How Rocks Deform

Rocks deform in response to the tectonic forces acting on them. Whether they will respond to tectonic forces by folding, faulting, or some combination of the two depends on the orientation of the forces, the rock type, and the physical conditions (such as temperature and pressure) during deformation.

Brittle and Ductile Behavior of Rocks in the Laboratory

In the mid-1900s, geologists began to explore the forces of deformation by using powerful hydraulic rams to bend and break small samples of rock. Engineers had invented such machines to measure the strength of concrete and other building materials, but geologists modified them to discover how rocks deform at pressures and temperatures high enough to simulate physical conditions deep in Earth’s crust.

176

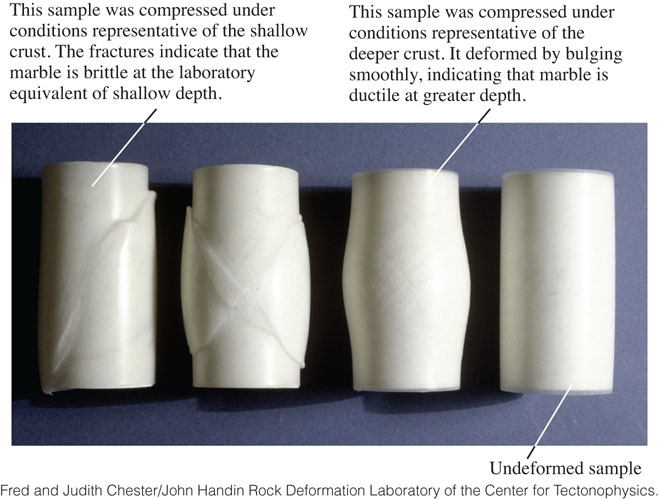

In one such experiment, the researchers applied compressive force by pushing down with a hydraulic ram on one end of a small cylinder of marble while at the same time maintaining confining pressure on the cylinder (Figure 7.6). Under low confining pressures, equivalent to those found at shallow depths in Earth’s crust, the marble sample deformed only a small amount until the compressive force on its end was increased to the point that the entire sample suddenly broke (see Figure 7.6, left side). This experiment showed that marble behaves as a brittle material at the low confining pressures found in the shallow crust. Repeating the experiment under high confining pressures, equivalent to those that often accompany metamorphism, produced a different result: the marble sample slowly and steadily deformed into a shortened, bulging shape without fracturing (see Figure 7.6, right side). Marble thus behaves as a pliable, or ductile, material at the high confining pressures found deep in the crust.

Other experiments showed that when marble was heated to temperatures as high as those that accompany metamorphism, it acted as a ductile material at a lower confining pressure—just as heating wax changes it from a hard material that can break into a soft material that flows. The researchers concluded that the particular marble they were working with would deform by faulting at depths shallower than a few kilometers, but would deform by folding at the greater crustal depths where metamorphism generally occurs.

Brittle and Ductile Behavior of Rocks in Earth’s Crust

Natural conditions in Earth’s crust cannot be reproduced exactly in the laboratory. Tectonic forces are applied over millions of years, whereas laboratory experiments are rarely conducted over more than a few hours, or at most a few weeks. Nevertheless, the results of laboratory experiments can help us interpret what we see in the field. Geologists keep the following points in mind when mapping crustal folds and faults:

The same rock can be brittle at shallow depths (where temperatures and pressures are relatively low) and ductile deep in the crust (where temperatures and pressures are higher). Metamorphism is usually accompanied by ductile deformation.

The same rock can be brittle at shallow depths (where temperatures and pressures are relatively low) and ductile deep in the crust (where temperatures and pressures are higher). Metamorphism is usually accompanied by ductile deformation. Rock type affects deformation. In particular, the hard igneous and metamorphic rocks that form the crystalline basement of a continent (the crust beneath layers of sediments) often behave as brittle materials, fracturing along faults during deformation, while softer sedimentary rocks that overlie them often behave as ductile materials, folding gradually.

Rock type affects deformation. In particular, the hard igneous and metamorphic rocks that form the crystalline basement of a continent (the crust beneath layers of sediments) often behave as brittle materials, fracturing along faults during deformation, while softer sedimentary rocks that overlie them often behave as ductile materials, folding gradually. A rock formation that would behave as a ductile material if deformed slowly may behave as a brittle material if deformed more rapidly. (Think of Silly Putty, which flows as a ductile clay when you squeeze it slowly, but breaks into pieces when you pull it apart very quickly.)

A rock formation that would behave as a ductile material if deformed slowly may behave as a brittle material if deformed more rapidly. (Think of Silly Putty, which flows as a ductile clay when you squeeze it slowly, but breaks into pieces when you pull it apart very quickly.) Rocks break more easily when subjected to tensional (pulling and stretching) forces than when subjected to compressive forces. Sedimentary rock formations that will deform by folding during compression will often break along faults when subjected to tension.

Rocks break more easily when subjected to tensional (pulling and stretching) forces than when subjected to compressive forces. Sedimentary rock formations that will deform by folding during compression will often break along faults when subjected to tension.

177