12-8 Earth-based observations reveal three broad rings encircling Saturn

Compared to Saturn, Jupiter is unquestionably larger, more massive, more colorful, and more dynamic in both its atmosphere and magnetosphere. But as seen through even a small telescope, Saturn stands out as perhaps the most beautiful of all the worlds of the solar system, thanks to its majestic rings (Figure 12-16). As we will see in Section 12-9, Jupiter also has rings, but they are so faint that they were not discovered until spacecraft could observe Jupiter at close range.

Compared to Saturn, Jupiter is unquestionably larger, more massive, more colorful, and more dynamic in both its atmosphere and magnetosphere. But as seen through even a small telescope, Saturn stands out as perhaps the most beautiful of all the worlds of the solar system, thanks to its majestic rings (Figure 12-16). As we will see in Section 12-9, Jupiter also has rings, but they are so faint that they were not discovered until spacecraft could observe Jupiter at close range.

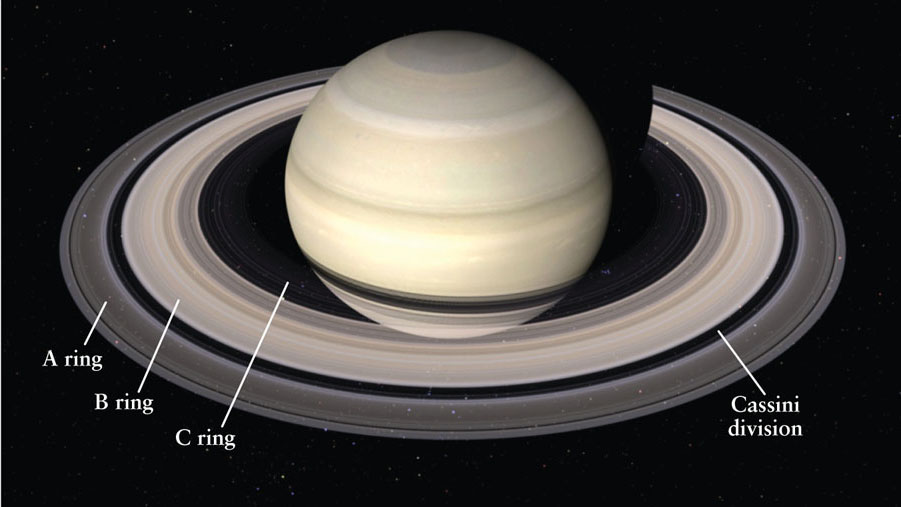

Saturn’s System of Rings This Cassini image shows many details of Saturn’s rings. The C ring is so faint that it is almost invisible in this view. At 274,000 km, the outer diameter of the A ring is almost twice the diameter of Jupiter. Saturn is visible through the rings (look near the very bottom of the image), which shows that the rings are not solid. The ring system is so large that Mercury could fit inside the Cassini division.

Discovering Saturn’s Rings

In 1610, Galileo became the first person to see Saturn through a telescope. He saw few details, but he did notice two puzzling lumps protruding from opposite edges of the planet’s disk. Curiously, these lumps disappeared in 1612, only to reappear in 1613. Other observers saw similar appearances and disappearances over the next several decades.

In 1655, the Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens began to observe Saturn with a better telescope than was available to any of his predecessors. (We discussed in Section 11-2 how Huygens used this same telescope to observe Mars.) On the basis of his observations, Huygens suggested that Saturn was surrounded by a thin, flattened ring. At times this ring was edge-on as viewed from Earth, making it almost impossible to see. At other times Earth observers viewed Saturn from an angle either above or below the plane of the ring, and the ring was visible, as in Figure 12-1. (The lumps that Galileo saw were the parts of the ring to either side of Saturn, blurred by the poor resolution of his rather small telescope.) Astronomers confirmed this brilliant deduction over the next several years as they watched the ring’s appearance change just as Huygens had predicted.

As the quality of telescopes improved, astronomers realized that Saturn’s “ring” is actually a system of rings, as Figure 12-16 shows. In 1675, the Italian astronomer Cassini discovered a dark division in the ring. The Cassini division is a gap about 4800 kilometers wide that separates the outer A ring from the brighter B ring closer to the planet. In the mid-1800s, astronomers managed to identify the faint C ring, or crepe ring, that lies just inside the B ring. To appreciate the enormous scale of the ring system, consider that Mercury could fit snugly within the Cassini division!

Saturn and its rings are best seen when the planet is at or near opposition. A modest telescope gives a good view of the A and B rings, but a large telescope and excellent observing conditions are needed to see the C ring.

