PRIMARY SOURCES

- Edward Kemble, “San Francisco, 1848, First Drops of the Golden Shower,” Sacramento Daily Union, Saturday, March 22, 1873

- James K. Polk, Excerpt from State of the Union Address, December 5, 1848

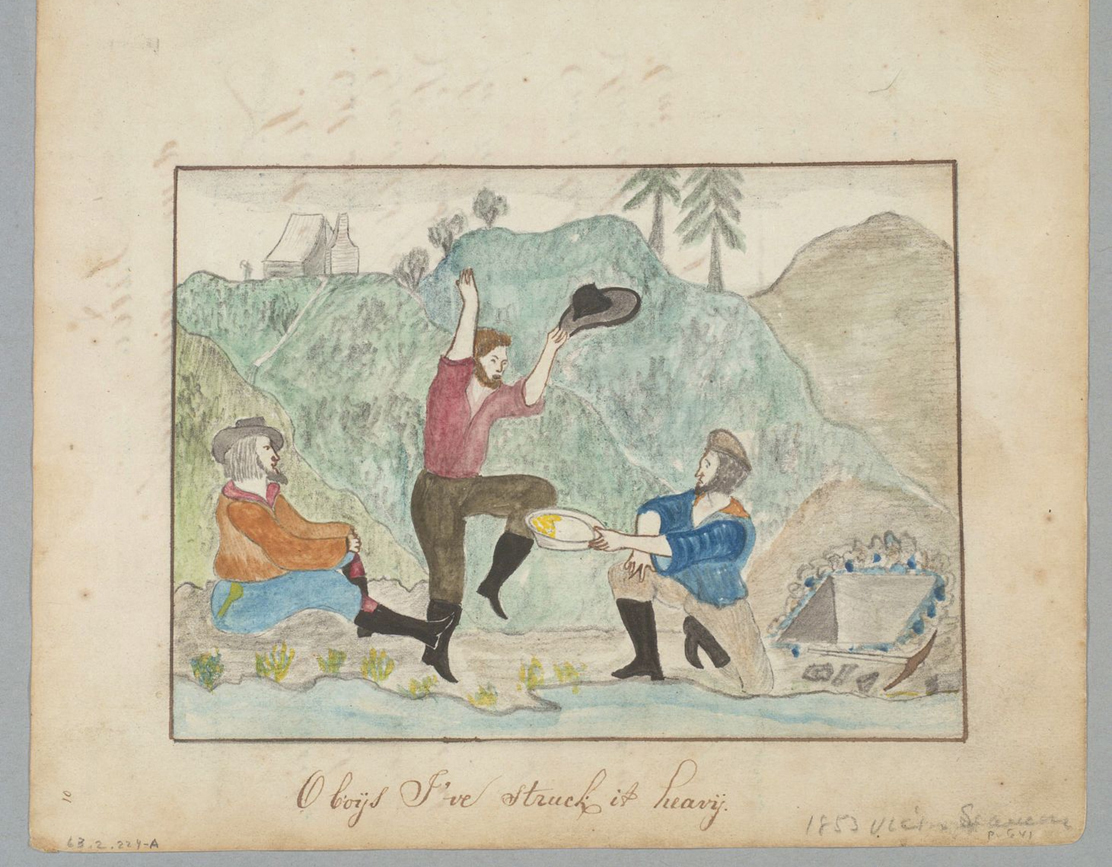

- “O Boys I’ve Struck It Heavy!” (sketch from miner’s journal), 1853

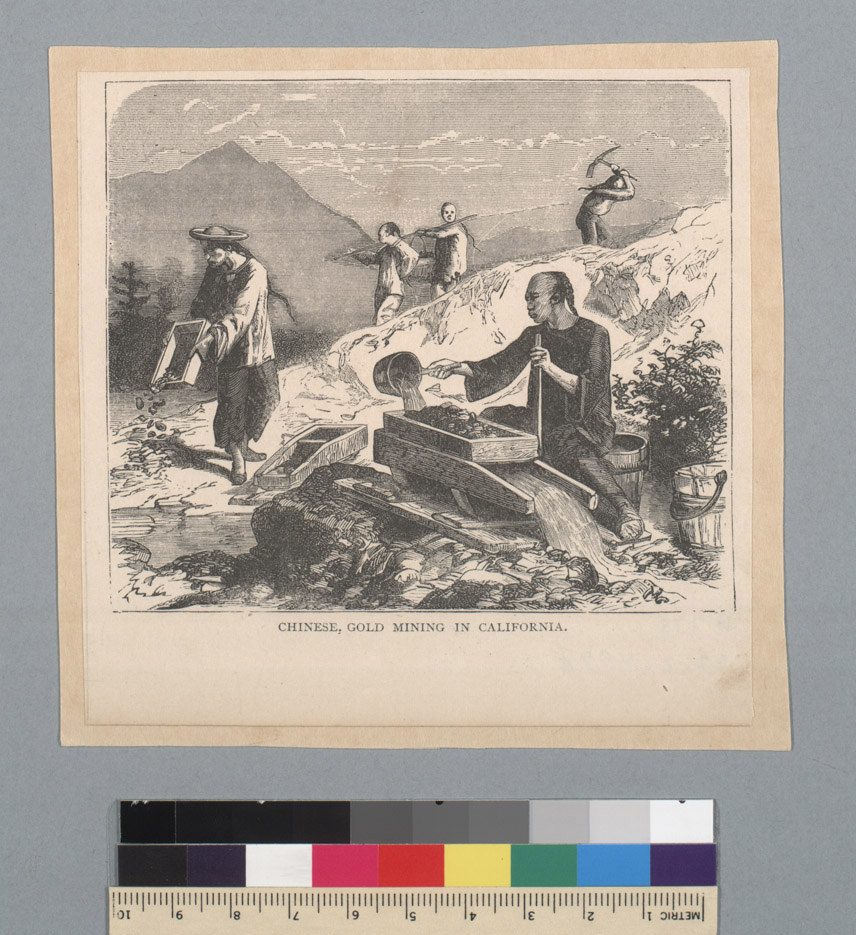

- “Chinese, Gold Mining in California”

