Sedimentary Structures

Sedimentary structures include all kinds of features formed at the time of deposition. Sediments and sedimentary rocks are characterized by bedding, or stratification, which occurs when layers of sediment, or beds, with different particle sizes or compositions are deposited on top of one another. These beds range from only millimeters or centimeters thick to meters or even many meters thick. Most bedding is horizontal, or nearly so, at the time of deposition. Some types of bedding, however, form at a high angle relative to the horizontal.

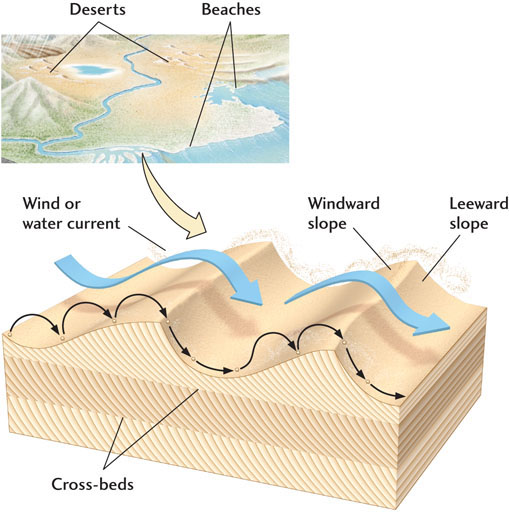

Cross-Bedding

Cross-bedding consists of beds deposited by wind or water and inclined at angles as much as 35° from the horizontal (Figure 5.11). Cross-beds form when sediment particles are deposited on the steeper, downcurrent (leeward) slopes of sand dunes on land or sandbars in rivers and on the seafloor. Cross-bedding patterns in wind-deposited sand dunes may be complex as a result of rapidly changing wind directions (as in the photograph at the opening of this chapter). Cross-bedding is common in sandstones and is also found in gravels and some carbonate sediments. It is easier to see in sandstones than in sands, which must be excavated to see a cross section.

Graded Bedding

Graded bedding is most abundant in continental slope and deep-sea sediments deposited by dense, muddy turbidity currents, which hug the bottom of the ocean as they move downhill. Each bed progresses from large particles at the bottom to small particles at the top. As the current progressively slows, it drops progressively smaller particles. The grading indicates a weakening of the current that deposited the particles. A graded bed comprises one set of sediment particles, normally ranging from a few centimeters to several meters thick, that formed a horizontal or nearly horizontal layer at the time of deposition. Accumulations of many individual graded beds can reach a total thickness of hundreds of meters. A graded bed formed as a result of deposition by a turbidity current is called a turbidite.

