CHAPTER

13

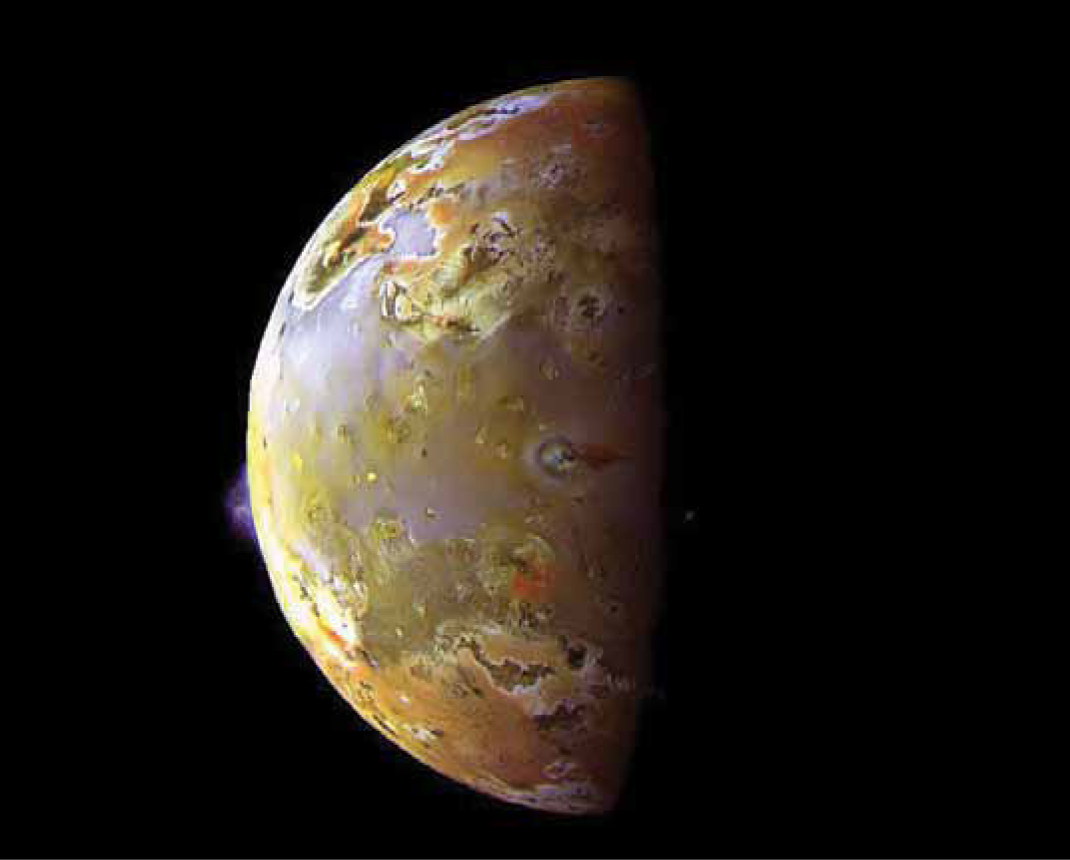

This is Jupiter’s moon Io, the most volcanically active body in the solar system. The faint plume on the left is an active volcano. This image was taken by the Galileo spacecraft.

351

Jupiter and Saturn's Satellites of Fire and Ice

LEARNING GOALS

By reading the sections of this chapter, you will learn

| 13–1 | What the Galilean satellites are and how they orbit Jupiter |

| 13–2 | The similarities and differences among the Galilean satellites |

| 13–3 | How the Galilean satellites formed |

| 13–4 | Why Io is the most volcanically active world in the solar system |

| 13–5 | How Io interacts with Jupiter’s magnetic field |

| 13–6 | The evidence that Europa may have an ocean beneath its surface |

| 13–7 | The kinds of geologic activity found on Ganymede and Callisto |

| 13–8 | The nature of Titan’s thick, hydrocarbon-rich atmosphere |

| 13–9 | Why most of Jupiter’s moons orbit in the “wrong” direction |

| 13–10 | What powers the volcanoes on Saturn’s icy moon Enceladus |

To many astronomers, the moons of Jupiter and Saturn are so unique and complex that they are best thought of as worlds. Io, shown in the above image, is the most geologically active world in the solar system. Its surface is covered with colorful sulfur compounds deposited by dozens of active volcanoes. Europa, another of Jupiter’s large satellites, has no volcanoes but does have a weirdly cracked surface of ice. Beneath Europa’s ice there is probably a worldwide ocean, within which there could possibly be small, single-celled organisms.

No less exotic is Saturn’s large satellite Titan, which is enveloped by a thick, nitrogen-rich atmosphere from which liquid hydrocarbons fall as rain and form massive lakes. Another moon of Saturn, Enceladus, shocks us with its ice-volcanoes, which Cassini has caught in the act of erupting. In this chapter we will explore these and other intriguing aspects of Jupiter and Saturn’s extensive collection of satellites.