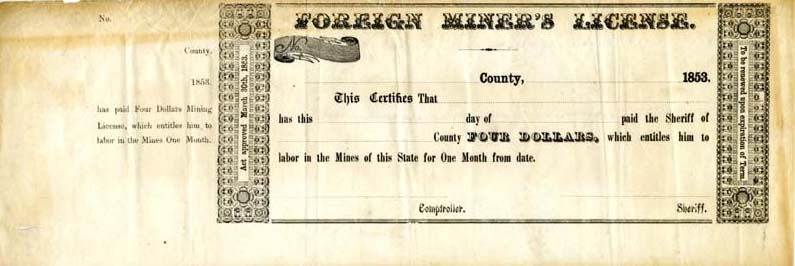

- Foreign Miners License Stub, 1853

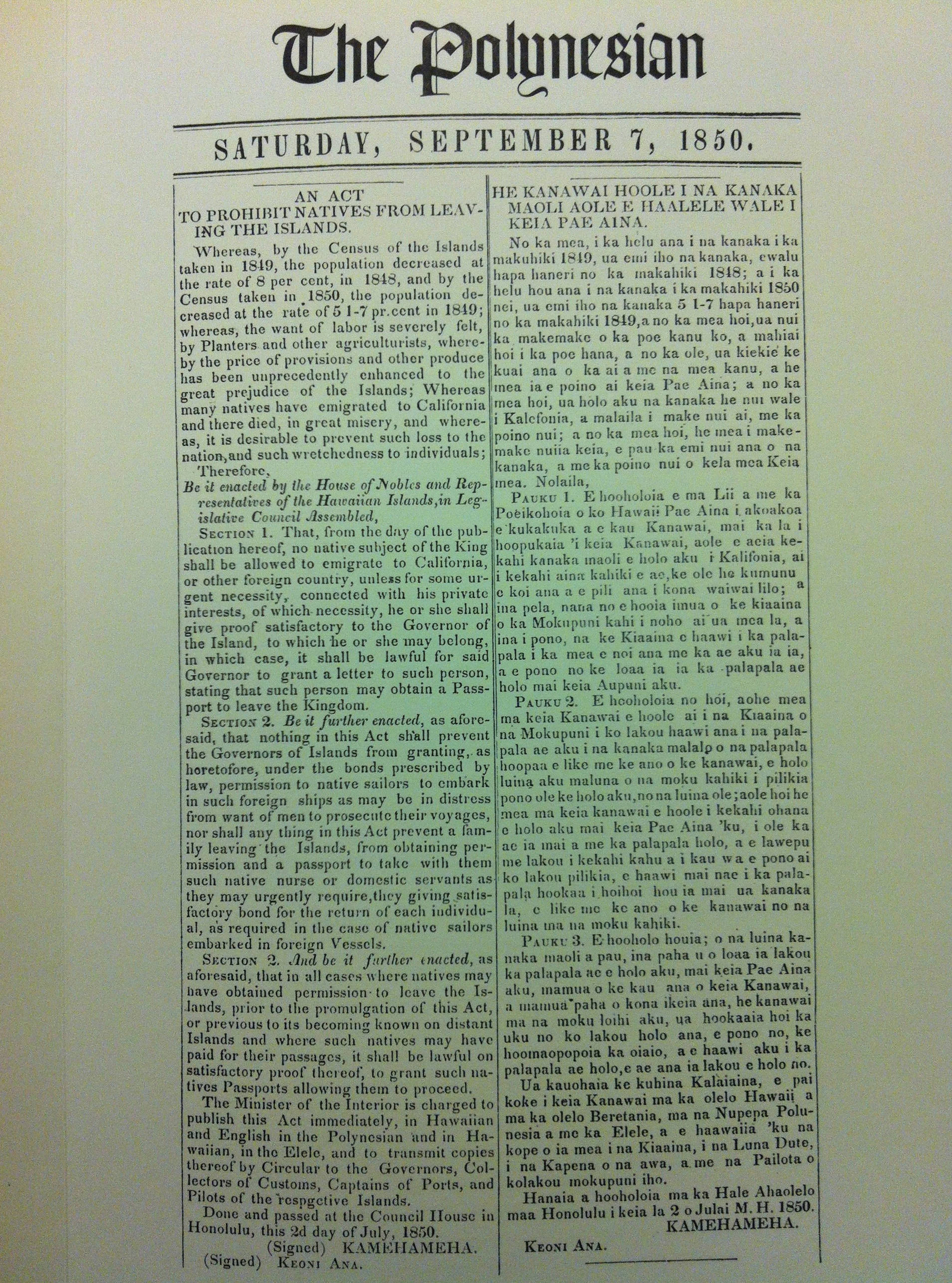

- “An Act to Prohibit Hawaiians from Emigrating to California,” The Polynesian, September 7, 1850 (attributed to King Kamehameha III)

- Excerpt from the Diary of Miner Alfred Doten, December 22, 1851 [[optional source]]

- Louise Clappe, Excerpt from the “Shirley Letters,” 1851 [[optional source]]

Edward Kemble, “San Francisco, 1848, First Drops of the Golden Shower,” Sacramento Daily Union, Saturday, March 22, 1873

Edward Kemble arrived in San Francisco in 1846 as a writer, opportunist, and part-time soldier. He would soon serve as editor of San Francisco’s first daily newspaper, the Alta California. Despite the initial rumors of gold in California, Kemble doubted the existence of major gold fields prior to James Marshall’s announced discovery in early 1848. He briefly tried his hand at gold-mining but, similar to most miners, was unrewarded for his efforts. Kemble had a tremendous career in California journalism over the next three decades. His “Reminiscences of Early San Francisco” appeared in a series of newspaper articles he published in the Sacramento Daily Union in 1873. He recalls the heady days of San Francisco prior to the gold discoveries, and he clearly describes his doubts about the existence of gold fields. This admission possibly reveals a level of honesty on Kemble’s part: rather than celebrating the gold rush that would soon commence, he shows that most people in San Francisco had no idea of the momentous change that soon shook their city.

Questions

-

Question

XrMcaoHPmS806eCpbDWo9gnD5Q68vGP4BLLV+00kQcz8btrWG2tFZ0Lf+t/fj4yZw4Pn9qCO+4sKJRE0gZ+uC+pJYJIbmhoi1VuT72mlIFCDmwO4oqhHc3uF1rrObFzSMnUuhg3MGUA6e670e64PugiRHijWawMBbNPgtw== -

Question

KNZWitTixdioj7TY+iJsZiwsB4nZEMXV4EFy93DQfGAEvPfXRlZINrpmVw+3MEYpsff/nBrzqofEWbQDNIcojYAXQtr1vmgHK/U1VV42c7T9WkwnA2POgzTy+y0= -

Question

XeC8XPmZ7rdiztwTJMHI7Zw9VBVgduhSVH1aF/8UpNvhFPDrZZI5W2GuY5EuBWDs2lP7bj8A13ue6VlyyRX1SmmXqEApYueCscey2pq7akwt3ltOWaZdhtr2PcqbZVJcl26N8/G8cwANRcXiaoUnzHvnPVG7JOTqo/nVqibsD/E5rgG7M8Sf2a9NtT4AAvJbvVe8L6iVNfAN/KFXP2YEwdzcktVcWlEsSySwyEdCzDWG9bxXsCgN1EgYPZQaQMWeXcUsAXTrJKhs54nV0H9wJQ==

I was standing in Howard & Mellus’s store, on Montgomery Street, near what is now Commercial Street, one day in March of this year, watching Sutter’s launch Sacramento, with its crew of Kanakas and Digger Indians, maneuver against an ebb-tide to make her landing off the foot of Clay street, about a stone’s throw from the beach at Montgomery street, and wondering if the two or three anxious-looking passengers in the stern were acquaintances, when the clerk of the store, who has been also watching the little schooner-rigged vessel, quietly remarked, “I suppose we shall hear if that story is true about the gold mine up in American.”