How the Rings Appear from Earth

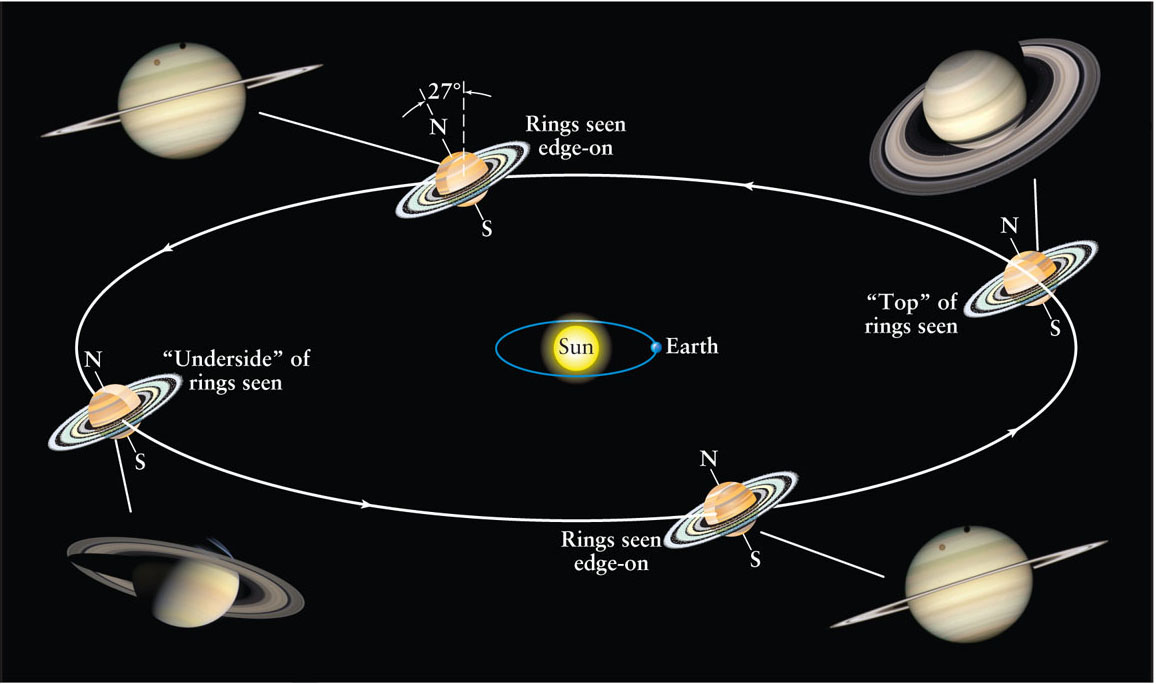

Earth-based views of the Saturnian ring system change as Saturn slowly orbits the Sun. Huygens was the first to understand that this change occurs because the rings lie in the plane of Saturn’s equator, and this plane is tilted 27° from the plane of Saturn’s orbit. As Saturn orbits the Sun, its rotation axis and the plane of its equator maintain the same orientation in space. (The same is true for Earth; see Figure 2-12.) Hence, over the course of a Saturnian year, an Earth-based observer views the rings from various angles (Figure 12-17). At certain times Saturn’s north pole is tilted toward Earth and the observer looks “down” on the “top side” of the rings. Half a Saturnian year later, Saturn’s south pole is tilted toward us and the “underside” of the rings is exposed to our Earth-based view.

The Changing Appearance of Saturn’s Rings Saturn’s rings are aligned with its equator, which is tilted 27° from Saturn’s orbital plane. As Saturn moves around its orbit, the rings maintain the same orientation in space, so observers on Earth see the rings at various angles. The accompanying images of Saturn are made from the “underside” of the rings, the “top” side, and nearly edge-on.

The Changing Appearance of Saturn’s Rings Saturn’s rings are aligned with its equator, which is tilted 27° from Saturn’s orbital plane. As Saturn moves around its orbit, the rings maintain the same orientation in space, so observers on Earth see the rings at various angles. The accompanying images of Saturn are made from the “underside” of the rings, the “top” side, and nearly edge-on.

As seen from Earth, Saturn’s rings change their orientation as the planet orbits the Sun

When our line of sight to Saturn is in the plane of the rings, the rings are viewed edge-on and seem to disappear entirely (see the images at the upper left and lower right corners of Figure 12-17). This disappearance indicates that the rings are very thin. In fact, they are thought to be only about 10 meters thick (about 30 feet). In proportion to their diameter, Saturn’s rings are thousands of times thinner than the sheets of paper used to print this book.

The last edge-on presentation of Saturn’s rings of the twentieth century was in 1995–1996; the first two of the twenty-first century are in 2008–2009 and in 2025. From 1996 to 2008, we Earth observers see the “underside” of the rings (as in the image at the lower left corner of Figure 12-17); from 2009 until 2025, we see the “top” of the rings.

339

CONCEPT CHECK 12-8

What causes Saturn’s brilliant rings to be sometimes nearly invisible and at other times easily observable with the smallest of telescopes?