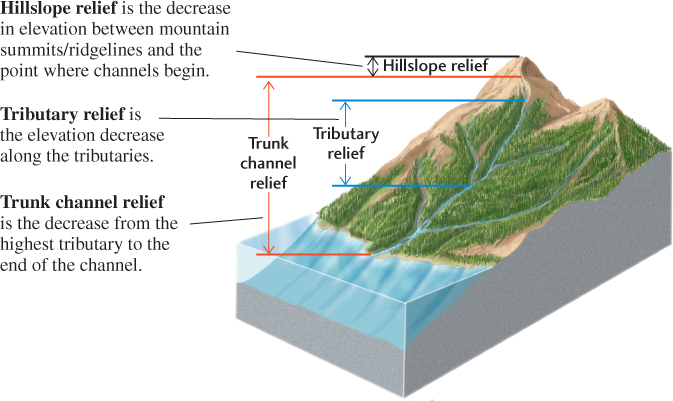

One of the properties of topography is relief: the difference between the highest and lowest elevations in a particular area (Figure 22.3). As this definition implies, relief varies with the scale of the area over which it is measured. In studies of geomorphology, it is useful to define three fundamental components of relief: hillslope relief (the decrease in elevation between mountain summits or ridgelines and the point at which stream channels begin), tributary relief (the decrease in elevation along tributary stream channels from their beginning to the main, or trunk, stream with which they merge), and trunk channel relief (the decrease in elevation from the highest tributary to the end of the trunk stream channel).

620

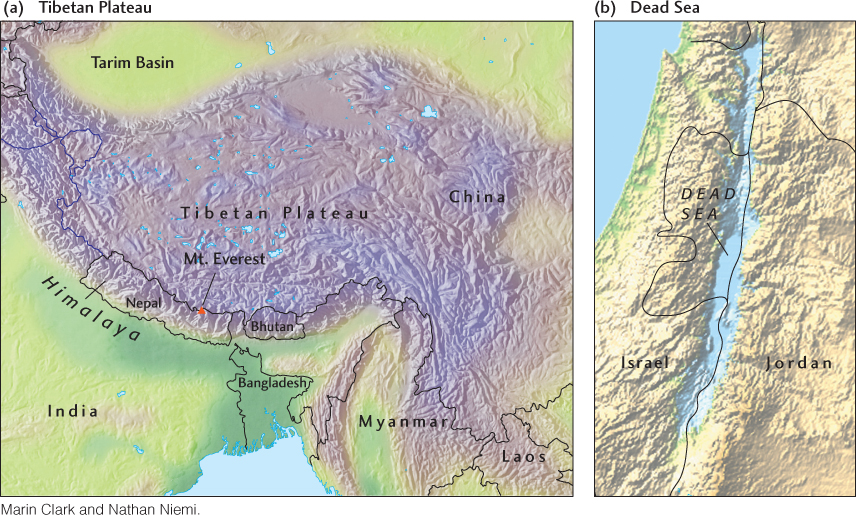

To estimate relief in an area of interest from contours on a topographic map, we subtract the elevation of the lowest contour, usually at the bottom of a stream valley, from that of the highest contour at the top of the highest hill or mountain. Relief is a measure of the roughness of a terrain: the greater the relief, the more rugged the topography. Mount Everest in the Himalaya—the highest mountain in the world, with an elevation of 8850 m—is located in an area of extremely high relief (Figure 22.4a). In general, most regions of high elevation are also areas of high relief, and most areas of low elevation are areas of low relief. There are exceptions, however. For example, the Dead Sea, between Israel and Jordan, has the lowest land elevation in the world at 392 m below sea level, but it is flanked by impressive mountains that provide significant relief in this small region (Figure 22.4b). Other regions, such as the Tibetan Plateau, lie at high elevations but have relatively low relief (see Figure 22.4a).

If we fly over North America, we can see many kinds of topography. Figure 22.5 is a computer-processed digital relief map that shows the details of large- and small-scale landforms. This digital map provides an overall view of the continent while showing features as small as 2.5 km across. The moderate elevations and relief of the elongate ridges and valleys of the Appalachian Mountains contrast with the low elevations and relief of the midwestern plains. Even more striking is the contrast between the plains and the Rocky Mountains. As we examine these different types of topography more closely, we can characterize them not only by elevation and relief, but also by their landforms: the steepness of their slopes, the shapes of their mountains or hills, and the forms of their valleys.

621