I have already said that the upper country had “turned loose” this Spring to hunt for silver, quicksilver, coal, iron, copper, sulphur, saltpeter, salt, black lead, and, in short, everything but gold (not excepting diamonds, which were reported to have been discovered in the Sonoma Valley), and that paragraphs in the two local papers about new mineral developments were beginning to grow stale and unprofitable. I was hoping for an item from the Sacramento to vary this monotony, and in the mind’s eye of a printer had measured the chances for about a “stick-full of matter,” needed to fill up the closing column and send the weekly Star to press. There had been woven into the dull gossip of the town that week a tiny thread of gold, caught from a rumor that floated like gossamer down from the upper country, but it was too thin and unsubstantial to make any sort of figure in the pattern, and had been rejected from the news material with which the Star loom with lofty discrimination supplied the market. Some native Californian, it was said, one of those hard riders who were continually posting about the country on their fast horses, had ridden across from Sutter’s embarcadero, through the “take cut-off,” to the ranches back of Benicia, and thence, crossing Carquinez Straits, had come through Livermore’s Pass to San Jose and San Francisco, all in two days from the point of starting (opposite the present site of Sacramento), and he had brought a report that some of Captain Sutter’s men had found gold on the American Fork.

further tidings about the gold mine up the American, the editor of the Star hoped it might bring an item about the number of acres Captain Sutter would sow in wheat this Spring, and thus foreshadow a more certain golden harvest in the Fall.

The passengers by the Sacramento—only four days from Sutter’s Fort—were strangers, and when they stepped ashore one of them asked where Captain Vioget lived, and being shown made haste in that direction, leaving the Star reporter to interview the others. They didn’t know anything about Captain Sutter’s sowing, or how many hides he would send down, or whether any parties were rendezvousing at the Fort for a start across the plains, or whether the prospects of an emigration from Oregon of the dissatisfied last year’s comers was as reported, or what was what, or which was which, for any practical purpose that the Star editor plied his questions; and the chanced of the “stickfull of matter” began to diminish to a bare possibility of a line or two, when of them said if we would “come up to the store” he would show us something.

And back to the store we all went. It is the strangest thing that I cannot remember this man’s name. He has been in the employ of Captain Sutter, but had come down on business of his own. He was black-eyed, bushy bearded, lank and nervous, and chewed tobacco as a school girl chews gum—as though the lower jaw was run by clock-work. Standing at the counter, he took out a greasy purse, and out of that produced a little rag, which he carefully opened, disclosing a few thin flakes of a dull yellow metal. “That there,” said he in an undertone, “is gold, and I know it, and know where it comes from, and there’s a plenty more in the same place, certain and sure!”

Too thin! What would have been the modern criticism on the specimens and on the stranger’s profession of faith in them? He was not in the least excited, and we set him down as acting a part. Other townspeople came into the store. And the little rag, with its lusterless bits of metal, was handed around. One said it was mica, and another that it was “fools’ gold”—he had “seen plenty of it in Oregon.” By and by the exhibitor was joined by his companion who had inquired the way to “old Vioget’s.” I afterwards learned that he had gone there to submit some specimens to the captain for “a test,” as he was reputed to have some skill in the analysis of minerals. Vioget’s opinion, if given at all, was not revealed. The party at the store separated without any very lively impression having been made on the lookers-on, and, if I remember aright, the Star went to press that night without an item concerning the gold mines.

These were the first drops of the approaching shower—the first flakes of that yellow snow-fall which was soon to change the face of the whole country—burying out of sight like the ashes which fell on Pompeii all traces of the former civilization, arresting human activity in its natural and healthy channels, and laying broad if not deep the foundations of a new order of things. The fair vestal of the Pacific was to receive in her embrace a new creating power, descending in a shower of gold, like the mythological deity of old. But like one of those foolish virgins, she still slumbered and slept. There was a considerable interval between the period when our eyes first beheld the new potentate whose scepter was to rule the land and the time when his throne was set up in our midst—a space of several weeks at least. During that interval the editor of the Star made a journey to the gold mines, the first quest of gold actually undertaken from San Francisco after the mines were discovered. But this memorable trip must form the subject of another chapter. Some notes which I have preserved of the business and social characteristics of San Francisco seem to fall appropriately into place here.

One of the grand events of this period was the introduction of steam navigation to the waters of the bay and rivers. Was it prophetic of the unhappy destiny which was to associate Yerba Buena Island (or Goat Island) in after years with the name of the unpopular railroad enterprise that the first trip by steam on these waters involved this island and resulted in failure. In October, 1847, the first steamboat was launched in San Francisco, having been brought into the bay in the hold of a Russian bark, consigned to Captain Leidesdorff, the Russian Consul. The little stranger came hitherward from the Russian settlements, on the Amoor river, and was originally destined for the inland waters of Alaska. Leidesdorff, though a foreigner, was imbued with the spirit of Yankee enterprise, and foresaw the greatness of California long in advance of his American brother merchants. He had the little steamboat put together, and endeavored to freight merchandize to different points on the bay. The Sitka, as she was called, actually made the trip to the present site of Sacramento, and was the pioneer of steam navigation on these waters. It would detract from her fame to place on record the time of her first trip. Let the waters of the bay, in which she foundered, a cable’s length from shore, be as the gentle wave of oblivion upon that page of her history. Her engine was too feeble and her hull too frail to wrestle with the northers that visited the bay that Winter. She was resurrected in the Spring, and her machinery having been taken out the little craft was fitted up as a schooner and called the Rainbow. Having made one or two successful trips to Sonoma and San Jose, she was dispatched to New Helvetia (Sacramento) in April. The first gold prospecting party that left San Francisco for the mines were passengers on that trip, and their adventures will be subsequently related.

The mercantile firms doing business in San Francisco at this time were Mellus & Howard, already mentioned, who advertised “cloths, cassimeres, pantaloons stuffs of various kinds, prints, brown and white cottons, ticking, tea, coffee, sugar, molasses, Columbia river flour, gin, aguadiente, ale, hollow ware, iron and steel, which they offer low for cash or hides,” etc. Shelly & Norris, corner of Clay and Kearny streets, Ward & Smith, Dickson & Hay, W. H. Davis & Co. dealt in a similar line of goods. Robert A. Parker at the “Adobe store” on the hill back of Portsmouth square, and Gelston & Co. (“New York store”) at the foot of Washington street were the latest comers, the former from Boston, and offered fresh and assorted stocks, including “novelties” in dry goods and fancy articles, such as had never been seen before in this market, and only 120 days from the States. The business of these mercantile houses cannot be said to have been extensive, although the local paper congratulates its readers on the brisk business done in April, the month in which the first ripple of excitement consequent on the discovery of gold was noticed. The editor says (April 22d, 1848): “The amount of sales by our merchants this week has exceeded twenty thousand dollars.”

The inland commerce of California was carried on by means of launches, or sloops and schooners of fifteen or twenty tons burthen, used chiefly for hide droghing purposes. The coast trade was confined to half a dozen brigs and schooners, running between San Francisco and the Columbia river, or the southern ports of Santa Cruz, Monterey, San Pedro and a Mexican port of two. There was a monthly arrival from the Sandwich Islands, and an occasional visitor from China. An eastern arrival was an event to make merry over. During December, 1847, and the three first months of 1848 there were fourteen arrivals of all kinds, two of which were from the United States. The others were from China and South American ports, the Sandwich Islands and coastwise traders. In the Fall of the year (about September) the whalers of the North Pacific dropped in to water and recruit supplies. Our merchants were ever casting hungry eyes in the direction of this whaling fleet, and fishing assiduously for these fishermen.