128

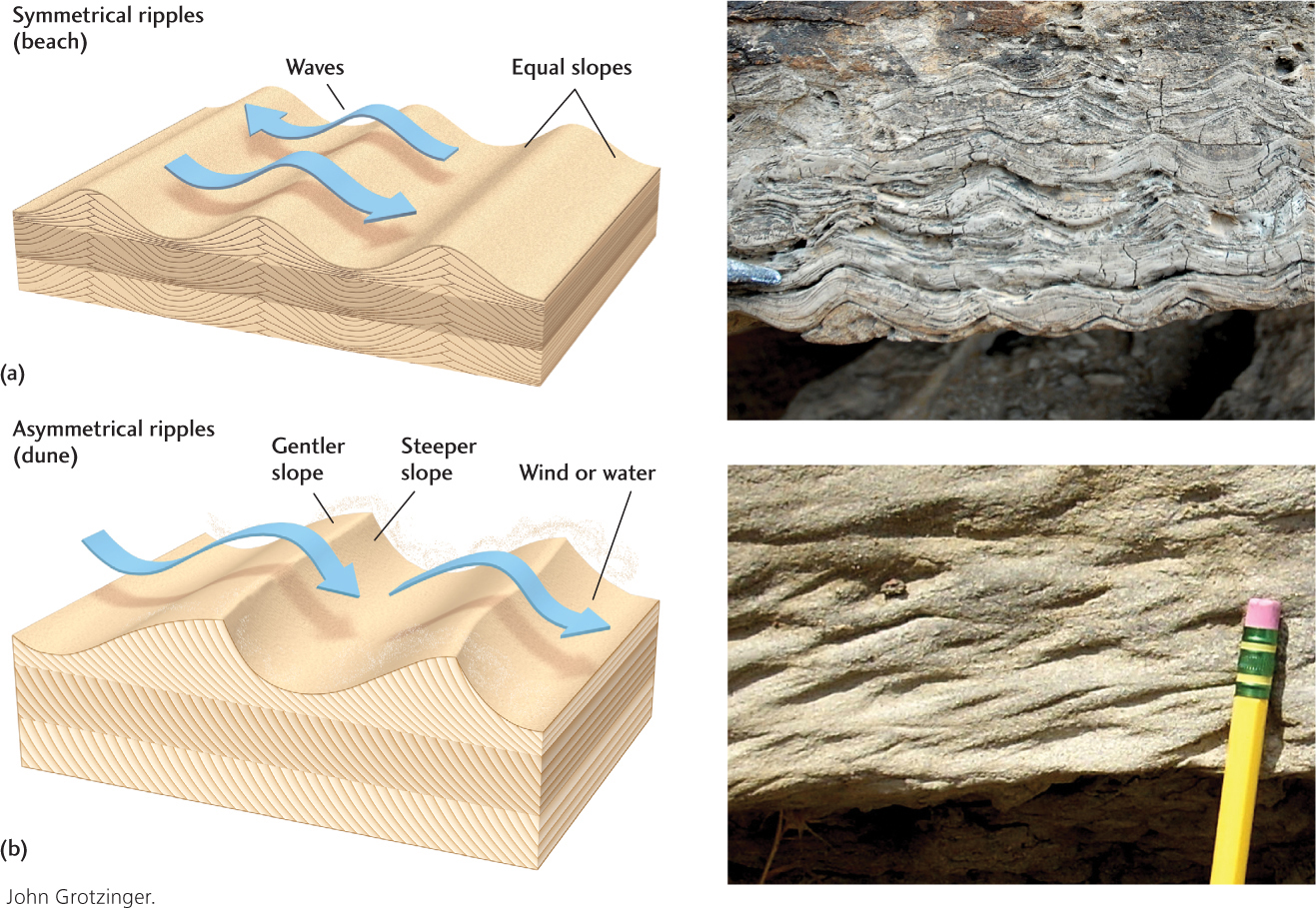

Ripples

Ripples are very small ridges of sand or silt whose long dimension is at right angles to the current. They form low, narrow ridges, usually only a centimeter or two high, separated by wider troughs. These sedimentary structures are common in both modern sands and ancient sandstones (Figure 5.12). Ripples can be seen on the surfaces of windswept dunes, on underwater sandbars in shallow streams, and under the waves at beaches. Geologists can distinguish the symmetrical ripples made by waves moving back and forth on a beach from the asymmetrical ripples formed by currents moving in a single direction over river sandbars or windswept dunes (Figure 5.13).

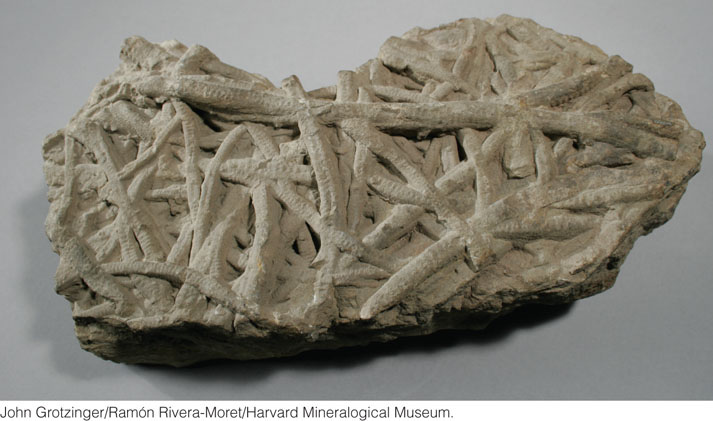

Bioturbation Structures

In many sedimentary rocks, the bedding is broken or disrupted by roughly cylindrical tubes a few centimeters in diameter that extend vertically through several beds. These sedimentary structures are remnants of burrows and tunnels excavated by clams, worms, and other marine organisms that live on the ocean bottom. These organisms churn and burrow through muds and sands—a process called bioturbation. They ingest the sediment, digest the bits of organic matter it contains, and leave behind the reworked sediment, which fills the burrow (Figure 5.14). From bioturbation structures, geologists can determine the behavior of the organisms that burrowed in the sediment. Since the behavior of burrowing organisms is controlled partly by environmental factors, such as the strength of currents or the availability of nutrients, bioturbation structures can help us reconstruct past sedimentary environments.