The historian of these times will find a barren page when he carries his search into the local annals after religious and educational items. The billiard-rooms of the two hotels provided the chief mental and moral pasturage of the average San Franciscan of those times for the entire seven days of the week. It is proper to state, however, that there was very little drunkenness and rarely a case of disorder. The town was governed almost without the aid of a constable. Gambling of course there was, as in every unreformed Mexican pueblo. The Town Council of 1848 made an effort to abolish it, but, some of its own members having been caught trying their hand in secret places at monte, the attempt was abandoned. The first school-house was erected during the Fall of 1847. It stood on the southwest corner of Portsmouth Square, occupying a part of the plaza itself. It was a little one-story frame building, and passed subsequently through a variety of uses. In the Winter of 1847–48 it was used for religious purposes. The first regularly organized Protestant congregation in San Francisco held its services there. K.

James K. Polk, Excerpt from State of the Union Address, December 5, 1848

Many Americans heard rumors of a gold strike in California prior to President James K. Polk’s announcement on December 5, 1848. This was especially true for citizens living in the major ports along the eastern seaboard that received trade and whaling vessels from the Pacific. President Polk’s message to Congress gave a government seal of approval to the veracity of these rumors. He had various motivations for announcing the news, including a desire to validate the spoils of war from the recently concluded conflict with Mexico. With his speech, Polk also urged citizens of the United States to head west and populate the new territory of California. The president’s wish was immediately answered by tens of thousands of Americans traveling to California by land and sea.

Questions

-

Question

SlJmjC9ebaBQPJm22ozKAK85lxhu+L8poZRPE9ZOTRQsrwAboi95N2URl8jcAp5nDyc6TW6WOOTDz8hkTkNoI7Nt4bkkDFBtyRwQko9XJX5SS2ktz0iGhfjXsDBcYX6t/BsNcLgFZmFqPYLjYEf5HzARY/y2wn9gISWiQ8v4gf31cO0F9PbbavAz3SWiWurqLuWILr8mJPN92Ki04wIfkw== -

Question

mOOqPLVoGQ/6pLbEh9NzHCj4g5GPUgcu38dKELjGf8qruPUxHJS9F6IRS84= -

Question

3gegjkmys/1/babR4MFGpYKfWt0eSpFaQP7M4tRspTjm00bQgdruJapTDLsJEK0EAX0eXMsPzxDKj9bZ8r2jd70/8s70Nfy4NDGFMRri+huZJD1C5ZC7/zRA8Vz6cPY1lDGlkUzKwK87Q0mk3RlytY06ZqBTv2M7iF9x5r3qjQmqsbhPAi7xgaKJpekO/PZUVrex8UH7Nda0rGctaxRM6Q==

James K. Polk, 1848 State of the Union Address, December 5, 1848. www.presidentialrhetoric.com/historicspeeches/polk/stateoftheunion1848.html

Upper California, irrespective of the vast mineral wealth recently developed there, holds at this day, in point of value and importance, to the rest of the Union the same relation that Louisiana did when that fine territory was acquired from France forty-five years ago. Extending nearly ten degrees of latitude along the Pacific, and embracing the only safe and commodious harbors on that coast for many hundred miles, with a temperate climate and an extensive interior of fertile lands, it is scarcely possible to estimate its wealth until it shall be brought under the government of our laws and its resources fully developed. From its position it must command the rich commerce of China, of Asia, of the islands of the Pacific, of western Mexico, of Central America, the South American States, and of the Russian possessions bordering on that ocean. A great emporium will doubtless speedily arise on the Californian coast which may be destined to rival in importance New Orleans itself. The depot of the vast commerce which must exist on the Pacific will probably be at some point on the Bay of San Francisco, and will occupy the same relation to the whole western coast of that ocean as New Orleans does to the valley of the Mississippi and the Gulf of Mexico. To this depot our numerous whale ships will resort with their cargoes to trade, refit, and obtain supplies. This of itself will largely contribute to build up a city, which would soon become the center of a great and rapidly increasing commerce. Situated on a safe harbor, sufficiently capacious for all the navies as well as the marine of the world, and convenient to excellent timber for shipbuilding, owned by the United States, it must become our great Western naval depot.

It was known that mines of the precious metals existed to a considerable extent in California at the time of its acquisition. Recent discoveries render it probable that these mines are more extensive and valuable than was anticipated. The accounts of the abundance of gold in that territory are of such an extraordinary character as would scarcely command belief were they not corroborated by the authentic reports of officers in the public service who have visited the mineral district and derived the facts which they detail from personal observation. Reluctant to credit the reports in general circulation as to the quantity of gold, the officer commanding our forces in California visited the mineral district in July last for the purpose of obtaining accurate information on the subject. His report to the War Department of the result of his examination and the facts obtained on the spot is herewith laid before Congress. When he visited the country there were about 4,000 persons engaged in collecting gold. There is every reason to believe that the number of persons so employed has since been augmented. The explorations already made warrant the belief that the supply is very large and that gold is found at various places in an extensive district of country.

Information received from officers of the Navy and other sources, though not so full and minute, confirms the accounts of the commander of our military force in California. It appears also from these reports that mines of quicksilver are found in the vicinity of the gold region. One of them is now being worked, and is believed to be among the most productive in the world.

The effects produced by the discovery of these rich mineral deposits and the success which has attended the labors of those who have resorted to them have produced a surprising change in the state of affairs in California. Labor commands a most exorbitant price, and all other pursuits but that of searching for the precious metals are abandoned. Nearly the whole of the male population of the country have gone to the gold districts. Ships arriving on the coast are deserted by their crews and their voyages suspended for want of sailors. Our commanding officer there entertains apprehensions that soldiers can not be kept in the public service without a large increase of pay. Desertions in his command have become frequent, and he recommends that those who shall withstand the strong temptation and remain faithful should be rewarded.

This abundance of gold and the all-engrossing pursuit of it have already caused in California an unprecedented rise in the price of all the necessaries of life.

That we may the more speedily and fully avail ourselves of the undeveloped wealth of these mines, it is deemed of vast importance that a branch of the Mint of the United States be authorized to be established at your present session in California. Among other signal advantages which would result from such an establishment would be that of raising the gold to its par value in that territory. A branch mint of the United States at the great commercial depot on the west coast would convert into our own coin not only the gold derived from our own rich mines, but also the bullion and specie which our commerce may bring from the whole west coast of Central and South America. The west coast of America and the adjacent interior embrace the richest and best mines of Mexico, New Granada, Central America, Chili, and Peru. The bullion and specie drawn from these countries, and especially from those of western Mexico and Peru, to an amount in value of many millions of dollars, are now annually diverted and carried by the ships of Great Britain to her own ports, to be recoined or used to sustain her national bank, and thus contribute to increase her ability to command so much of the commerce of the world. If a branch mint be established at the great commercial point upon that coast, a vast amount of bullion and specie would flow thither to be recoined, and pass thence to New Orleans, New York, and other Atlantic cities. The amount of our constitutional currency at home would be greatly increased, while its circulation abroad would be promoted. It is well known to our merchants trading to China and the west coast of America that great inconvenience and loss are experienced from the fact that our coins are not current at their par value in those countries.