129

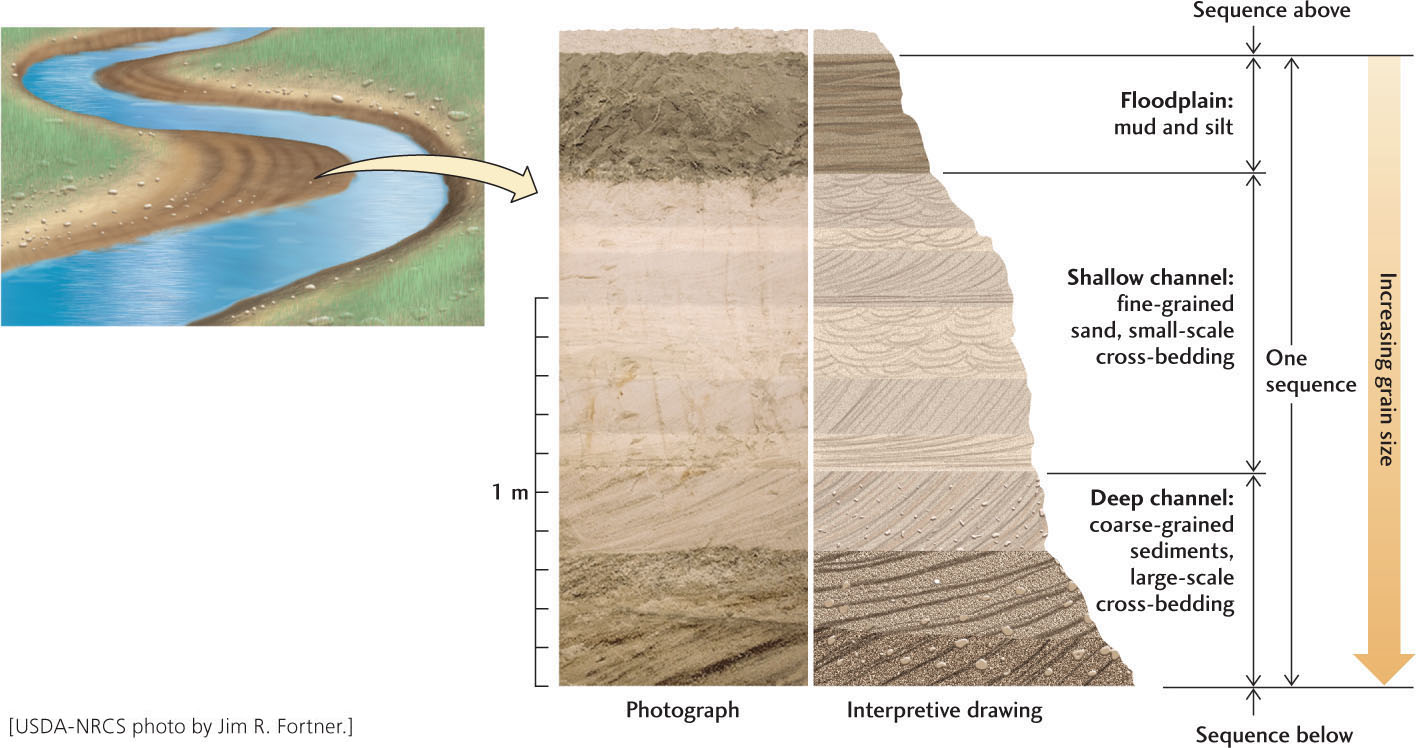

Bedding Sequences

Bedding sequences are built of interbedded and vertically stacked layers of different sedimentary rock types. A bedding sequence might consist of cross-bedded sandstone, overlain by bioturbated siltstone, overlain in turn by rippled sandstone—in any combination of thicknesses for each rock type in the sequence.

Bedding sequences help geologists reconstruct the ways in which sediments were deposited and so provide insight into the history of geologic processes and events that occurred at Earth’s surface long ago. Figure 5.15 shows a bedding sequence typically formed in alluvial sedimentary environments. A river lays down sediments as its channel meanders back and forth across the valley floor. Thus, the lower part of the sequence contains the beds deposited in the deepest part of the river channel, where the current was strongest. The middle part contains the beds deposited in the shallower parts of the channel, where the current was weaker, and the upper part contains the beds deposited on the floodplain. Typically, a bedding sequence formed in this manner consists of sediment particles that grade upward from large to small. This sequence may be repeated a number of times if the river meanders back and forth.

130

Most bedding sequences consist of a number of small-scale subdivisions. In the example shown in Figure 5.15, the basal layers contain cross-bedding. These layers are overlain by more cross-bedded layers, but the cross-beds are smaller in scale. Horizontal bedding occurs at the top of the bedding sequence. Today, computer models are used to analyze how bedding sequences of sands were deposited in alluvial environments.