The powers of Europe, far removed from the west coast of America by the Atlantic Ocean, which intervenes, and by a tedious and dangerous navigation around the southern cape of the continent of America, can never successfully compete with the United States in the rich and extensive commerce which is opened to us at so much less cost by the acquisition of California.

The vast importance and commercial advantages of California have heretofore remained undeveloped by the Government of the country of which it constituted a part. Now that this fine province is a part of our country, all the States of the Union, some more immediately and directly than others, are deeply interested in the speedy development of its wealth and resources. No section of our country is more interested or will be more benefited than the commercial, navigating, and manufacturing interests of the Eastern States. Our planting and farming interests in every part of the Union will be greatly benefited by it. As our commerce and navigation are enlarged and extended, our exports of agricultural products and of manufactures will be increased, and in the new markets thus opened they can not fail to command remunerating and profitable prices.

“O Boys I’ve Struck It Heavy!” (sketch from miner’s journal), 1853

Most of the people who descended on California during the gold rush shared one ambition: to strike it rich. Many of them imagined the foothills and streams were filled with gold so plentiful that they could pick it up by hand. They dreamed of gold by night and wrote about it in their journals. They valued the companionship of their fellow miners, some of whom were their best friends and relatives from back home. They hoped to work in small groups like a family, find some easy gold, and return home wealthy and world-wise. Most miners were sorely disappointed when none of these dreams came true. The miner who worked in a small group of comrades (certainly possible in 1849) quickly gave way to well-funded mining companies that employed diverse and large groups of laborers.

Questions

-

Question

Be7ydo1ROskXaM1RovNhiwpbJUoDPZUqAanN7HfqLERTgkHtsxf7uoaQKdalYuRXwN9J4fI1USlPyFQxyduJBaRrJzYbCJJoKMv4fF+pkaHvoR8/vrIOpcnXP6+hlb/SyK7cAQ9GmdZ4gPLYKKPgGEx5eAB8ayqCuj1lkaWOaEY/oa+LD+TFdp684WhPPGoH4jb8zj0difv3ZA+XRNGY7H+XO0G/dOKrZnNZ1q4Nl4VxE7TpJjZINLbPrdx59whV -

Question

KswSWcbKBPm7t/5KU4p14hRtrI5bJCdENS9VOzNEp6s+rAfbQxAYZ1gNAovoLuQnqaJ8oHVoVzWVliGSqeTv2OiVQW9OgeYJcIwmnrgjLoI= -

Question

QqYiED9TCgkliDA3hhbNIIcYICjqGV1A/jkMEOOwcJcJmw7wnbNGMgt1sHS6RzuZU8WIFGpOBKsrkQZrutEU9udJBCfk4IentJrKqjwPPwfold+RjflRr1gQ+8mDao6N

“Chinese, Gold Mining in California” (image from magazine; author and date unknown)

Few issues were more volatile in late-nineteenth-century California than Chinese immigration and labor. Most “white” Californians—and “white” was a conveniently flexible term for those who embraced it—deeply resented Chinese immigrants for their perceived cultural difference and economic threat to “white” workers. The first groups of Chinese miners arrived from across the Pacific Ocean in 1849. Some Chinese miners labored as “contracted” workers, individuals who paid off their transportation costs through a certain term of manual labor. But by the early 1850s, most Chinese immigrants arrived and worked under their own free will—either for wages from a mining company, or in small groups of their fellow countrymen. White racial animosity encouraged them to avoid American and European miners, so they often worked the claims already rejected by other groups.

Questions

-

Question

eqrDjS7agDhfGzufEePGWG6MMSeFeg1lftHSfA3uQ2CvVMto1ugmIK7s1iGj3EVjn5DMb0d+gr+DhJFW2GQFl7G/9P15iicE -

Question

dD7D71GuMi6dgr/VPiWa6xUdwL6NeIPWx8Yy7Wo369IAuFOVU743mV+QPC/MX6YSqeDL2ALPQbTnzlQ6tjku5OU3LllfDsG1OXBEm0rynIvnr5TjlbqaTvYvi3nU99cWoEy5H2QSDg2fu1uGYyz9G4zIF0xri6u6Le92bCH1+JTW5yp8Ep0ooSfzo97ZBdQUQlMMrA/etl42dWgNVCuryw== -

Question

j7s1stOuij8SBwCnzvetNQ7x/uZDc3GrU9E+SQod77zmeVUq0LLI72d7plZ25UINk+j/UA5/tBL2ZDudEr+3EhWf1xhrLPxZg6c/U5tRJSX16C4o

Foreign Miners License Stub, 1853

By 1852, almost 20,000 Chinese immigrants had arrived in California. They represented only one part of the state’s cultural diversity, but they were easily the most notable and despised portion of that diversity. Historian Alexander Saxton described Chinese immigrants as the “indispensable enemy”; in other words, an easy and necessary target for racial hatred. Efforts to restrict “foreign” miners in California began in 1850, with a twenty-dollar-per-month tax on anyone construed to be a foreigner (this applied primarily to Mexicans and Latin Americans). Various immigrant groups protested this tax. On March 30, 1853, the California state legislature passed a new “license” tax of four dollars per month on miners who were not citizens of the United States—and everyone knew this law applied specifically to Chinese immigrants. The enforcement of this law was often carried out by groups of whites with little legal authority from the state of California. Chinese miners had to receive a new “license” each month or face prosecution.

Questions

-

Question

vSIo2tA6HXwaeyStPp8UKWh7Eemc0N6FlRky8CwnaLP5IkHuTsVCOKYQY1TFVmtSk5hfqhZTzQOv95l+j16SJxA1qcp7eSZ3DHRJViLuYYvbZdqtCOVNjiX6i/T0mRVoL1J9QQ== -

Question

1ZE+ZDMo3baSaL+og1TPhGgou3kW+EZDI0M23aZqTkhir2RRtipE3avpukWWKRzNDzigNY78jszlOiLzgeTGBp08s3M= -

Question

6lKVMD8fTODQL52ykLsTRTZxIplEo0IZAe6Yyy+eLkWH2u1f40oi66JIn6LBoQOvOefcajb99CgR01ASTrMkE7XAWE4cwvsK

“An Act to Prohibit Hawaiians from Emigrating to California,” The Polynesian, September 7, 1850 (attributed to King Kamehameha III)

Indigenous Hawaiians arrived in California well before the gold rush on European and American sailing vessels. In fact, they were essential laborers on these ships—a role that went back to the early 1800s. Diseases introduced by foreigners had decimated the native Hawaiian population, beginning with the earliest “discovery” voyage of Captain James Cook in 1778. The Hawaiian population continued to decline owing to shipboard workers’ death rate on trans-Pacific voyages. For this reason, some elite Hawaiians feared that the California gold rush would only increase the exodus of Hawaiian commoners from the islands. In 1850, King Kamehameha III authored this “Act to Prohibit Hawaiians from Emigrating to California.” It was largely unenforceable, given the number of foreign ships that arrived and departed from the Hawaiian Islands. But it nonetheless shows a deep concern for the out-migration of Hawaiians during this period of severe native population decline.

Questions

-

Question

JoDwpRXDBa2ZA4eEjeonirswe0Egi27SZq8tSMSDe9i3x3xoZhGhpTRxTdD2k2eeYGul8WVpW/9DmXWzo2wJTpVbDB361rD9fguwVS3EW4ORTPWuh02ZZnrrQdkgHsNuIOFiD22bKefNrK8llMTUL/nNWeZe8lRx6by/VhXuXy9SM7IGkfVB5gfSNyOMYwzbyESgfrt5qieYvIAP0MEdVjEk8yLGKevcMa9SmpYcKkI= -

Question

Qq4itNqX0AHVmKyqf5v3RpHLGXJoqKNh07te190KSlbaVv0bk6kZRGQAEFqUD+Q19F2LGju67zsvvOf9+Z0aj1ocDdJBiZlgjmKyC40RR2DHRs/VK+11pZPchdL0ayJoPL/VXrCIYqA= -

Question

4ZuM+buqoEFjq8TKPfZ5o+a4U8hqi4HnvzDjN2xiSXMJfJSfBVcz+Dq4/loyxXlPtnrY+ly8rq7anMT5fFSNQ+MULLly1nxZYFd+wh190yMFKaP2afETRLNO0r5mAMEO

Excerpt from the Diary of Miner Alfred Doten, December 22, 1851

In the spring of 1849, Alfred Doten joined a group of mostly young men in Massachusetts, and together they set sail for California. Like many similar groups embarking for the gold rush, they gave themselves a name (the “Pilgrim Mining Company”) and established rules of behavior for their journey, such as temperance and observance of the Sabbath. Their ship, the Yeoman, arrived in San Francisco in October 1849, and everyone traveled to the Sierra gold country, where they had high expectations of success. Doten would never strike it rich; in fact, he had to scrape a hard living as a miner and eventually pursued an unstable career in journalism in Nevada and California. In the following diary entry, he describes his participation in a mob of Anglo miners who track down and put on trial two young men from Mexico accused of murder. “Justice”—vigilante and otherwise—moved quickly in gold rush California, especially when it involved accused men and women who were not “white” Americans.

Questions

-

Question

/AAm6FUkxDj1sMwPtU0frcmyAaxVX2jl79J2/HB42U5BwBefF43MWFXmdpq1FH9BEBOvfBG4aS9bkQe7Jl9fCZ7BOMn992tRblrpVbIGuoTJFWXFg/qXzU2jVW8rErHUNyXV/jCGjQ23nXD/WYHXuJrZJArcwIzuwU3s0sDqhoYycdrdBpVobqLBuMRb0kvyUCnjpSGbN1LkVqNM -

Question

LfcX7jD9DDTErIfnlNYQAjEknfI1x/IDfof31owmPaEgwPuislvoQx2JfTK3suBQaPJF4TKD6JDYi8y8rzEJ8aYQSXjJCVslJ/+fOrrJwvceBxWWchNDemJfZeX6NB3YpXoIHK03OOuqWx/4vcOP9dep/eWXXfbs93EUd9WaT1NDLi63

From The Journals of Alfred Doten, 1849-1903, edited by Walter Van Tilburg Clark. Copyright ©1973 by University of Nevada Press. All rights reserved. Reproduced with the permission of the University of the Nevada Press.

Dec 22.—Rainy––Today is “Forefathers day” at home, and there it is celebrated in the most pleasing manner and the evening and night passes off with balls, parties &c, but here we celebrated it in a far different manner––Just after daylight I went down to my camp & took a cup of coffee, after which I went immediately back again, where I found none but Dr Quimby had arrived from below on the gulsh and nothing was said about starting in pursuit of the Mexican rascals––I had great difficulty in raising a small crowd to go with me over to the Mexican camp on the north gulsh to search for them, but after arguing the case and talking on the subject some time, and daring two men of them to go with me, I managed to get some half a dozen to go with me––We went over there and searched all the camps till we came to one where we found a Mexican lying rolled up in his blankets––We looked at him very suspiciously, but he said he had bad fever and was very sick, and as neither Chinn, Everbeck, Dixon or Flynn, who were with me, could swear to his identity, we thought it a pity to trouble a sick man, therefore we did not look to see if he had a ball in his hip, although we afterwards found that he was the rascal himself––The whole outrage was committed so quick, and, as the lights were blown out immediately, there was no chance to examine countenances closely––but Chinn had put a mark on him that was not easily got rid of. While we were searching the camps, a man came out of a tent just on the outskirts on the village and fired a pistol up the gulsh, which we rightly judged was a signal to one or two camps a little farther up the gulsh––We immediately went up there and came to the tent of three Mexican acquaintances of ours, two of them brothers by the name of Lopez. They sat on the bed playing cards but as they assured us that the rascals were not there, we did not search their camp but returned to Guadalupe’s tent––We had been there but a short time when a boy told us of an old Mexican who knew where the rascals were hid. We went to him and by threatening him with instant death we forced him to go with us, after tying his hands and leading him with string. This time we mustered a pretty strong crowd, well armed, and went back to the North gulsh. He told us that one of them was hid under the bed in Lopez’s camp. We went there and found them sitting on the bed playing cards, with the blanket hanging over the edge, just as they were before, and on looking under the bed we found the villain there, stowed away as snug as a bug. We ordered him out and identified him as the one that Alex shoved away from the bar and the worst of the rascals. He trembled from head to foot as we tied his hands, still protesting his entire ignorance of the affair––We escorted him down to the old rish gulsh and seeing him stowed safely away in Perry’s store and securely guarded, we started back for the other one who was wounded in the hip. At Perry’s we heard that Alex had just died. He died about 10 o’clock AM. He was sensible to the last and died without a struggle, sinking calmly into his last long sleep––We went back to the North gulsh and found our good friend the Mexican who pretended to have a bad fever, still lying where he was, and soon found that his principal ailment was an impediment in his locomotion occasioned by a ball in his hip––He knew that it was about a gone case with him. He limped very bad, but we treated him to a ride on a jackass, and soon had the pair of the murderers sitting under a strong guard in Perry’s store––Early this morning Mr Crawford started post haste for Columbia bar on the Mokelumne, about 15 miles off, for Dave Keller and some other friends of Alex. About 2 PM the boys brought old uncle Jimmy down to his camp just as they were bringing down the corpse of poor Alex, Dave Keller arrived, having outrode his companions. Just as he sprang from his horse, someone told him that Alex was dead and the murderers were taken and were in Perry’s store. Dave gave a glance at the party who were bringing the corpse of his dear friend Alex––that look was enough. He turned pale as a ghost and drawing his revolver, cocked it, and rushed like a madman towards Perry’s store. We saw him coming and his murderous intent depicted on his countenance and by all of us crowding together and preventing him from entering, we saved the lives of the murderers for the present. But such a scene as this. Oh my God may I never look upon such another––Poor Dave––he begged us, prayed us, to let him shoot them. “Oh, let me kill them with my own hands,” “Alex was my last partner and I loved him as a brother”––“He fought for his country! You are all enjoying the fruits of his labours and now you will let his murderers get away”––“Oh! ’twas just a year ago last evening that Figot was shot, just about the same hour, and on just such a night, and they let his murderers get away.” (He alluded to another friend of his by the name of William Figot, who was killed over at Winter’s bar at this time last year––) Poor Dave. When he found we would not let him shoot the prisoners, he dropped his pistol and laying his head on Chinn’s shoulder and cried like a child. All he could say was “Oh Jake! Alex! Alex! Alex!” The scene was indeed affecting and from very sympathy I cried too and many a rough hardy miner turned away from the scene to wipe away their tears which came rolling down their bronzed and manly cheeks. We assured him that these murderers were safely in our hands and could never leave the store alive unless they were taken out to be hung. We immediately chose a jury of twelve men (I was one of the jury) and after examining some half dozen witnesses, who all swore point blank as to the identity of the prisoners, and gave the most incontestible evidence as to these being the murderers, the jury cried out. “enough, this is evidence enough.” We had not brought in more than half of our evidence, but as this was considered enough, the jury retired––About this time the rest of those friends of Alex who started from Columbia bar and whom Dave Keller left behind, arrived. They were fierce for blood, but as the jury had just retired, they committed no violence, although they said it mattered not what the jury said, the prisoners must die before morning––The jury were out but about 15 minutes. We agreed that according to the evidence the prisoners were guilty of willful murder and should be hung, and as the prisoners would not be allowed to live till morning, they should be hung immediately––We brought in this verdict about 7 o’clock in the evening––The evening was dark and stormy and the fierce wind roaring among the tall pines seemed to howl the death song of the two murderers––We asked them what they had to say against the verdict. They said they were not guilty, and one of them swore that he was ignorant of the whole affair, although he was the very one whom Alex pushed from the bar––Some of the people wished to have them put up as a mark to shoot at, others wanted to burn them, but the jury had decided that they should be hung. We formed a guard of 20 men, well armed men, and taking Bill Fenton’s riatta from his horse and making a hangman’s knot at each end of it we put it about their necks and led them forth to execution under escort of the guard. The one who was shot in the thigh hobbled badly and finally gave out and two of the guard had to carry him. A candle put in an old tin cracker case served us for a lantern––We took them just across the gulsh opposite to the town, and throwing the bite of the riatta over the limb of an old pine tree, we ran them both up together, but one of them being very heavy, his end of the rope broke and he dropped down. His hands were tied but his feet were not but as soon as he touched the ground more than a dozen sprang upon him. He got on his knees and cried “pardon!! Pardon!!! Santiago,” but he was in another moment swinging by the rope again. This time he did not break down, but hung there––He was the one whom Alex pushed; he was a desperate villain and a noted highway robber and murderer in Mexico. Both he and his companion were hated and feared by the other Mexicans here, who were glad when they heard that they were hung––They made no confession at all and when time was given to them to say their prayers or to leave word for their friends, if they had any, they said that they didn’t wish to do anything of the kind, and so as there is no priest here, they died “without benefit of the clergy.” After they had hung about half an hour, we left them to swing in the wind till morning and we all dispersed––I slept at my camp with James Flynn and John (a Mexican boy) for company––The wounded one hardly moved after he was run up and seemed to die easy, but the other one writhed about and seemed to die hard––The taking of the murderers, the trial and execution was carried on in the most quiet and orderly manner throughout––The night was dark and fearful and together with the howling and roaring of the wind through the tall pines and the warring of the elements rendered the scene awful and terrific in the extreme and on that will never be effaced from the memory of those who witnessed it––

Louise Clappe, Excerpt from the “Shirley Letters,” 1851

Louise Amelia Knapp Smith Clappe sailed from Massachusetts to California in 1849. She and her husband went to the gold country and briefly settled in Marysville, where she was given the opportunity to write for The Marysville Herald about her travel adventures. She assumed the name “Shirley” as a pseudonym for her public writings. She also penned a series of twenty-three letters to her sister Mary Jane in Massachusetts in 1851 and 1852, and these subsequently became known as the “Shirley Letters,” which describe mining life in the gold region of California. The letters provide a vivid (if somewhat exaggerated) account of the “diggings,” the surrounding landscape, and the bustle of mining life.

Questions

-

Question

iyUcCOc1/W0FLZBe6QfYbXDAKhGsdHM3BOYpq1NCxgzivDY8+HcQ5vRVEjff/bMMJJZcBRUpVUAAgwG1IzPCyN5ar7k8pMYowyq3cTEI7j0wGL+FQxvB3JnlEdJRE+I6 -

Question

0oHguwqa5XbBuBcqmrNu+m/BFrBW0LQt8/nt7neMRHFAEDF0mhPk8xONLkjGemOgrfcsaAungWuFwYc18B0Fo160k4cb3Hv0DNBqlsQZ23xJYlPMG+tlrWm5a02dq1Y4zTMX16N3K0v1c2K7yqIAlg2uAjdQb7eP+0gnkBGXTKeUfu4LGq072A==

Dame Shirley, The Shirley Letters from the California Mines, 1851–52. New York: Knopf, 1949, 1–14.

Letter the First

Part One

The Journey to Rich Bar

Rich Bar, East Branch of the North Fork of Feather River,

September 13, 1851.

I can easily imagine, dear M. [sister], the look of large wonder which gleams from your astonished eyes when they fall upon the date of this letter. I can figure to myself your whole surprised attitude as you exclaim, “What, in the name of all that is restless, has sent ‘Dame Shirley’ to Rich Bar? How did such a shivering, frail, home-loving little thistle ever float safely to that far-away spot, and take root so kindly, as it evidently has, in that barbarous soil? Where, in this living, breathing world of ours, lieth that same Rich Bar, which, sooth to say, hath a most taking name? And, for pity’s sake, how does the poor little fool expect to amuse herself there?”

Patience, sister of mine. Your curiosity is truly laudable, and I trust that before you read the postscript of this epistle it will be fully and completely relieved. And, first, I will merely observe, en passant, reserving a full description of its discovery for a future letter, that said Bar forms a part of a mining settlement situated on the East Branch of the North Fork of Feather River, “away off up in the mountains,” as our “little Faresoul” would say, at almost the highest point where, as yet, gold has been discovered, and indeed within fifty miles of the summit of the Sierra Nevada itself. So much, at present, for our local, while I proceed to tell you of the propitious—or unpropitious, as the result will prove—winds which blew us hitherward.

You already know that F., after suffering for an entire year with fever and ague, and bilious, remittent, and intermittent fevers,—this delightful list varied by an occasional attack of jaundice,—was advised, as a dernier ressort, to go into the mountains. A friend, who had just returned from the place, suggested Rich Bar as the terminus of his health-seeking journey, not only on account of the extreme purity of the atmosphere, but because there were more than a thousand people there already, and but one physician, and as his strength increased, he might find in that vicinity a favorable opening for the practice of his profession, which, as the health of his purse was almost as feeble as that of his body, was not a bad idea.

F. was just recovering from a brain-fever when he concluded to go to the mines; but, in spite of his excessive debility, which rendered him liable to chills at any hour of the day or night, he started on the seventh day of June—mounted on a mule, and accompanied by a jackass to carry his baggage, and a friend who kindly volunteered to assist him in spending his money—for this wildly beautiful spot. F. was compelled by sickness to stop several days on the road. He suffered intensely, the trail for many miles being covered to the depth of twelve feet with snow, although it was almost midsummer when he passed over it. He arrived at Rich Bar the latter part of June, and found the revivifying effect of its bracing atmosphere far surpassing his most sanguine hopes. He soon built himself an office, which was a perfect marvel to the miners, from its superior elegance. It is the only one on the Bar, and I intend to visit it in a day or two, when I will give you a description of its architectural splendors. It will perhaps enlighten you as to one peculiarity of a newly discovered mining district, when I inform you that although there were but two or three physicians at Rich Bar when my husband arrived, in less than three weeks there were twenty-nine who had chosen this place for the express purpose of practicing their profession.

Finding his health so almost miraculously improved, F. concluded, should I approve the plan, to spend the winter in the mountains. I had teased him to let me accompany him when he left in June, but he had at that time refused, not daring to subject me to inconveniences, of the extent of which he was himself ignorant. When the letter disclosing his plans for the winter reached me at San Francisco, I was perfectly enchanted. You know that I am a regular nomad in my passion for wandering. Of course my numerous acquaintances in San Francisco raised one universal shout of disapprobation. Some said that I ought to be put into a straitjacket, for I was undoubtedly mad to think of such a thing. Some said that I should never get there alive, and if I did, would not stay a month; that it was ever my lot to be victimized in, and commenced my journey in earnest. I was the only passenger. For thirty miles the road passed through as beautiful a country as I had ever seen. Dotted here and there with the California oak, it reminded me of the peaceful apple-orchards and smiling river-meadows of dear old New England. As a frame to the graceful picture, on one side rose the Buttes, that group of hills so piquant and saucy, and on the other, tossing to heaven the everlasting whiteness of their snow-wreathed foreheads, stood, sublime in their very monotony, the summits of the glorious Sierra Nevada.

We passed one place where a number of Indian women were gathering flower-seeds, which, mixed with pounded acorns and grasshoppers, form the bread of these miserable people. The idea, and the really ingenious mode of carrying it out, struck me as so singular, that I cannot forbear attempting a description. These poor creatures were entirely naked, with the exception of a quantity of grass bound round the waist, and covering the thighs midway to the knees, perhaps. Each one carried two brown baskets, which, I have since been told, are made of a species of osier, woven with a neatness which is absolutely marvelous, when one considers that they are the handiwork of such degraded wretches. Shaped like a cone, they are about six feet in circumference at the opening, and I should judge them to be nearly three feet in depth. It is evident, by the grace and care with which they handle them, that they are exceedingly light. It is possible that my description may be inaccurate, for I have never read any account of them, and merely give my own impressions as they were received while the wagon rolled rapidly by the spot at which the women were at work. One of these queer baskets is suspended from the back, and is kept in place by a thong of leather passing across the forehead. The other they carry in the right hand and wave over the flower-seeds, first to the right, and back again to the left, alternately, as they walk slowly along, with a motion as regular and monotonous as that of a mower. When they have collected a handful of the seeds, they pour them into the basket behind, and continue this work until they have filled the latter with their strange harvest. The seeds thus gathered are carried to their rancherías, and stowed away with great care for winter use. It was, to me, very interesting to watch their regular motion, they seemed so exactly to keep time with one another; and with their dark shining skins, beautiful limbs, and lithe forms, they were by no means the least picturesque feature of the landscape.

Ten miles this side of Bidwell’s Bar, the road, hitherto so smooth and level, became stony and hilly. For more than a mile we drove along the edge of a precipice, and so near, that it seemed to me, should the horses deviate a hairbreadth from their usual track, we must be dashed into eternity. Wonderful to relate, I did not “Oh!” nor “Ah!” nor shriek once, but remained crouched in the back of the wagon, as silent as death. When we were again in safety, the driver exclaimed, in the classic patois of New England, “Wall, I guess yer the fust woman that ever rode over that are hill without hollering.” He evidently did not know that it was the intensity of my fear that kept me so still.

Soon Table Mountain became visible, extended like an immense dining-board for the giants, its summit a perfectly straight line penciled for more than a league against the glowing sky. And now we found ourselves among the Red Hills, which look like an ascending sea of crimson waves, each crest foaming higher and higher as we creep among them, until we drop down suddenly into the pretty little valley called Bidwell's Bar.

I arrived there at three o'clock in the evening, when I found F. in much better health than when he left Marysville. As there was nothing to sleep in but a tent, and nothing to sleep on but the ground, and the air was black with the fleas hopping about in every direction, we concluded to ride forward to the Berry Creek House, a ranch ten miles farther on our way, where we proposed to pass the night.

Project Questions

- Which of these documents best demonstrates the larger Pacific Ocean context of the California gold rush?

- In what ways do the documents illustrate both the strong optimism that attended the gold rush and the fears and conflicts of those who went to California?

- Compare the perspectives of two heads of nations: James K. Polk in 1848 and King Kamehameha III in 1850.

Project Assignments

- All of these documents offer a different view or experience of the California gold rush. To varying degrees, they also demonstrate how the gold rush held meaning on different geographic “scales” of history: the local story of miners on a river, the national story of a U.S. president announcing a major gold strike, and the trans-Pacific story of Chinese miners and Hawaiian monarchs. Construct a series of fictional journal entries in which your character/writer reflects on individuals or events that demonstrate these different scales of history.

- How would you use digital media to represent the California gold rush? Using the available online resources (maps, drawings, photographs, newspaper headlines), prepare a digital presentation for your classmates. Your presentation should demonstrate the historical evolution of gold rush California during the first five years (1848–53).

Additional Resources for Research

Angela Hawk, “Going ‘Mad’ in Gold Country: Migrant Populations and the Problem of Containment in Pacific Mining Boom Regions,” Pacific Historical Review 80 (February 2011): 64–96.

In this prize-winning article, historian Angela Hawk analyzes the relationship between insanity and gold rushes in California and later in British Columbia and Australia. Of the many young men who left home and hearth to strike it rich in the gold fields, some showed signs of mental instability, chronic drunkenness, and violent behavior. “Gold Fever,” as it was sometimes called, seemed to affect many young men in the heady days of the gold rush. In response to this problem, the California legislature created the state’s first insane asylum in Stockton in 1853. Hawk describes in particular the experiences of a young man known as Scotty.

David Igler, “Alta California, the Pacific, and International Commerce before the Gold Rush,” in William Deverell and David Igler, eds., A Companion to California History, Wiley-Blackwell, 2008), 116–26.

In this essay, historian David Igler argues that California was a destination for international trade vessels long before the gold rush. California was one of many regions in the Pacific Ocean that witnessed increased trade in the early nineteenth century. Other common trade centers were Peru; Hawaii; Canton, China; and the northwest coast of North America. Drawing on a database of almost 1,000 European and American ships that entered the Pacific prior to the gold rush, Igler’s work studies the vessels’ destinations, cargos, and nationalities. The California gold rush sparked a new era of trade in the Pacific Ocean, and California became the primary destination of migrants in the 1850s.

The public and private archives of California are filled with primary source material related to the gold rush. These records include published and unpublished documents, such as early newspapers, court records, memoirs, diaries, photographs, sketches, maps, and letters. A great deal of material can be found online, especially at research institution Web sites like www.calisphere.universityofcalifornia.edu.

Summative Quiz